To my sister, Cathy Hawkes.

Contents

Writing a book can be a solitary and selfish activity, so thanks are owed to Carolyn, my wife, and my children Emmie and Sam, who had to cope at times with an absorbed, distracted husband and father. They did so admirably, with love and grace.

Many thanks to my commissioning editor at Bloomsbury, Lisa Thomas, who got the idea accepted and signed off. Thanks to Anna MacDiarmid and Julie Bailey for taking the project through to its conclusion.

Finally, many thanks to Marianne Taylor for her astute editing and for her delightful line drawings that adorn the chapter headings.

We used to call them adventures. Now that my son is eleven, we call them hikes. Either way, we like to be outdoors, away from people, in the hinterland where wildness and safety dwell together. We were dropped off beside the trunk road that cuts the New Forest in half, and we set off to cross wood and mire, heath and scrub to reach the village of Sway 15km (9.94 miles) to the south. The forest was damp and breezy, quintessentially March, the spring still largely in the mind. There were no brilliant colours yet, only fresh ones. The roadside daffodils in Burley shone but didnt catch fire. Instead, the landscape was full of subtleties: the watery greenish-yellow of hazel catkins, the militarily upright spikes of dogs mercury, the smooth, sunshine-dappled bark of beech green against green, brown against brown. It might seem impossible to overlook a tree that is pink against purple, but alder is that tree, its dense lattices of buds, catkins and bark keeping their colours secret.

Hiking is about curiosity, to find out what lies around the next bend, or at the edge of the wood. It can, of course, be about companionship too, and for us today, father and son, it was two generations and two minds coming upon the same scenes together and reflecting in our different ways. Samuel had not noticed the charcoal-like tips at the end of ash twigs before. On the other hand, I had long forgotten about the attractions of deep mud, something to be ploughed through rather than edged around. For a while, I borrowed his gift of childhood and revelled in the simple joy of getting stuck. Mud and water provide ways to convert a gentle walk into something resembling an adventure.

This being March, I was surprised at one point to see a swallow fluttering determinedly across the side wind, hacking northwards. It was an early arrival, even for the New Forest, in the deep south of England, and the swallow seemed to be struggling in the cold, insect-less air. If swallows could ever regret things, which we are pretty certain that they dont, then this one might have been berating itself about its impetuosity in getting here so soon. Swallows usually fly with effortless abandon, their wings rowing the air currents like expert oarsmen so that, every few moments, they can topple one way or another, zooming up or down, banking, sweeping, playing. Today this swallows light touch was a hindrance. It kept low and its head down.

It was hard not to compare its journey with ours. We were on a leisurely 16-km (10-mile) stroll, for our own pleasure, in each others company, knowing that there was a train to catch at the end to take us back to a warm home. As for the swallow, it had almost certainly flown across the English Channel this morning, closing in on its destination, perhaps now only a day or two away. Its marathon northward journey, at least 12,000 km (7,456 miles) from its beginnings in the Cape region of South Africa, had probably begun in late January. What must it have seen on its travels? Maybe the swallow saw elephants and giraffes, a mass of humanity, the great rainforests of the Congo Basin. Along the way it probably snacked on insects that have not yet been described by science, and perhaps never will be. Its shadow would have passed over trees and clearings never seen by the human eye. We can never know how it registered such things. We cannot say it was interested or excited, and we cannot say if it wasnt, because we dont know how swallows think. We can only guess as to its own level of curiosity, because we cannot measure curiosity in a swallow. We can guess at its motivation, though. The swallow was on a mission, to reach its breeding grounds in good time. It was on its own, unaided, doubtless well ahead of its rivals. Probably that is all that mattered.

The swallows lot seemed stern and burdensome, especially compared to the joy of our benign mission. We could stop any time we were tired, if we wanted to, and there were shops for food well within reach. We didnt have to reach our destination at all; we had only chosen it yesterday. Yet for a swallow, not reaching its goal would be disastrous. If it fell short of last years territory (or its birthplace, if it was migrating for the first time), through tiredness or hunger or even disorientation, it would be starting off the breeding season in a new place, not knowing the ropes and having never met the neighbours. Such things matter for a bird and can make the difference between it reproducing or not. The swallows stakes were as high as ours were minimal.

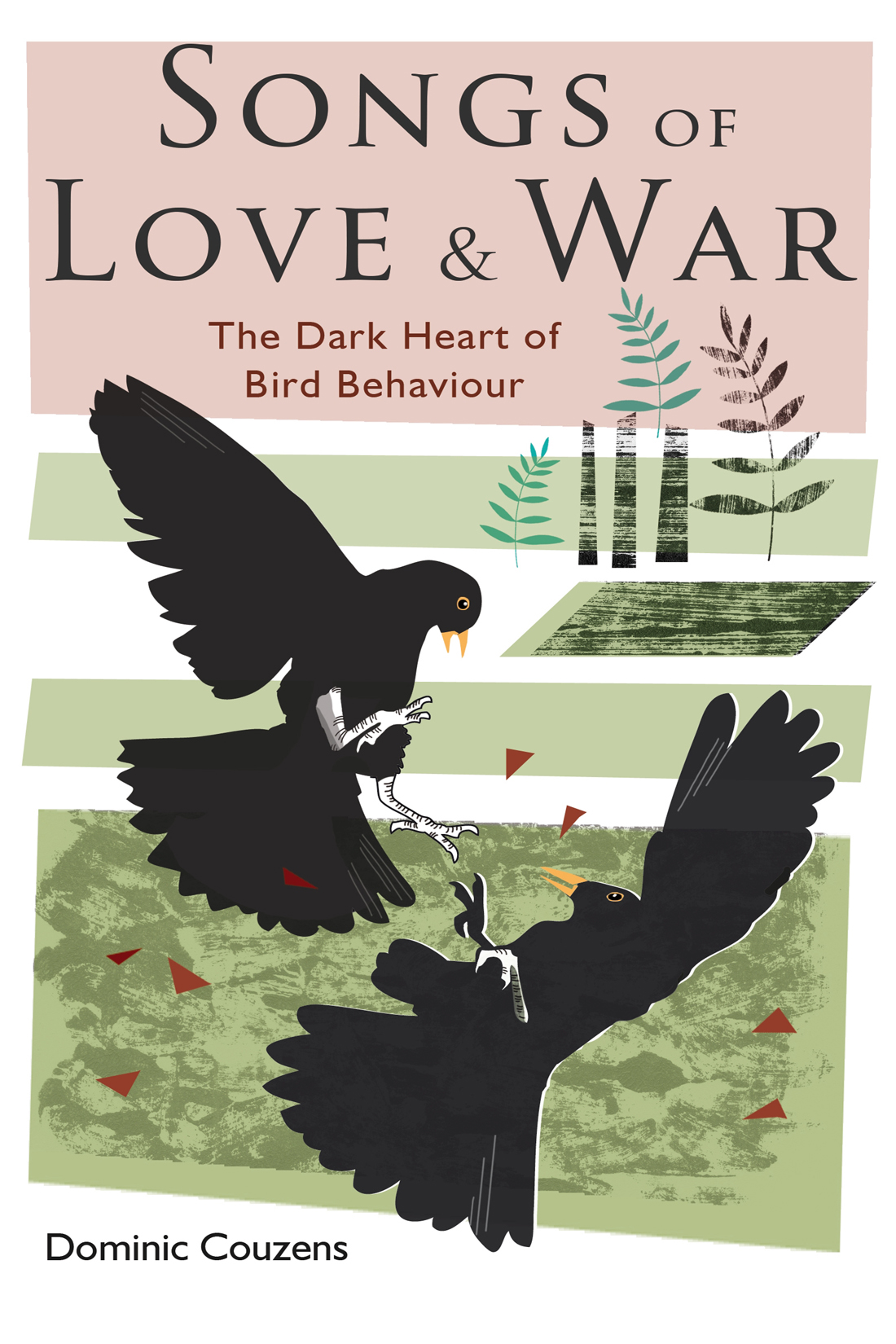

And as we contentedly traipsed through the early spring forest, carefree and curious, I kept being reminded of the burdens and challenges of the birds crossing our path. A pair of crows flapped past, calling to each other. If they hadnt been inky-black and flying with slow, stealthy wing-beats you could have dismissed them as early season lovebirds, cawing with friskiness. And indeed, crows are usually faithful and attentive partners. Yet theirs is an introverted world, where togetherness is a buffer against a hostile neighbourhood. There is mutual aggression from magpies, casual violence, and thats not all. Some of a crows worst enemies are other crows. Settled pairs are often harassed by individuals without a territory, and may even be raided by a flock. Sometimes their eggs and young are destroyed. They must always be on their guard, always ready to defend their territory, primed to fight. They must be watchful and remain healthy. A single bad day might alter the course of their life.

One wonders what goes through crows minds as they follow the course of normal existence on a day like today, a dose of Englishness with blustery air and pretend cold. Do they live on the edge? Do they perceive the constant threat of disaster? Or do they simply react to things? Their lives are shorter and more brutal than ours, but it seems hard to believe that a crow could be riddled with anxiety. It is far easier to imagine that, even when relaxed, they can react with great speed to changing situations.

I said the weather was unremarkable that day, but that didnt mean it was agreeable. As we edged towards Wilverley Inclosure on an old, disused railway line the first drops of rain began to tickle our faces, and we could see drizzle against the conifers on the top of the hill. This was not showy or torrential, just highly professional, moistening rain, lightly spraying the puddles and making the birch buds drip. It didnt stop the birds singing; indeed, the great tits were uttering repeated tee-cher songs with their usual gusto. Great tits provide the most authentic sound of early spring, ringing in the new season in January, just after Christmas, but in the context of that rainy day in March, their cheeriness sounded forced and false, like holidaymakers making loud jokes under grey skies at the seaside.