Contents

Guide

A Great Gray Owl comes in for the kill. It can hear and accurately target a vole moving under up to 2 feet (61 cm) of snow.

Shutterstock

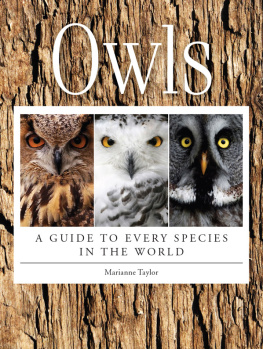

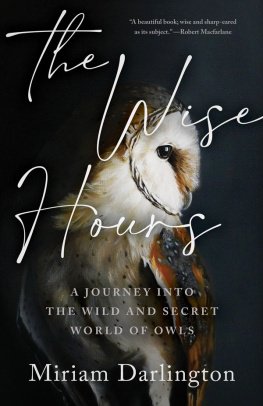

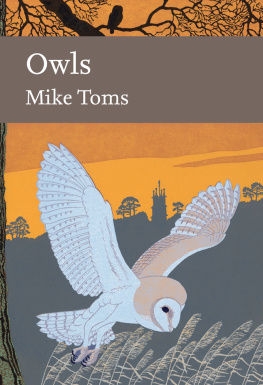

Owls have long held a particular fascination for people. Its hard to think of any living things that are as familiar and yet as mysterious. When we look into their forward-facing eyes we see, or think we see, intense and humanlike expressionsfrom profound thoughtfulness to comical astonishment. No wonder we see more representations of owls than any other birds in our day-to-day lives, as charming characters on-screen and in books, and as decorations for our houses and yards.

However, the way most owls live their lives means that it is a truly rare experience to encounter one in the wild. The archetypal owl is nocturnal, and an inhabitant of dense woodland, hidden in time and space. When it hunts, it flies on cushioned, soundless wings, giving nothing away, and bringing sudden, violent death to its oblivious prey. Its cryptic plumage renders it invisible by day, blending into its background of forest colors and patterns. Only its mournful, far-carrying calls in the dead of night reveal it is there at all.

Over the millennia, a rich fund of owl-related myth, legend, and lore has been passed down the generations. Rigorous scientific study of the birds has gained momentum in the last couple of decades, and in many cases the truth about owls and their lives has proved no less astonishing than the old stories. However, of the worlds 220 or so owl species, many are still virtually unknown and have only ever been glimpsed by a lucky handful of people, much less properly observed and studied. With the destruction of wild habitats proceeding at a frightening pace, learning about how these wonderful and irreplaceable birds live and what resources they need from their habitats is more important now than ever.

Animal evolution can be pictured as a constantly growing, spreading tree. Taxonomy is our attempt to categorize different kinds of twigs and branches, and put names to them all.

Evolution

All birds evolved from a lineage of dinosaurs known as theropods, of which the most familiar example is the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex. Theropods were bipedal dinosaurs, most of them much smaller than the mighty T. rex, and it is now believed that most, if not all, had at least some feathers on their bodies. The earliest feathers were probably small, soft, and simple, supplying a means for the animals to control their body temperature, with larger, color-bearing feathers coming later. Theropods evolved other birdlike traits, including internal air sacs connected to the lungs and to air spaces in the bones and the habit of building nests and incubating their eggs. The best known transitional fossil between theropod dinosaurs and modern birds, the magpie-size Archaeopteryx, shows well-feathered wings that would have permitted flight, and an arrangement of body feathers similar to that of modern birds. It also resembled modern birds in its skull structure, its large brain, and its inner ear anatomy. However, it retained a number of dinosaur features, including a bony tail, a flat instead of keel-shape breast bone, teeth, and claws on its forelimbs.

Archaeopteryx lived about 150 million years ago. Over the next 50100 million years, some theropod descendants lost their teeth and bony tails, and as their bodies grew lighter and their feathers stronger, they became more powerful fliers. Nearly all modern birds (including owls) belong to the most successful of these lineages, the Neoaves, which diversified greatly and made use of many habitats in many different ways. The fossil record indicates that Neoaves directly ancestral to owls were present on the Earth some 57 to 65 million years ago, making the group one of the oldest of all bird lineages.

A great diversity of fossil owls have been discovered and described, some of them assigned to families that are now extinct. Some of these prehistoric owls were different to modern owlsfor example, the extinct family Sophiornithidae were ground birds that chased their prey on foot. Fossil owls belonging to the modern owl families Tytonidae and Strigidae date back at least 20 million years. Initially, Tytonidae was the larger and more diverse group, but Strigidae came to dominate in more recent times.

However, Tytonidae does include some extremely widespread species, so in terms of global coverage, the two families are close to equal. Together, the two owl families diversity and almost global distribution makes for a real evolutionary success story, every bit as impressive as that achieved by the 300 or so species of day-flying birds of prey.

This dinosaur fossil clearly shows full-length flight feathers, as well as reptile traits, such as teeth, claws on the forelimbs, and a bony tail.

Corbis/Xinhua/Xinhua Photo

Him or her?

There is usually little or no difference between males and females in terms of plumage. The most marked exception is the Snowy Owl, in which the females more heavily mottled plumage helps camouflage her on the nest, which may be in an exposed situation. Among diurnal species, such as the Burrowing Owl, males are often paler, because they spend more time outside the nest and become slightly bleached by the sun. As with the diurnal birds of prey, it is usual for female owls to be larger and heavier than males. This may be because the females greater strength is useful for defending the nest against predators and intruders. Meanwhile, the smaller and more agile male spends his time hunting and can keep up a constant supply of small prey for the chicks. Once the chicks are larger, better able to defend themselves, but also much hungrier, the female leaves them and joins the male as food provider.

The order Strigiformes

Owls form the taxonomic order Strigiformes and are not closely related to the other great orders of predatory birds, the Accipitriformes (hawks, eagles, kites, harriers, and buzzards) and the Falconiformes (caracaras and falcons). These are often collectively known as raptors or diurnal birds of prey to distinguish them from the owls. The closest relatives to the owls are probably the nightjars and their allies (order Caprimulgiformes), which share with the owls a nocturnal habit and well-camouflaged plumage but have different body shapes and more aerial habits. The order Strigiformes is subdivided into two familiesTytonidae (the barn owls and bay-owls) and Strigidae (all the rest).

The two owl families break down into a number of groups of closely related species (generasingular genus), and with a little experience, it is usually easy to tell which genus a particular owl probably belongs to, because of a range of traits common to all the members of that genus. However, there are also a number of odd owls out that are the only members of their genus.