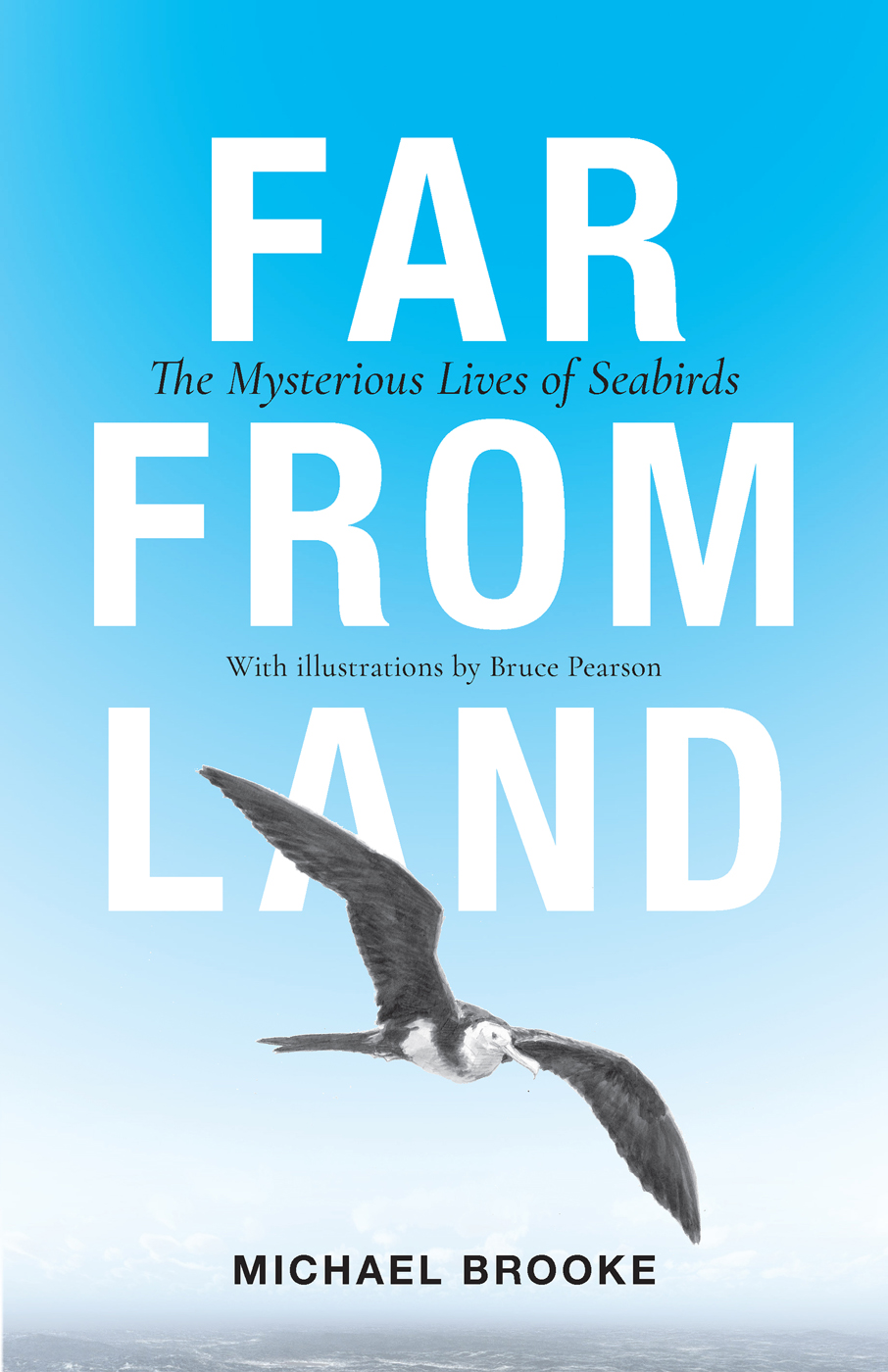

FAR FROM LAND

FAR FROM LAND

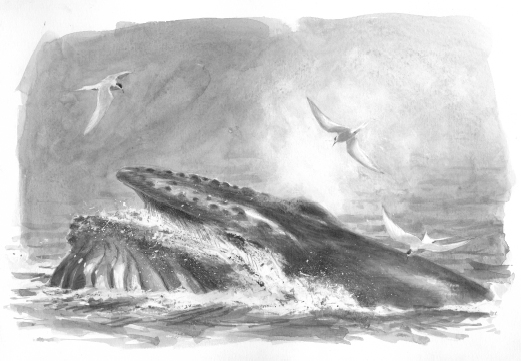

The Mysterious Lives of Seabirds

MICHAEL BROOKE

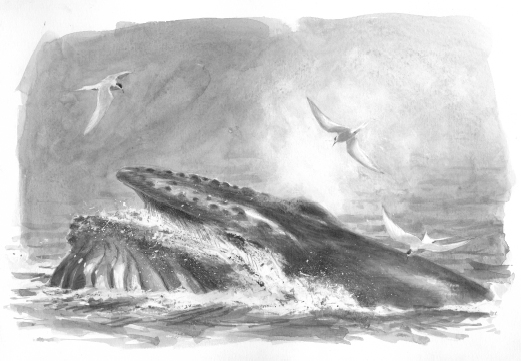

With illustrations by Bruce Pearson

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration by Bruce Pearson

The Arctic Terns Prayer by Mary Anne Clark quoted with the

authors permission, and previously published by the Poetry Society

and as a Challenge winner by Cape Farewell.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17418-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017958318

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Cormorant Garamond and

Helvetica Neue LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Dedicated to any and everyone who loves the sea

CONTENTS

A PERSONAL PRELUDE

It is a happy fact that people following many different callings will aver that they have the best job in the world. A high-altitude mountaineer surely realises how intensely precious is life, his life which hangs by a centimetre thickness of rope as the sun rises over eastern peaks. An art historian can visit the National Galleries in London or Washington and thrill equally at how the fierce, even angry daubing of bright paint yields a Van Gogh masterpiece. But let me throw into the debate another, perhaps unexpected occupation, the seabird biologist. What could be more exciting than visiting stupendously dramatic far-flung islands, encountering exquisite creatures, and trying to answer questions about their daily lives.

In brief support of my case, I proffer some personal highlights from the past 40 years. Friends and colleagues in the same trade could easily offer matching stories, occasionally blemished by tragedy stemming from the ever-present menaces of immense cliffs and unforgiving waters.

My first serious encounter with the milling throngs of a seabird colony occurred in that interval between school and university. For six weeks I served as seabird assistant on Fair Isle in the far north of the United Kingdom. There were birds to be ringed. First catch your bird. As we entered a stinking cave at the base of Fair Isles immense cliffs, a European Shag left its nest in the inner darkness and flew towards daylight. When it passed my companion, he extended a strong arm and caught the Shag by its long extended neck. History does not record whether captor or captive were the more surprised. But the Shag was none the worse for its irregular interception, and I was hooked.

A few years later an undergraduate expedition took me to the Shiant Isles in the Minch, the channel between the Inner and Outer Hebrides. So rich are these seas that catching Pollack for supper is a quicker endeavour than visiting the fishmonger at home to buy less-fresh Pollack fillets. Owned privately by a family who generously see themselves as custodians of the islands and place few restrictions on access, the Isles offer a world class spectacle. Razorbills and Common Guillemots galore nest amid tumbled basalt boulders the size of a decent room. Atlantic Puffins circle like swarming bees above the boulders, sometimes clockwise, sometimes anticlockwise. There I learnt the truth about puffins. They may draw tourists by their clownish appearance and ability to grasp tens of sand eels in a single beakful. But they are horrible to handle. The beak is strong and sharp, as are the claws. It is all but impossible to hold them in a way that leaves ones hand safe from biting beak or scratching claws.

Having censussed the puffins of the Shiants, probably Britains second largest colony, and completed a doctoral thesis on the biology of another burrow-nesting seabird, the Manx Shearwater, I was offered the opportunity to go south. Who could resist six months on Marion Island in the Southern Ocean? On rainy days, a huddle of chocolate-coloured King Penguin chicks looked as unreservedly miserable as a Highland bull presenting its rear to the driving squalls of a Scottish winter. When the showers had passed, shafts of sun slanted onto a gathering of tens of thousands of noisy adult penguins, picking out their black faces, orange ear patches and saffron-yellow upper chests. How I enjoyed the miraculous merging of strident cacophony and vivid colours against snowy peaks.

A few years later I scaled up 1,000 metres to reach the fern forest topping Isla Alejandro Selkirk in the Juan Fernndez archipelago west of Chile. My mission: to census the Juan Fernndez Petrels, whose entire world population, nourished by flying fish and squid, nests on this one island. For the better part of two weeks I clambered among the 4-metre ferns, counting burrows by day. By night I thrilled as a million pairs, give or take, visited the colony and, flying boldly into the swirling mists, crashed through the fern canopy to land near their burrows. It was towards the end of their laying period and some birds had failed to lay in burrows, as per natures blueprint. Instead, caught short, they laid on the ground. The egg was doomed and so I gathered enough eggs to thrive on a daily omelette, cooked on a small smoky fire just outside the tent. But the ground under the ferns was peaty, and eventually started to smoulder. If my activities set the colony alight, that would be catastrophic. Nearby, water was scarce. The only solution was to stand up

Ten years later I headed south again out of Cape Town towards the Norwegian sector of Antarctica. After navigating the big grey seas of the Southern Ocean, the Norwegian research vessel, R/V Polar Queen, thumped through the Antarctic pack ice for several days. I never quite became accustomed to the clattering noise of ice sliding past the vessels hull so it was with relief that we reached the permanent ice and could go no further. There we boarded a helicopter and flew inland for 50 minutes over white nothing. Abruptly, stony snowless mountains reared out of the ice. We landed on the margins of the worlds largest known colony of Antarctic Petrels, 200,000 pairs apparently happy to nest on the snow-free slopes, albeit at least an hours flying from the sea. Did this distant site protect the birds from the rapacious predatory South Polar Skuas? To answer that question was the objective of our study.

These are some highlights from a lifetime as a seabird biologist. My work has mostly entailed studying the birds ashore, and remaining frustratingly ignorant of the birds activities at sea. Only over the last 20 or so years have modern electronic devices begun to reveal the details of those activities. The revelations are astounding. They have enhanced the wonder of seabirds. This book aims to share that wonder. It feels as if seabird enthusiasts have suddenly found the long-sought key to the door that allows an escape from dark ignorance to a new vista of wondrous knowledge.

FAR FROM LAND

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to the Worlds Seabirds

Past Knowledge and New Revelations

I remember, at a recent international conference, a seasoned researcher receiving a medal celebrating her distinguished career in seabird research. Her cheeks had the sheen of a farmers, well-polished and apple-red from exposure to the Scottish wind. She recounted how she had sat atop the islet of Ailsa Craig during her earlier doctoral studies and wondered where the gannets, nesting on that granite lump in the Firth of Clyde, went when they flew beyond the horizon. She had no idea, and nor then did anyone else.

Next page