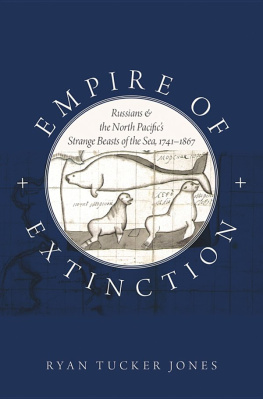

Empire of Extinction

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Oxford University Press 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, Ryan Tucker, author.

Empire of extinction : Russians and the North Pacifics strange beasts of the sea, 17411867 / Ryan Tucker Jones.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780199343416 (hardback)

eISBN 9780199373802

1. Extinct animalsNorth Pacific Region. 2. Stellers sea cow Effect of human beings onNorth Pacific Ocean. 3. Fur tradeNorth Pacific Region. 4. NatureEffect of human beings onNorth Pacific RegionHistory. 5. Natural historyNorth Pacific Region. 6. North Pacific Region ColonizationEnvironmental aspects. 7. North Pacific OceanEnvironmental conditions. 8. RussiaColoniesNorth Pacific Region. I. Title.

QL88.15.N69J66 2014

591.68091823dc23

2013047262

To my father, Helmuth Jones, and my grandfather, the late Everett Jones.

They inspired this work in many ways, by teaching me the value of history, the pleasure of hard work, the importance of travel, and the locations of home.

CONTENTS

The trajectory of researching and writing this book mirrored, in some ways, that of its subject. I began studying the history of the Russian Empire while living in New York City. In 2005, I moved to St. Petersburg, Russia, to conduct research. After freezing through one of the citys coldest winters in recent history, it became clear that I needed to experience firsthand the empires furthest reaches. In the early summer of 2006, I spent a month in Siberia and Kamchatka, exiting the archives and moving into the fields and mountains. That experience convinced me I had chosen the right subject; the lands and seas I had previously encountered only in old documents came alive before my eyes, and forever changed me with their beauty and wildness. The following year, I went to Kodiak Island, and with two old friends kayaked among whales and sea otters, camping on some of the loneliest shores in North America. While I was revising my dissertation, my father traveled with me to Sitka and Unalaskathe latter being a place where both of my grandfathers spent part of World War II. Last year, as I finished this manuscript, my beautiful wife joined me on the pilgrimage of St. Herman on Spruce Island, in Alaska. There we received the generous hospitality of the Alutiit, who shared their stories and their salmon. At some point, I realized that, while the Russians had left the Pacific and gone back to Europe, I had come home.

The debts incurred along this path are enormous. David Armitage taught me to be an historian, helped me to think big, and opened innumerable doors I hardly knew existed. He has been both a mentor and friend for the last nine years. John McNeill introduced me to the field of environmental history, and made it so exciting that I still cannot imagine writing about anything else. Richard Wortman instructed me in the nuts and bolts of Russian imperial history, and steered me clear of the big mistakes. Doug Weiner did a little of all of the above, while also giving generously of his immense knowledge of Russian environmental history.

In St. Petersburg, Tatiana Fedorovna at the Russian State Archive of the Navy saved this book by generously taking time to introduce me to eighteenth-century Russian handwriting. She is a shining example of the best side of Russian archival culture. In the United States, Anastasia Tarmann-Lynch at the Alaska State Library provided invaluable guidance, suggestions, and ideas. Her colleagues there also deserves thanks, as do librarians and archivists at the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences Archive, the Russian State Historical Archive, the Krasheninnikov Library in Kamchatka, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, the John Carter Brown Library, the Bancroft Library at the University of California Berkeley, and the University of Washington Special Collections. At Oxford University Press, Susan Ferber has continually streamlined my prose; I wish she had been there from the start. The publishers anonymous readers also sharpened my arguments and gave the book new directions.

Along the way, this book has also benefitted from generous financial support. The Fulbright Program funded research in St. Petersburg and Moscow, and the American Council of Learned Societies provided support during the writing process. Appalachian State University and Idaho State University both contributed travel and research support at various points along the way. The Alaska Historical Society both alerted me to the importance of local history and kindly awarded me a travel fellowship to present my research in Unalaska. Many thanks to all.

Less tangibly, but just as importantly, a number of friends and colleagues have given support and intelligence. At Columbia University, Jason Governale, Kevin Murphy, and Giovanni Ruffini shared expertise and sometimes loaned spare couches. In Russia (and beyond), Stephen Brain inspired me with his archival tenacity and environmental acumen. Julia Lajus has been a warm friend and facilitator in St. Petersburg and in many unlikely parts of the world, from Kolding to Perth. At Appalachian State University, Ed Behrend-Martinez and Judkin Browning initiated me into a different kind of foreign culture and helped me navigate the early stages of book contracts. My excellent department at Idaho State University, and in particular Kevin Marsh, has given me more support and encouragement than I could have ever expected. In Alaska, Jenya Anichenko and Jason Rogers linked me much more directly to the places (and boats) I write about in this book. Katherine Arndt, at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, shared with me her unrivaled knowledge of Russian Americas primary sources. Along the way, at multiple points and places, I was also fortunate to become friends with Ilya Vinkovetsky and Andrei Znamenski.

When I began this research, I was living by myself in a small apartment on 113th Street in Manhattan. While the housing space remains small, it is now filled with the wonderful, ever-supportive Hannah Cutting-Jones and the ever-wonderful and sometimes supportive Genevieve and Everett. Hannah read every chapter of this book at various stages, providing the eye for detail and sense of style I often lack. Though she came to this book halfway through its creation, she is its Katharine the Great. Thank you, beyond measure, for coming with me to St. Petersburg, Trier, Alaska, and places even more remote. My mother, Janie Jones, also helped nourish this book. She was with me the first time I saw Russia and her house was always my second library. Though Im sure she wishes I had chosen a warmer field of research, it meant a lot to me, and to this book, that she always supported me.