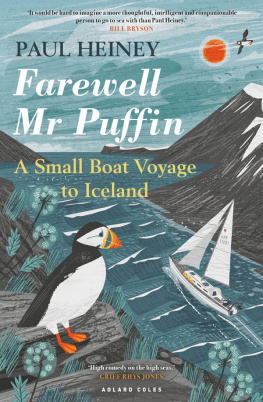

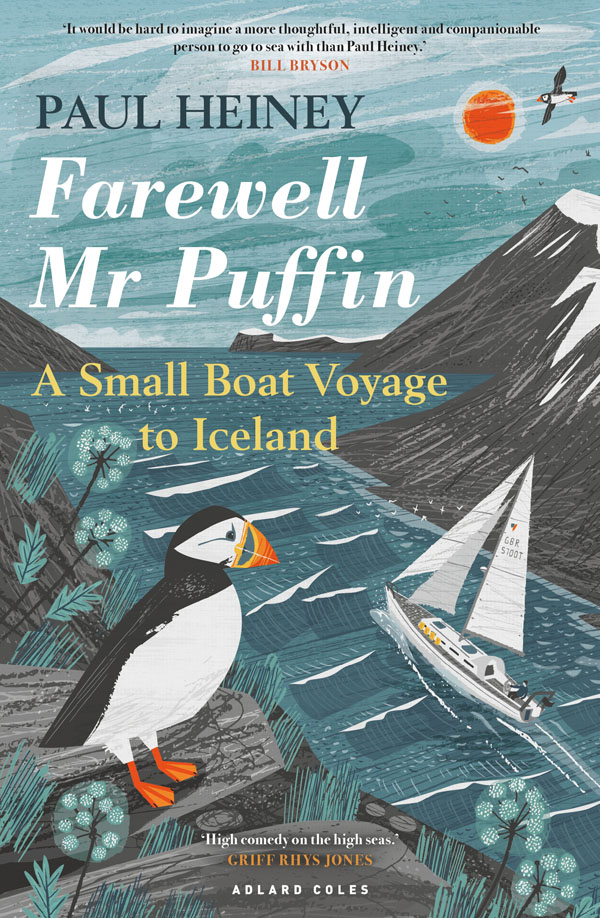

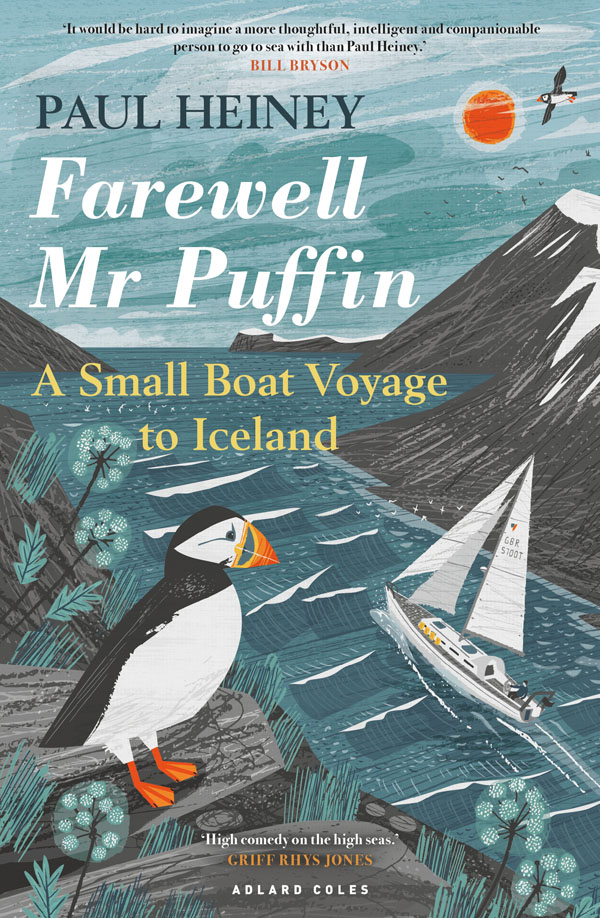

FAREWELL MR PUFFIN

ADLARD COLES

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

BLOOMSBURY, ADLARD COLES and the Adlard Coles logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2021

This electronic edition first published in 2021

Copyright Paul Heiney, 2021

Paul Heiney has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for

ISBN: PB: 978-1-4729-9097-6; EPUB: 978-1-4729-9098-3; EPDF: 978-1-4729-9100-3

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

Contents

The puffin doesnt mind people laughing at him because he knows he is a figure of fun: What bird is always out of breath? A puffin! Ha ha. Life, he thinks, is not for taking too seriously and so he prefers to leave everyone with a smile on their face. He doesnt like fights, or disputes, and this leaves him open to bullying by bigger birds, so he avoids them and wants nothing to do with them. He shuns competition and turns the other multicoloured cheek, thinking to himself, they can fight for supremacy if they wish, but I know my place. It is not cowardice, it is survival.

He is inclined to portliness, which can spoil his upright and long-legged frame, and selfish too at eating time, when he consumes 90 per cent of everything he catches, leaving only the meagre remainder for the folks back in the nest a self-centred creature, perhaps.

He takes few orders from anyone. He is a natural wanderer who will go where the fancy takes him, and that is always towards the sea. This is his real home. He loves cold and chilly waters and the nearer he can get to a snow-bound cliff side the better. Ask him what kind of place he prefers and he will use the word harsh, which is why you will find him if youre lucky, for he is skilled in self-concealment bobbing along on the curling crests of waves as they travel across the dark and bitter deeps of the North Atlantic.

But he knows his Darwinian duty is to breed and for that he must come ashore, which he does with the greatest reluctance. Despite having gone missing for months on end, he will turn up always at the same burrow to be met by the same partner. He is a faithful little thing.

This time ashore is driven by duty and not desire, and when reluctantly approaching land after a spell at sea he is often to be seen attempting to touch down, only to lose his nerve at the sight of so many others. So he takes off again, circles for a time, perhaps several days, then gathers his strength and finally finds the courage to join the throng. He often chooses a day when the visibility is poor so as not to attract attention, unlike most other creatures.

If he has to endure the land, then he makes sure he picks the most remote and spectacular spot that he can. Islands are best because pests and predators cannot bother him there. Cliffs are good, and wild ocean shorelines even better. And there he will sit, making the best of it, but knowing deep down this is not where he really belongs. As if uninspired by his surroundings, he sits idly around most of the day, twiddling his thumbs, unmotivated, and does very little. If he emerges from his burrow he will walk past others with his head down, hoping not to be noticed pretend Im not here.

The land is not his real home and his time ashore is a mere interruption in his maritime life. He likes to feel the salt water swirl around his feet; icy wetness holds no fear for him. All he craves is to live a life unseen and unrecorded. Only at sea can he do that.

***

But thats enough about me. Let us sail north to find the puffins.

I live on the east coast of England, close by a small harbour through which a torrent of a muddy river flows, changing direction with every tide and allowing the landscape to soak up the sea before spitting it out again in disgust. The sea and the land have never been good friends hereabouts always arguing, fighting, the land bravely taking the occasional futile stand against the sea, which, over centuries, has proven to be the infinitely stronger of the two.

To the north is a lighthouse, painted white not only to aid identification, but perhaps to denote the purity of its purpose, which is to give night-time warnings of the many dangers off the shore. At the harbour mouth, red and green lights shine out to guide the very few craft that ever bother to come here. This is where flat, rich farmland gives way to marsh, which in turn becomes sand dunes, then ankle-twisting shingle where it meets the sea. The shore is mean and allows us little golden sand on which dogs can run or in which children can dig.

This is where my voyage started; a journey that was to take me northwards to the colder, lonelier, more exposed climes of the North Atlantic Ocean to places puffins might enjoy.

Boats line both sides of this river at least, as far as the footbridge that connects the village with its nearest town. Most are pleasure craft, but a few inshore fishermen still inhabit this place probably for sentimental reasons, or simply for the chase and the addictive, eternal gamble of catching fish; but there is no living to be made from that game any more. The fishing glory has gone. There is a boatyard that builds and repairs, and here can be grabbed the occasional glimpse of a man working wood to patch a hull, using the same tools and skills of centuries ago. But mostly its plastic boats, like mine, that come here for their annual wash and brush-up.

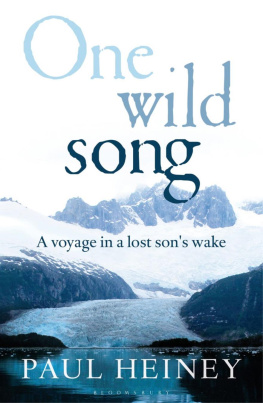

This is where my boat, Wild Song , had spent her winter, undergoing surgery on a scale that, had she been human, might be described as life-changing. Her keel had to be amputated after doubts about its integrity, then replaced carefully so as to leave no visible scar between it and the rest of the boat. Then her heart was taken out the engine removed and a new one transplanted, shiny red as it happens, just like a human organ. But her mast and sails are what really matters, for these were what would drive me along like puffin wings before the breeze. I was well aware that much about her had been fiddled with over the winter during the extensive surgery, leading to uncertainty that she might not work in the ways with which I was familiar. I have probably clocked up nearly 25,000 miles in her and the slightest change in her ways will throw me because there is something about a boat that is more than just a collection of its parts, and by dismantling and putting it back together, like a musical instrument it may be reborn out of tune.

It was mid June, the days warmer and the nights shorter, and they would become shorter still as I sailed north. Ever since the turn of the year, back in the dark days of winter, I had focused on departure day with the enthusiasm of the child wishing for Christmas. At times, the desire to get to sea can be heart-stopping. I had planned and researched, stocked up with food, gathered my nerve, and it was finally time to drop the lines that held us to the shore. Wild Song would soon be underway again. This brave little ship, which had safely transported me far into the South Atlantic Ocean, to Cape Horn indeed, would now give me a taste of what lay at the other end of that great ocean. I have sailed the Atlantic all the way down to its southern fringes, westwards as far as North America, and only the northern wastes of the Atlantic remained undiscovered by me.

Next page