Acknowledgements

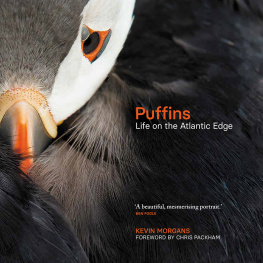

Mark Sisson Although wildlife photography as a profession is by its very nature often a solitary business, there are several people and organisations I need to thank for their help in making the portfolio of images in this book a reality.

The first of these is my wife Caroline who, along with the rest of my family, puts up with my long absences in the pursuit of my work and supports me in the process. Thanks to all who have joined me on a number of the trips involved, specifically fellow photographers Danny Green and Paul Hobson who have also provided advice and inspiration at the times when it was needed, and Kevin Treadwell who has helped me out when additional photographic kit became a necessity beyond my budgets! Also all involved with the management of Skomer Island and Fair Isle Bird Observatory where over a number of years I have stayed and spent many days and weeks with your puffin colonies. Finally to those who manage the conservation at the many other colonies in the UK, Iceland, Ireland and Norway where I have done the same: without your work the many pressures on puffins would have a greater toll.

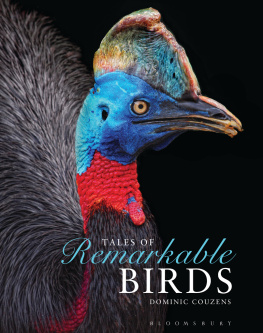

Dominic Couzens I thank my wife Carolyn and children Emmie and Sam for keeping me sane while earning a living as a writer. Thanks to Lisa Thomas for believing in this project, and to Mark Sisson for re-establishing a friendship that began at school.

THE PUFFIN

The Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica) is a small seabird with an outsize, brightly coloured bill and orange legs. It belongs to a family known as the Auks (Alcidae), along with 20 or more other species, of which five others, the Guillemot (Uria aalge), Razorbill (Alca torda), Black Guillemot (Cepphus grylle), Little Auk (Alle alle) and Brnnichs Guillemot (Uria lomvia) also breed in Europe, often in the same locations as puffins. Its world breeding range encompasses the North Atlantic coasts of Europe and North America, hence the name. There are two other species of puffin, the Horned Puffin (Fratercula corniculata) and the Tufted Puffin Fratercula cirrhata), both of which occur on the Pacific coast of North America and Asia. They are not covered in this book.

For a seabird, the Atlantic Puffin is diminutive. It stands just 1820cm tall (78in), which is about as tall as a paperback novel, and it is 2629cm (1011.5in) long from the tip of its bill to the end of its short, pointed tail. By comparison, a guillemot is 46cm (18in) long and a herring gull up to 60cm (24in) long. The puffin weighs between 350 and 600g, while the herring gull weighs up to 1500g. Seeing these figures it is easily understandable how puffins can be bullied by herring gulls and other birds.

In terms of colour and pattern, almost everybody knows what a puffin looks like. If you stop to think about it, this fact is quite surprising, because not many people have ever actually seen a puffin in the flesh. It lives during the summer in remote places that are often hard to get to, and in the winter it disappears out to sea. So it isnt as though the puffin is a well-known, back garden kind of familiar neighbour. The truth is that most of us only know it second hand. But the puffin has such a singularly unusual shape and colour that it captures the imagination.

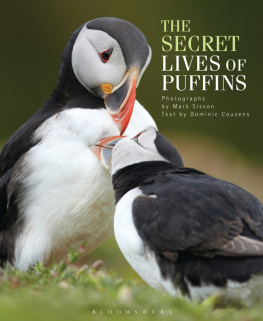

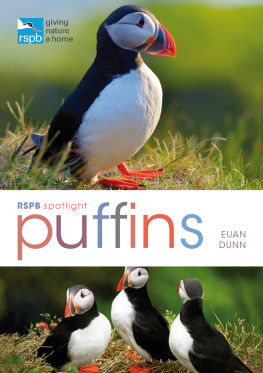

Portrait of a puffin in breeding plumage. In common with many seabirds it is black above and white below, with the only colour on the legs and head.

The puffin is a portly but upright bird, with a plump body, very large, rounded head and extremely short, bluntly pointed tail. The legs are quite long, so that puffins can walk and run quite well on land; their relatives the guillemot and razorbill have short legs and can only waddle at best. The tarsus (main leg bone) of the puffin is thick and rounded, while the feet have three well clawed toes joined by webs. At first sight, the most obvious feature is the remarkable bill, which is triangular in shape and, in the breeding season, spans the height of the head from crown to chin. Although large, the bill is laterally compressed, so that it looks narrow when the bird is face on. The bill is also highly coloured and unmistakable, and often described as parrot-like: the outer part is deep orange and the inner half dark bluish-grey, and there is a yellow chevron-shaped line dividing the two parts. There is also a yellowish fleshy plate dividing the upper mandible from the forehead and a bright, wrinkled yellow rosette of bare skin at the base of the mouth. Depending on the age of the bird (see below), there are a number of yellowish grooves on the outer part of the bill.

As far as plumage is concerned, the puffin is boldly black above and brilliant white below. The black extends from the forehead over the crown, and covers the back, the whole of the wings and the tail. There is also a black band across the chest. In late summer the black feathers wear a bit and may look browner. Below the chest the underparts are entirely clean white apart from a dusky patch on the flanks, and the underwings are dusky grey, a good distinction from razorbills and guillemots, which have glinting white under the wing. The face is greyish white, darkest on the throat. There are no plumage differences between male and female puffins, but the male is consistently slightly bigger and heavier than the female, although this distinction is not visible in the field.

As you might expect, the puffin has a broad gape. This gives it a good reach when catching fish in its jaws underwater.

The tongue is relatively large, and orange in keeping with rest of the gape. The tongue helps to keep the fish secure when the puffin is carrying them back to the burrow. For this purpose it is fitted with small, backward-projecting spikes.

The neck ring of this individual is narrower than that of the bird above, and there is a wavy lobe of black on the side of the breast.

The face isnt quite white, but actually a light ash-grey, and the precise shape of the face pattern varies quite a bit between individuals. In this bird, the grey comes to a neat point towards the back of the head.

This book, by the way, only showcases puffins in their breeding plumage, as described above. However, in winter puffins undergo some changes. The most obvious difference is that the bill is smaller and doesnt fit so snugly on to the head; indeed it looks a little strange and grotesque, like an outsize nose. It is still colourful, with essentially the same orange and bluish-grey combination, but not quite so bright. The difference in shape is brought about by the loss of horny sheaths on the outer part of the bill. In the spring an adult puffin develops several sheaths and plates on both mandibles, including a rim on the upper mandible and some broad orange plates covering the middle. When not needed in autumn these simply fall off, to grow again next year.

Another major difference from summer to winter is that a puffins face becomes much darker, especially around the eye where it looks charcoal-stained, and the ornaments of spring are lost. The rest of the plumage looks the same as it does in summer.