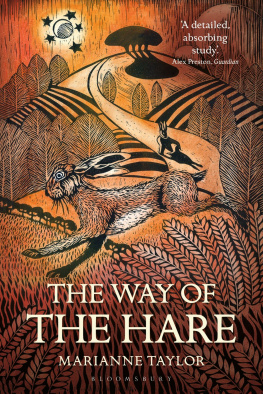

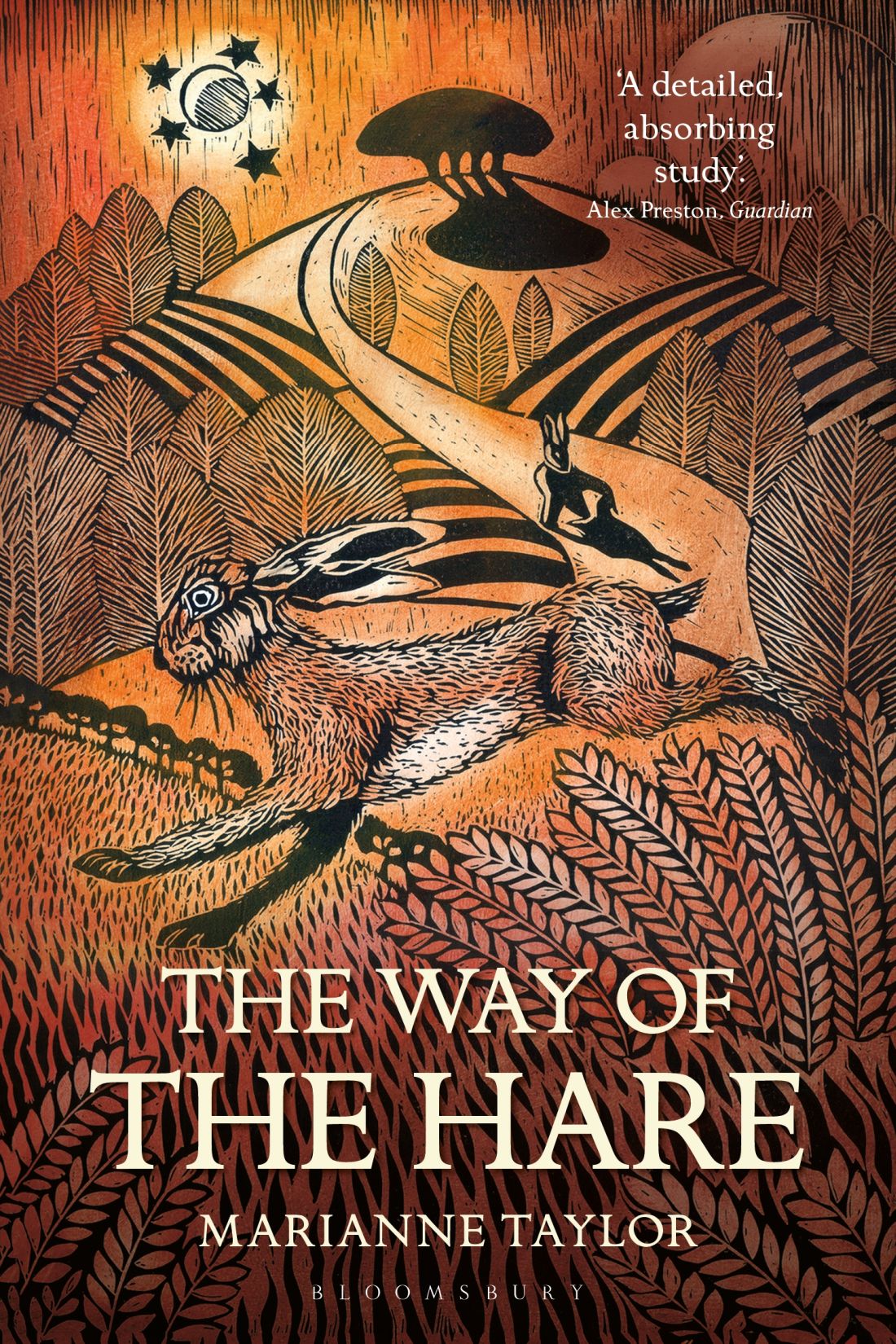

THE WAY OF THE HARE

THE WAY OF THE HARE

Marianne Taylor

Contents

I dont remember the first time I saw a hare. There certainly were hares to see on our family summer holidays in Wiltshire cottages. Theyd appear from nowhere and go racing away through the long meadow grass as we went out on our birdwatching walks. To me they were just big, fast bunnies, nothing terribly exciting, not compared with the birds that were my obsession. And because they were there and gone in a heartbeat, there was no chance to see that there was anything more to them.

I do, though, remember the first time that I looked at one, properly. I was at Rye Harbour Nature Reserve in East Sussex. Id have been 17 or 18. My boyfriend, Joe, had grudgingly agreed to come birdwatching with me. We sat in the hide, overlooking a shallow lagoon teeming with screaming, flapping, frenetic avian life. There were redshanks and Sandwich terns and teals and wagtails, and Joe made polite noises, but I could tell he wasnt exactly gripped. Then I noticed a brown hare making its way along a sparsely vegetated shingle bank. I wasnt particularly surprised by this Id seen hares here before. But I pointed it out to Joe, and he showed proper fascination for the first time. His interest sparked mine. I looked at the hare.

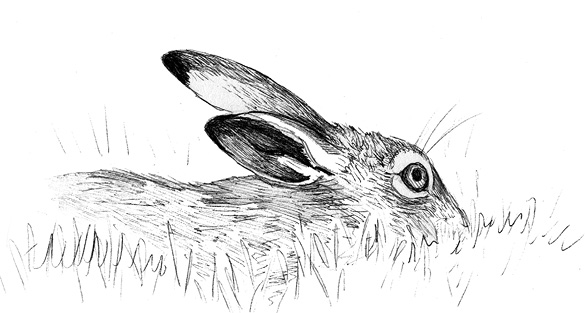

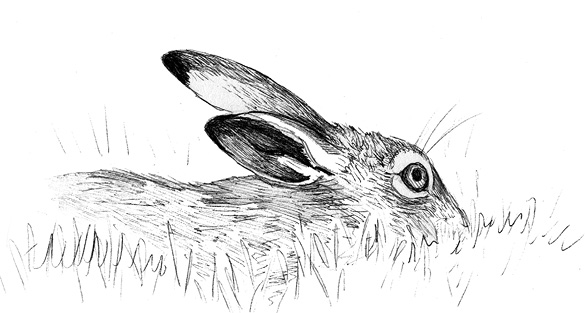

It was a way off, and shimmered in the heat haze that silvered its rough-looking tawny coat. Bony joints and long, lean muscles shifted under its fur. It moved in a curious slow, exaggeratedly awkward way on its precipitous supermodel legs, a sort of half-hop half-shamble of tightly contained power, nothing like the comfortable round-rumped lolloping of a rabbit. Its ears were lovely and ridiculous, tall, broad radar dishes, nothing like a rabbits. Its head was shaped like a toy bus, and its high-set staring eye, even over that distance, was wide and pale and looked utterly haunted, on the edge of reason. Not even slightly like a rabbits. It had the look and wary demeanour of some delicate, leggy, hoofed animal on the brink of bolting, a deer or antelope or even a racehorse, wrapped up in a slightly twisted minds caricature of a rabbit. It didnt bolt though because it didnt know it was being watched. It found some plant that it liked the look of and plucked it from the ground. It ate sitting upright, the greenery moving from side to side in its mouth and slowly disappearing as it chewed. Its wild eyes stared and stared. How had I ever dismissed this beautiful, strange thing as an oversized rabbit?

It was another year or so later that I saw my first mountain hares. I studied at Sheffield University, on the edge of the Peak District. I spent as much time as I could exploring the hills, checking out the fast-flowing rivers with their dippers and grey wagtails, the oak woods full of pied flycatchers, the stone-walled little meadows on the gentle slopes and the achingly pretty villages tucked betweem them. Once in a while my birding friends and I would drive out into the bleak Dark Peak of the north-west, looking for red grouse and golden plover, and the other hardy birds that live on the highest tops. One winter day, we were driving home at dusk along some tiny single-track road over endless black, snow-patched heather moorland, and suddenly there was a little party of white ghost hares loping away from the roadside ahead of us. We stopped the car and watched them go. They were not running full-tilt, barely more than ambling, but were lost to our gaze within moments, swallowed up by the foreboding black hugeness of the moor. The landscape for as far as we could see seemed so bleak featureless, utterly exposed. And freezing. I knew the hares didnt burrow, so all they had for shelter were rocks and heather clumps. And yet this was the most southerly outpost of mountain hares in Britain.

Seeing hares by mistake, while out looking for something else, seemed easy enough. But when I started to work on this book and began to set out into various wild places with the intention of seeing hares, I found that luck was not on my side. Take a certain hot sunny day a couple of Augusts ago, which saw me standing on a footpath alongside a big field, my binoculars pressed to my sweaty brow, scanning back and forth, near to far. The field stretched away into the distance. It was the same field that Id seen in photos, with a dozen or more brown hares drag racing across it, but today, under that too-intense sun, there were none. I plodded on. A few lapwings yodelled overhead, and gatekeeper butterflies danced along the boundary hedge. High overhead, two newly fledged red kites wheeled and squealed and tumbled, thrusting talons at each other. The dispute was over the scrap of prey one of them had, the severed and stripped-bare leg of a tiny bird. I was amazed how much energy they were investing in it when I was finding my slow walk quite hard-going in the throbbing heat. There was certainly plenty to see at the beautiful RSPB reserve of Otmoor, just not the one thing that Id particularly hoped to see not today. I stopped to scan the field again and it remained hare-less, and it was obvious now that it would stay that way for hours. Over the last few years, Ive learned quite a lot about how to not find hares. Of course, every failure just made the addiction worse, and bolstered my determination to find them. Hares are tricksters, and humans never learn.

Most days, sad to say, looking for hares isnt an option because Im not in hare country. On many days, I dont even make it out of town. That doesnt mean wildlife-watching is off the table though when youre hooked, youre hooked, and theres something to see almost everywhere. St Jamess Park in London, for example, is a lovely place in which to stroll and admire ducks, geese and even pelicans. But it isnt the place to see hares, or even rabbits, at least not living and breathing ones. However, there are fabulous numbers of hares to see at the Society of Wildlife Artists annual exhibitions, at the Mall Galleries opposite the park. I have been to these exhibitions most years since about 2004 and admired the image of the hare painted, drawn, etched, printed, carved and sculpted a cornucopia of interpretations. Hares have been prominent in many other exhibitions of wildlife and nature art that Ive viewed hares in every medium and every mood.

Harriet Mead sculpts animals from random scrap metal she fashions her hard-running hares from shovel heads and other old garden tools, horseshoes and toothed gear wheels, all reddened with rust and spliced together in airy yet robust structures. Max Anguss Alexander and Racing Hares is a beautiful linocut of four hares in racehorse mode, crossing the neat bands of a ploughed field. Another linocut, by Andrew Haslen, is Hare and Rook , a rufty-tufty hare resting in a sparse crop field, its coat rendered in white, gold and frosty blue, fixing a passing neon-blue rook with its worried, unblinking stare. Nick Mackmans hare sculptures are bronze, weighty and lustrous, sitting upright and examining the world with the expressive puzzled gaze of the real thing. David Bennetts sketch March Hares captures a string of chasing hares in deft loose daubs of oil paint. The animals are vividly alive, dashing over a rain-freshened green meadow beneath a wild, stormy sky.