One Wild Song

One Wild Song is a little masterpiece, sometimes thrilling, sometimes, hilarious, sometimes almost unbearably moving A wonderfully told story of the sea, shot through with an authors anguish at the loss of a beloved (and hugely talented) son. I have never read anything like it before and it haunts me still.

J OHN J ULIUS N ORWICH

A terrific adventure into wild and distant waters, and a strong tribute to a sons memory. Paul Heineys story is a new classic of small-boat seafaring and a fine description of the deep south.

S IR R ANULPH F IENNES

A wonderful book, finely considered and beautifully written, that does not spare us the considerable trials of small-boat voyaging, nor the struggle to make sense of the incomprehensible nature of loss. It is an absorbing, moving journey which explores the wonders and frustrations of the sea as powerfully as it explores the mysteries of the human spirit; a journey which ends where all true journeys should end, with a greater measure of peace and understanding.

C LARE F RANCIS

I beg to remind the reader that the work is unavoidably of a rambling and very mixed character; that some parts may be wholly uninteresting to most readers, though, perhaps, not devoid of interest to all; and that its publication arises solely from a sense of duty.

R OBERT F ITZROY, C APTAIN, 1839, INTRODUCING HIS

V OYAGES OF THE A DVENTURE AND B EAGLE

CONTENTS

By the age of twenty-one, my son had sailed aboard a tall ship across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

At the age of twenty-two he wrote a poem which, once heard, can never be forgotten.

At the age of twenty-three he took his own life.

This is what I did next.

LAND SLIPS FROM SIGHT VERY SLOWLY, often more slowly than you would wish. But eventually it goes and in that moment, when the coast finally disappears and you, your little ship and your crew are alone on the sea, lies the torment; for a bit of you wants rid of the sight of land and the real journey to begin, but if you are honest you secretly crave its comforting presence. This is the voyaging paradox and has been for all sailors who take to deep waters. On that fine July afternoon, as the green and secure Cornish landscape dwindled behind me and the blank, grey ocean lay ahead, I was torn over where my true ambition lay: wouldnt life be simpler and safer at home, on land? Yet isnt an ocean voyage the greatest of achievements, if an often dangerous and uncertain business? Which way do you turn your head? Forwards to the unknown or backwards to the safe? The only answer has to be ever forwards, towards the bow. Backward glances are not the ingredients of true adventures.

The start of a new voyage is a time of confused emotions, a tumult of thoughts and feelings every bit as wild as the tumbling of the waves around you. This must be accepted and relished, for if depth of feeling is lacking then there can be no sense of adventure. On the one hand it is also a time of urgency in which you are drawn with all haste to the horizon like a gull to a scrap of fish: you want to be on your way, devouring the journey, making progress, putting miles beneath the keel, getting there. But a little bit of you wishes the land would stay with you, for it spells comfort and refuge while, increasingly, all around you is becoming less certain and you more isolated. On land you can walk with others, at sea you always stand alone.

It doesnt do to look over your shoulder too often, watching for the once distinct outline of land to fade to a blur and then be lost in the haze: this leads to an unnerving feeling that a door has finally closed on the world behind you. This thought will make you swallow hard. Yet once it is admitted, that things have changed and that which was is now gone, and only what lies ahead matters, then you are relieved and rise to the challenge. This transition does not always come easily, but it is at the heart of the satisfaction of voyaging. People talk of voyages of discovery and imagine only of arrivals in new, romantic worlds; but the beginnings and the ends in themselves are the least part of it, for true voyages are an unfolding process of self-discovery and the true drama lies not in the starting or the finishing, but is made along the way.

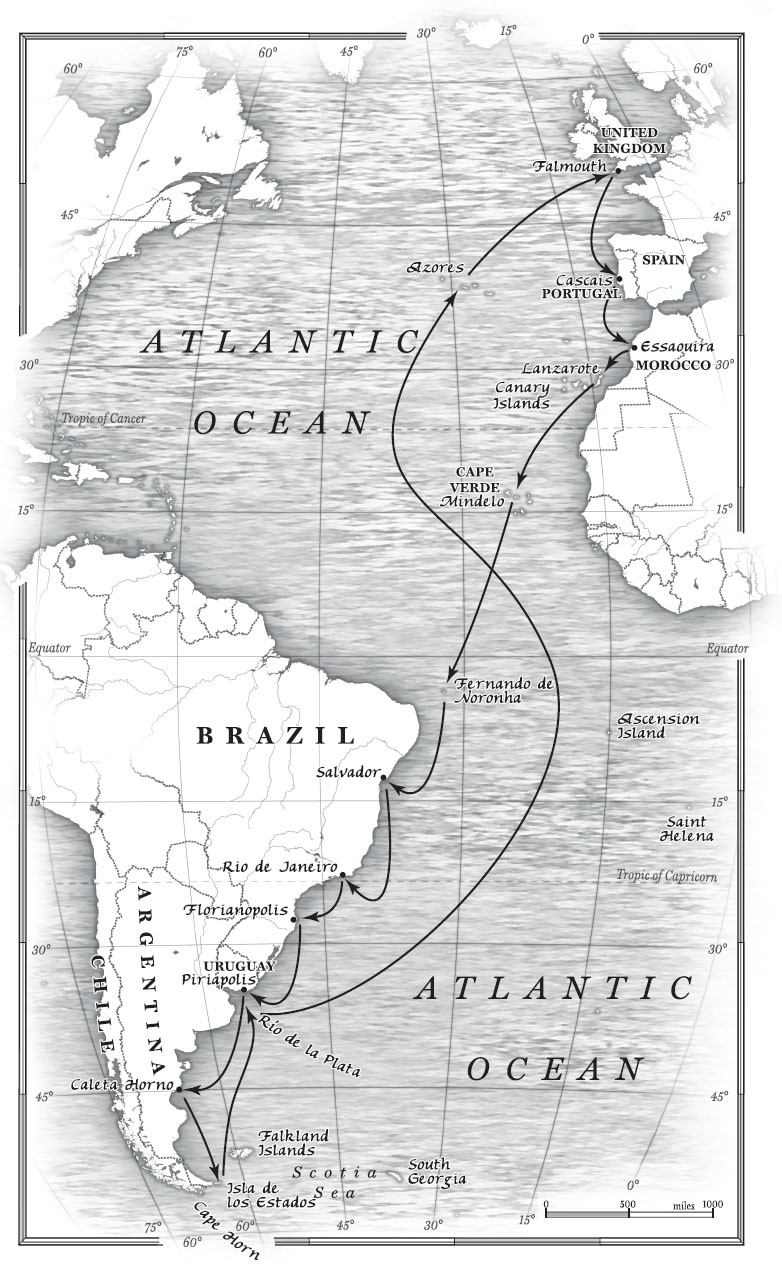

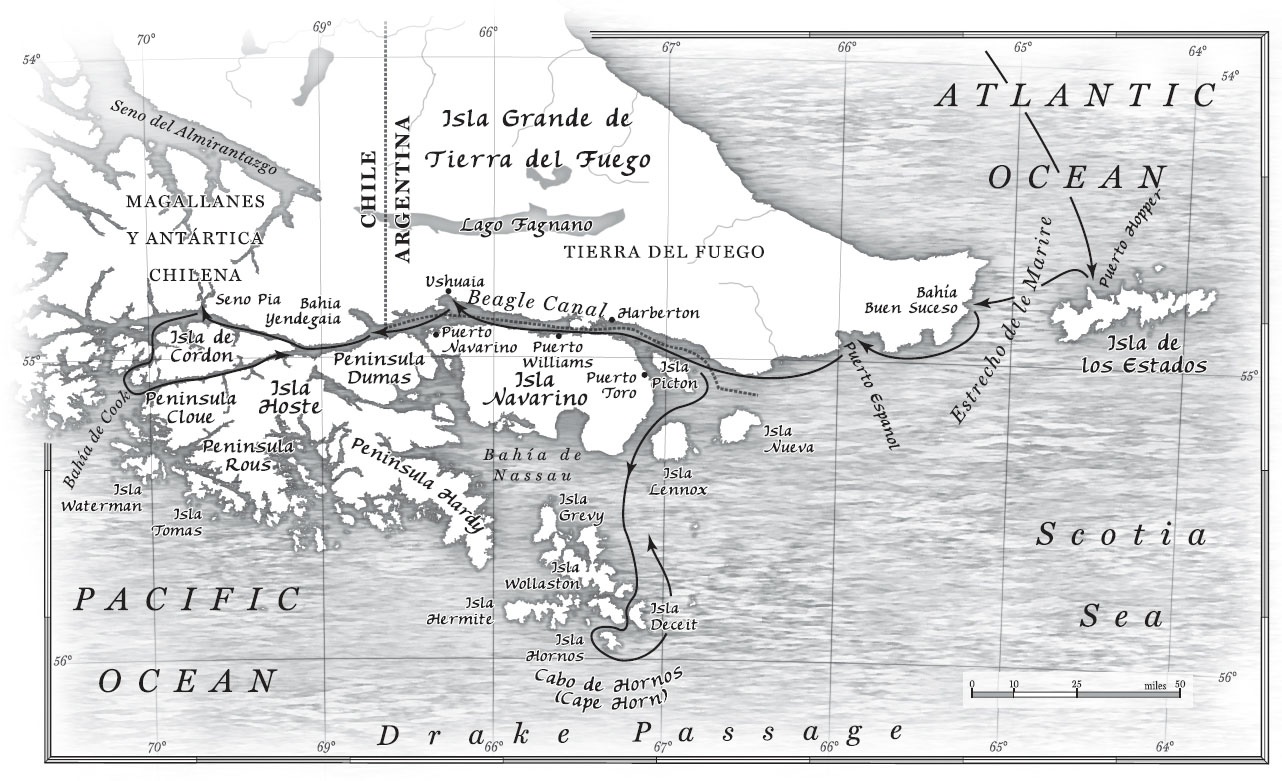

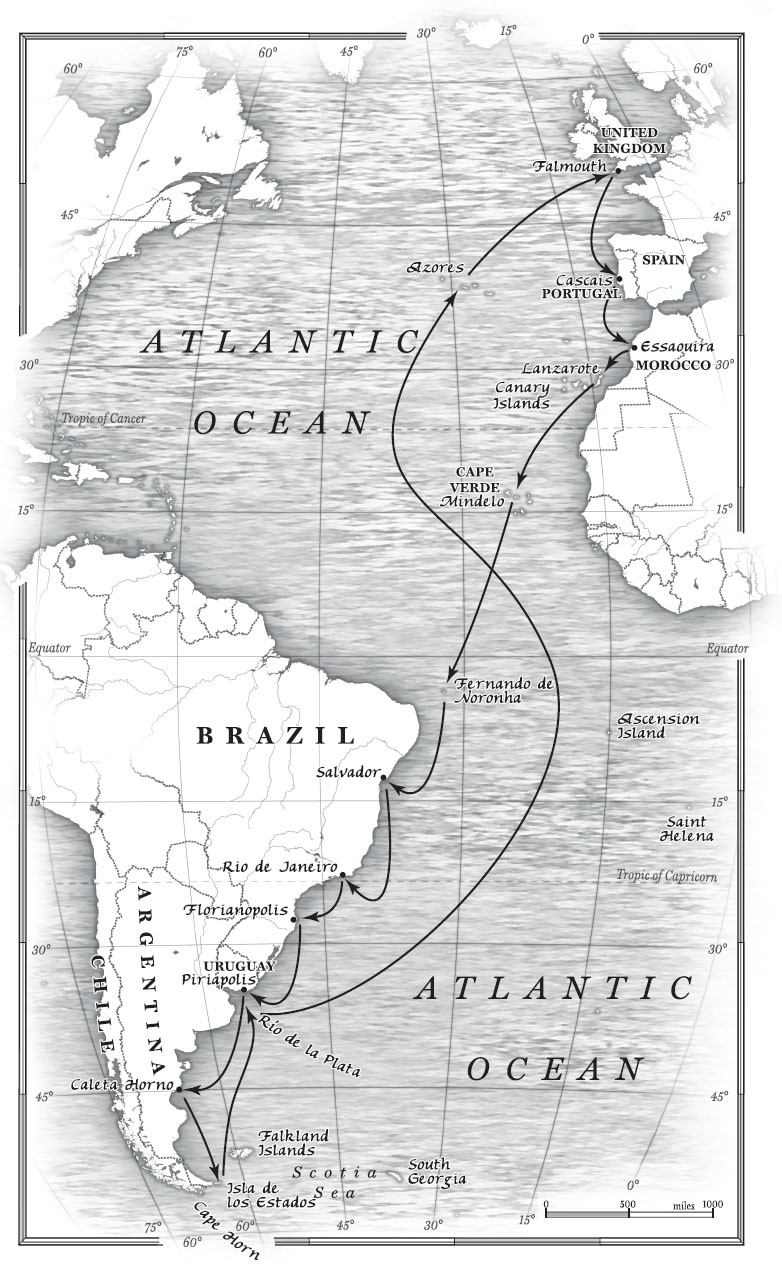

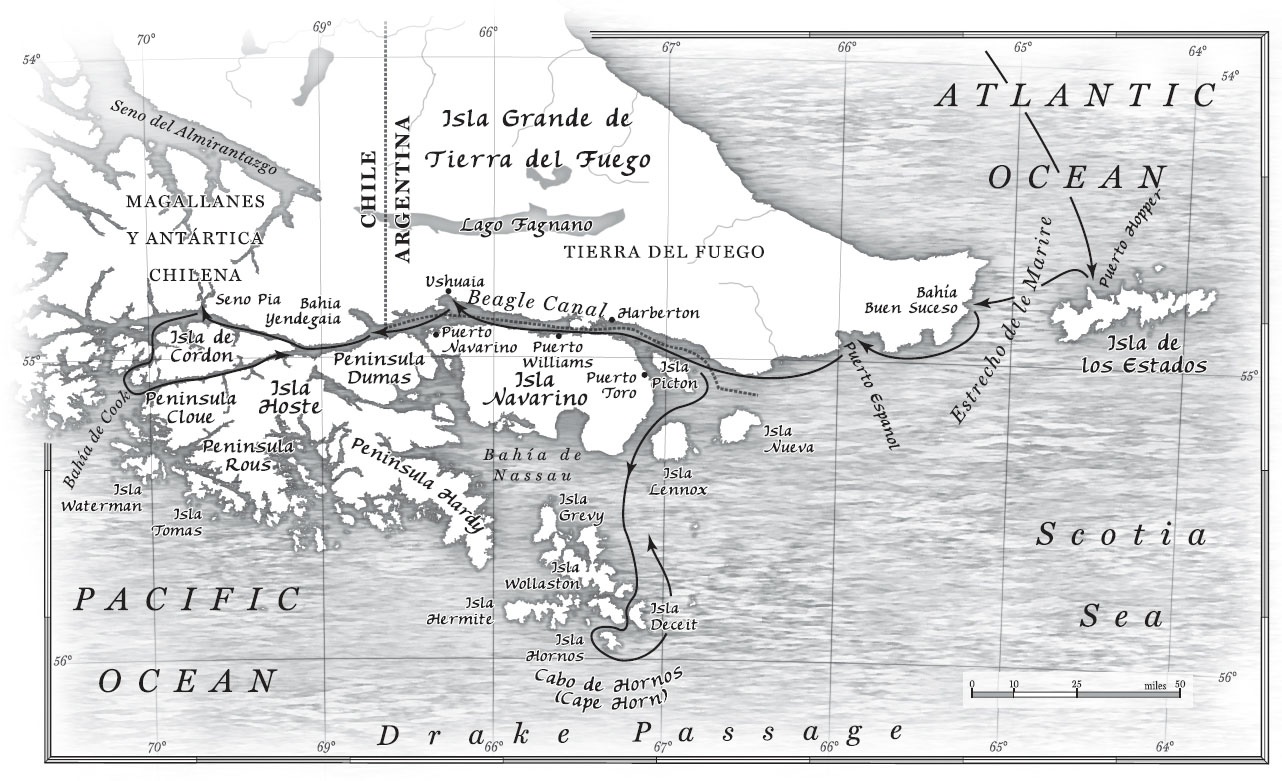

I have made two of my lifes toughest voyages in the past few years: one I had always wanted to make, and the other I would have given anything to avoid. Both involved letting go of one world, and finding the courage to live in the next. One is the long trek, under sail, to one of the most profoundly remote parts of the world; to an often bleak land of rock, ice and near overwhelming storms these are the waters of the infamous Cape Horn. The other is the long, hard journey through the death of my son, Nicholas, who took his own life at the age of twenty-three; to travel this road is to suffer desolation that no earthly place can inflict upon you. The two journeys are not unconnected; they are both tales of high adventure and discovery through some of lifes most difficult landscapes, and both begin, as all voyages must, with finding the courage to face the future, reserving the past as a fond memory and not something you should cling to like a drowning soul. Your strength must come from what lies ahead. That is true voyaging.

Our first night at sea, the first after leaving England, had been kind to my wife, Libby, and me. Our boat, Wild Song, felt sure-footed as she made her way south in a following wind. She rolled and creaked in ways that were new to us, having owned her for only one full season, but already she was feeling like a friend. You need to be able to trust your boat for then, in return, she will grow into an extension of yourself, and already I felt a bond forming between us. By dawn we were abreast Ushant, the rocky, low island that is the far north-western fingertip of mainland Europe. Released now from home waters, spat out of the English Channel, we were now pointing our bows ever southward towards the Bay of Biscay, aiming for the island of Madeira a few hundred miles to the south-west of Portugal.

This was the first leg of a voyage to an uncertain place, in all senses, although it is true that already forming in my mind was the ultimate trophy, to sail around Cape Horn. There can be hardly a sailor who has not imagined what this place of grim reputation must be like, yet at the same time wanted to experience its wickedness for themselves. It is spoken of as an Everest. But how I might get there, and what I would do next if I ever achieved that, was far from decided.

From the moment when I first pulled out the charts to plot our course across the Bay of Biscay, I realised that without hardly any deviation we would pass close to an unmarked and unremarkable spot in the middle. It is defined only by imaginary lines of latitude and longitude, and is of no significance to anyone other than ourselves. It is 46.16N, 7.12W.