The RSPB is the countrys largest nature conservation charity, inspiring everyone to give nature a home so that birds and wildlife can thrive again.

By buying this book you are helping to fund The RSPBs conservation work.

If you would like to know more about The RSPB, visit the website at www.rspb.org.uk or write to: The RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL; 01767 680551.

First published in 2014

This electronic edition published in 2014 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright 2014 text by Nicola Chester

Copyright 2010 photographs as credited on

The right of Nicola Chester to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010

www.bloomsbury.com

www.bloomsburyusa.com

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New Delhi, New York and Sydney

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for

Commissioning editor: Julie Bailey

Project editor: Alice Ward

Series design and layout: Rod Teasdale

ISBN (Ebook) 978-1-4729-0387-7

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters here.

Bloomsbury is a trade mark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Contents

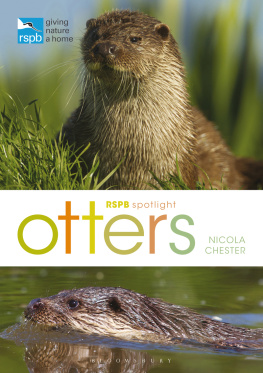

Seeing a wild otter is thrilling, but their presence also indicates an environment healthy enough to give life support to a whole ecosystem.

Otters are among the most exciting and elusive mammals living alongside us today. They are agile, intelligent and playful, and many of us dream of seeing one in the wild. Otters are so well adapted to their environment that when they enter the water they simply pour themselves in, soundlessly melting away and becoming part of the river or sea itself another ripple in the current or a chain of bubbles bursting on the surface.

Our name for these elemental creatures has evolved from our old word wodr, from which we also get the word water, hinting at a time when Otters were more prevalent (though no more conspicuous), and when their sinuous slip of a spirit seemed indistinguishable from the element of water itself. They are almost mythical, and made more exciting because of course they are not. Yet often all you see for proof that they exist are hints, signs that they have been there: a half-eaten fish on the riverbank, a sweet-smelling, fishy poo or pawprints like little sunrays in the silty beach at a bend of a river.

As a predator at the very top of a food chain, the Otter was never numerous, but its presence or the hint of its presence (the merest sign one has passed through) is the Holy Grail of river conservation, the gold stamp indicating the health of a river and all that lives in and around it. An Otter in the water produces a skip-a-heartbeat moment of joy for any conservationist, and a hint that we may be getting things right in living with nature.

Elusive, lithe, playful, and able to shift so effortlessly from land to water, Otters cast a spell of an elemental kind.

Water dogs

Our Otter is the Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) and the only otter species found in Britain and continental Europe. It is also known as the European River Otter and the Old World Otter. Otters are secretive, mostly nocturnal and semi-aquatic they are never far from a source of water. They are sleek, lithe, streamlined animals with an exuberance about them that suggests boundless energy. All members of the otter family are dark chocolate-brown, often with a pale creamy chin, throat and belly. They have bright, intelligent eyes, small ears and lots of marvellous, highly sensitive whiskers.

An exuberant leap into the Little Ouse, Norfolk: perfectly streamlined and adapted for life in water, Otters are never far from it and seem to revel in their swimming and diving ability.

Otters belong to the Mustelidae or weasel family of carnivorous (meat-eating) mammals. Like all mustelids, they are long-bodied with short, powerful legs, and feet with five clawed toes. However, unlike other mustelids, Otters have webbed feet and long, thick, muscular tails both of these attributes help them move efficiently through the water.

Otters are surprisingly large, at over a metre (3ft) from the nose to the tip of the Labrador-like tail, and they are often described as dog-like. Male Otters are in fact known as dogs and females as bitches. Although their young are known as cubs, they often get called pups or even kits, but never puppies. In Welsh they are called dr-gi, which means water dog, and in Scottish Gaelic, matadh, meaning hound. In the Irish language they are called dobhar-ch, which again means water dog.

The only serious swimmer in the family of British mustelids; webs of skin stretch between the Otters five claws, helping to propel it through the water.

With fluid lines and such a long, low profile, otters can melt from land into water with barely a sound or a ripple.

An Otter swims low in the water, with just its eyes, nostrils and the top of its broad, flat head and part of its long back visible. Its tapering, muscular tail acts like a rudder and can be half the length of its body. When an Otter is cruising along, its partly submerged head can make it look a little like a swimming Border Terrier, but Otters also dive and break the surface of the water in the manner of dolphins, arching their backs and lifting their tails yet slipping beneath the water with barely a splash. Sometimes their presence underwater is only revealed by a glimpse of a tail or a line of bubbles rising to the surface of the water. Swimming Otters can be confused with Mink, animals you are probably more likely to see. But at about half the size of Otters, mink are much smaller, and they are fluffier, more buoyant in the water and have very pointy, ferret-like faces.

On land Otters really can look like dogs and will bound along the waters edge or across roads between habitats with a hump-backed gambol. When they are wet they look black and their fur is spiky. Like other mustelids, Otters can stand up straight on their hind legs, balancing on their long back feet and tail, forepaws hanging down like (unrelated) Meerkats, to look around.