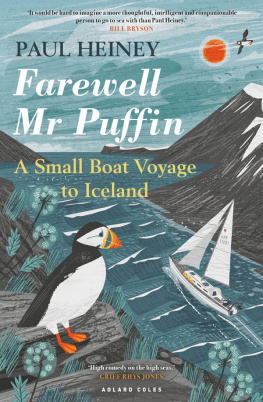

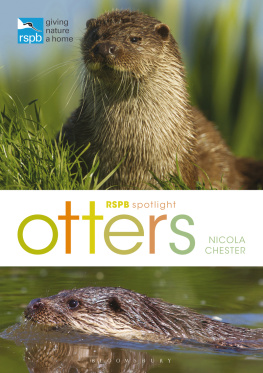

With its unique rainbow beak, the Puffin is unmistakable in the seabird clan.

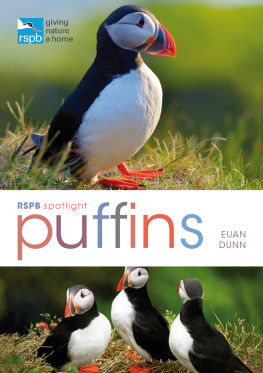

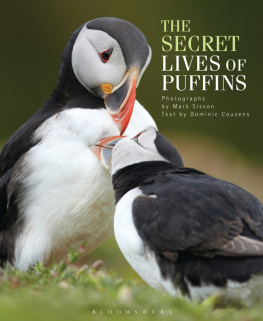

If you ask someone to name any British seabird, or indeed any British bird at all, the chances are that Puffin will be among the first names to spring to their lips. The Puffin is one of our best-loved and best-known birds, amounting almost to a national treasure. It adorns childrens story books, has graced postage stamps and is the photogenic pin-up bird of magazines so much so that over the years it has featured on the front cover of the RSPBs magazine more often than any other species.

As a family, seabirds in general are a sober-looking bunch, but the Puffin brings a touch of the exotic to our shores. With its garish striped beak, wistful eyes and orange feet, it is the charismatic clown of the seabird world, while its rolling upright gait and dapper dinner-suit plumage invite comparison with penguins and no doubt also with the whimsy in ourselves.

For whatever reason, the Puffin strikes a unique chord with us. It is this empathy that continues to make it by far the biggest star attraction for visitors to seabird islands and reserves around our coasts. So popular and iconic is the Puffin that for many it has become a bellwether for the health of our seas; if Puffins are doing well, perhaps all is well with our coastal waters. On the other hand, if the Puffin is in trouble, our alarm bells cannot help but ring more loudly than if the victim were, say, a gull or a Common Guillemot. In order to gain insight into the state of puffindom and its place in the marine environment, however, we need first to lay bare the daily life of the Puffin and explore how it is adapted to spend most of the year offshore in the storm-tossed ocean and the rest of its existence onshore in the social whirl of a colony.

There is something in the Puffins look that chimes with ourselves.

The Puffins cousins

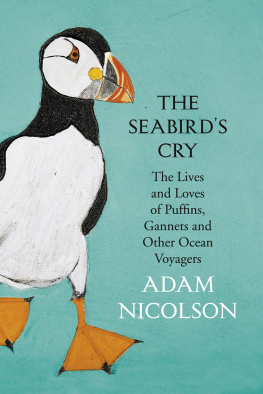

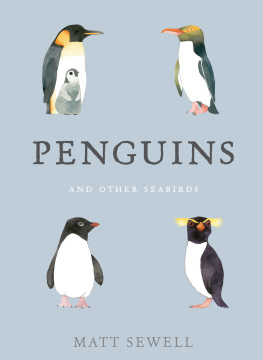

Puffins belong to the family of 22 species of seabird known as auks, a group of compact, pigeon-sized birds thriving on a diet of small fish and crustaceans, which are chased underwater and caught by the birds. Though they undertake extensive seasonal migrations, Puffins and indeed all their fellow auks are confined to the northern hemisphere, where they fill the same niche in the marine environment as penguins do in the southern hemisphere.

Global distribution apart, penguins differ from Puffins and other auks in one other key respect they are all flightless, whereas all auks can fly. The only exception to this is the Great Auk, which paid the ultimate price for its flightlessness by making itself an easy target for man. The magnificent Great Auk was hunted to extinction in the 19th century, the last known British individual having been killed on the remote island of St Kilda in 1840. Four years later the last two known survivors of the species met the same fate on Iceland.

There are four species of puffins, three of which live in the North Pacific. The species that is found in the UK and continental Europe, and the smallest of the four, is confined to a broad swathe of ocean straddling the North Atlantic from New England (USA) in the west to Novaya Zemlya (Russia) in the east, numbering in total an estimated 20 million individuals. To distinguish it from its Pacific relatives, our Puffin is formally known as the Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica), but for simplicity in this book we mostly just call it the Puffin.

Our Puffin is formally known as the Atlantic Puffin.

Pacific Puffins

The Horned Puffin.

The Tufted Puffin.

The Rhinoceros Auklet.

The names of the three Pacific puffin species all reflect their dramatic facial decoration in the breeding season. The Horned Puffin (Fratercula corniculata) most closely resembles our Atlantic Puffin, but it has a largely yellow bill and a small fleshy horn projecting above each of its eyes. The Tufted Puffin (Fratercula cirrhata) is the largest of the four, with a massive orange bill, long, straw-coloured plumes sweeping back from its crown and a blackish body. Lastly, and least Puffin-like of all, the Rhinoceros Auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata) is so-called due to the pale, horn-like knob sticking up from the base of its upper bill, but this puffin lacks the spade-like conical bill of the other three species and also has much drabber, sooty-brown plumage.

A rare vagrant

The Pacific trio of puffins wander widely within their own oceans but, as far as the records show, not beyond them. So the sighting of a Tufted Puffin (Fratercula cirrhata) the first ever record for Britain on the north Kent coast in September 2009 was a jaw-dropping moment for the few birdwatchers who had the great good fortune to spot and photograph it. Perhaps the bird was swept across the Atlantic by a gale. Alternatively, climate change may have played a role in its initial escape from the Pacific to the Atlantic, given that melting ice in the Arctic is increasingly opening up a sea corridor north of Canada where previously there was an impenetrable frozen barrier to the free passage of seabirds.

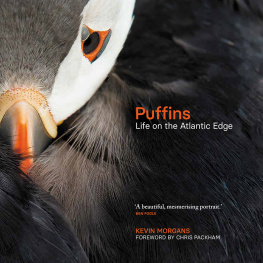

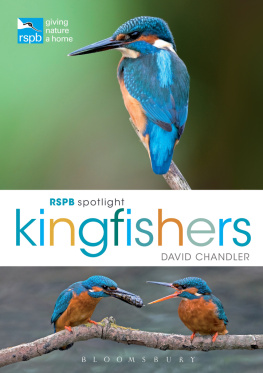

The gaudy sea parrot

Like its Pacific relatives, in adulthood our Puffin possesses remarkable facial adornments in summer. The centrepiece is a conical beak of brick-red, blue and cream, much deeper than it is wide, and featuring curved, vertical grooves (see chapter ), an effect that earned the bird its ancient name of sea parrot. On either corner of the base of the beak nestles a fleshy saffron-yellow rosette, its wrinkling making it look a bit like a walnut kernel. Each dark eye is encircled by a crimson ring, above and below which are small, bluish plates, the triangular upper one lending the Puffin a look that hovers between wistful and a quizzical who me? The visual impact of all these decorative effects is concentrated by a backdrop of greyish-white cheeks.

The base of the beak is flanked on either side by a distinctive fleshy rosette.

The Puffins gaudy clowns mask is worn only during the breeding season.

In addition to the show of colour on the head, the legs and feet are an equally eye-catching orange. All this colour intensity is heightened by the monochrome plumage covering the rest of the adult Puffins body, a dazzling white breast contrasting with black upperwings, back and tail. The black sweeps up over the crown of the head to the base of the beak like a hood. It is this friars cowl feature that gave rise to the Puffins scientific name, Fratercula arctica, meaning little brother of the Arctic. The Puffins portly, barrel-chested outline only serves to reinforce this friar-like impression.