HUMAN IMPACTS on SEALS, SEA LIONS, and SEA OTTERS

HUMAN IMPACTS

on SEALS, SEA LIONS,

and SEA OTTERS

Integrating Archaeology and

Ecology in the Northeast Pacific

Edited by

Todd J. Braje and Torben C. Rick

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu .

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2011 by the Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Human impacts on seals, sea lions, and sea otters : integrating archaeology and ecology in the Northeast Pacific / edited by Todd J. Braje and Torben C. Rick.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-26726-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Marine mammal remains (Archaeology)Northwest Coast of North America. 2. Seals (AnimalsEffect of human beings onNorthwest Coast of North AmericaHistory 3. Sea otterEffect of human beings onNorthwest Coast of North AmericaHistory. 4. Hunting, PrehistoricNorthwest Coast of North America. 5. PaleoecologyNorthwest Coast of North America. I. Braje, Todd J., 1976 II. Rick, Torben C.

CC79.5.M35H86 2010

930.1dc22

2010034645

Manufactured in the United States of America

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

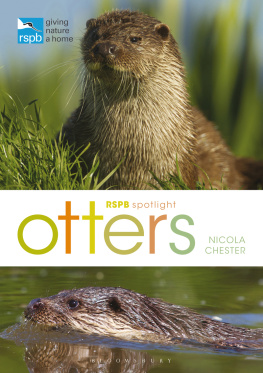

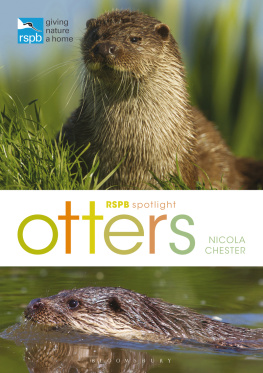

Cover image: View of St. Paul Island by Louis Choris, from Voyage Pittoresque Autour du Monde (1822). Alaska State Library, Louis Choris, Photograph Collection ().

CONTENTS

CONTRIBUTORS

MATTHEW W. BETTS

Canadian Museum of Civilization

Gatineau, Quebec, Canada

TODD J. BRAJE

San Diego State University

San Diego, California

SUSAN J. CROCKFORD

Pacific Identifications, Inc.

Victoria, BC, Canada

BRENDAN J. CULLETON

University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon

ROBERT L. DELONG

Alaska Fisheries Service Center

Seattle, Washington

JON M. ERLANDSON

University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon

S. GAY FREDERICK

Pacific Identifications, Inc.

Victoria, BC, Canada

DIANE GIFFORD-GONZALEZ

University of California, Santa Cruz

Santa Cruz, California

WILLIAM R. HILDEBRANDT

Far Western

Davis, California

ERICA HILL

University of Alaska Southeast

Juneau, Alaska

TERRY L. JONES

California Polytechnic State University

San Luis Obispo, California

SHAWN LARSON

Seattle Aquarium

Seattle, Washington

VERONICA LECH

Idaho State University

Pocatello, Idaho

ROBERT J. LOSEY

University of Alberta

Edmonton, AB, Canada

R. LEE LYMAN

University of Missouri

Columbia, Missouri

HERBERT D.G. MASCHNER

Idaho State Unversity

Pocatello, Idaho

IAIN MCKECHNIE

University of British Columbia

Vancouver, BC, Canada

SARAH MELLINGER

University of California, Santa Barbara

Santa Barbara, California

MADONNA L. MOSS

University of Oregon

Eugene, Oregon

JUDITH F. PORCASI

University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California

TORBEN C. RICK

Smithsonian Institution

Washington, D.C.

ADRIAN R. WHITAKER

Far Western

Davis, California

REBECCA J. WIGEN

Pacific Identifications, Inc.

Victoria, BC, Canada

1

People, Pinnipeds, and Sea Otters of the Northeast Pacific

Torben C. Rick, Todd J. Braje, and Robert L. DeLong

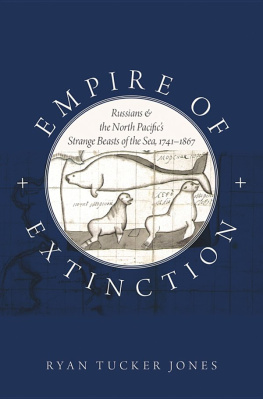

MARINE MAMMALS, SUCH AS polar bears, sea otters, seals, sea lions, and walruses, are an extraordinary group of organisms, many of which maintain a link to both aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Often highly intelligent with sophisticated communication systems, marine mammals are a fundamental component of marine ecosystems around the world (Berta et al. 2005; Riedman 1990). Human interaction with seals, sea otters, and other marine mammals spans millennia and the entire globe (Erlandson 2001; Etnier 2007; Hildebrandt and Jones 1992; Klein and Cruz-Uribe 1996; Lyman 1995; McNiven and Beddingfeld 2008; Monks 2005a; Nagaoka 2002; Stringer et al. 2008). Containing large amounts of meat, oil, ivory, and other important raw material and dietary resources, pinnipeds (seals, sea lions, and walruses) and sea otters have been hunted and scavenged by people in the northeastern Pacific for much of the Holocene or earlier (Braje 2010; Broughton 1994, 1999; Burton et al. 2001, 2002; Colten 2002; Corbett et al. 2008; Crockford and Frederick 2007; Domning et al. 2007; Erlandson al. 2005; Etnier 2002a, 2002b, 2004, 2007; Gifford-Gonzalez et al. 2005; Hildebrandt and Jones 1992, 2002; Jones and Hildebrandt 1995; Lyman 1991, 1995, 2003; Moss et al. 2006; Newsome et al. 2007; Porcasi et al. 2000; Rick et al. 2009). The large terrestrial breeding colonies of some pinnipeds have made them highly susceptible to human hunting in the distant and near past. During the fur and oil trade of the 18th and 19th centuries, for example, human hunting of pinnipeds and sea otters decimated marine mammal populations, causing the extirpation of local populations of sea otters (Enhydra lutris), Guadalupe fur seals (Arctocephalus townsendi), and northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) and the extinction of the Stellers sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas; Ellis 2003; Ogden 1941; Scammon 1968). Archaeological data demonstrate that human impacts on marine mammals in the more distant past were also substantial and suggest that much remains to be learned about the prehistory of these animals.

With the recognition that human occupation of the worlds coastlines has great time depth (Bailey 2004; Erlandson 2001), research on ancient human impacts and influences on the biogeography, behavior, and ecology of pinnipeds, sea otters, and other marine organisms has increased. The shifting baselines phenomenon (Pauly 1995)the notion that modern and historical ecosystems have been fundamentally altered by humans and that ecological baselines or benchmarks change dramatically over timehas prompted researchers from a variety of disciplines to emphasize the importance of archaeological and historical data in the management and restoration of marine ecosystems around the world (Erlandson and Rick 2010; Jackson et al. 2001; Pinnegar and Engle-hard 2008; Rick and Erlandson 2008). Faunal remains found in archaeological sites contain vast amounts of information on the composition, biogeography, and abundance of animals that were present in the past, as well as changing climatic conditions, human subsistence practices, and similarities and differences with the present day (see Lyman 2006; Lyman and Cannon 2004). Although the potential of these data remains underexplored, several recent studies have demonstrated the utility of archaeology for informing contemporary conservation issues, including the historical ecology of seals, sea lions, and sea otters (Lyman 2003; Etnier 2004, 2007; Hildebrandt and Jones 2002; Newsome et al. 2007; Rick et al. 2009).

Next page