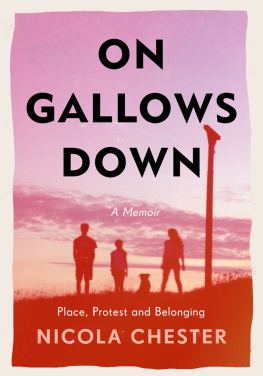

Praise for On Gallows Down

From treetop protests at the Newbury Bypass to the grand Highclere Estate, On Gallows Down is that rare thing: nature writing as political as it is personal.

Melissa Harrison , author of The Stubborn Light of Things: A Nature Diary

A powerful personal and political journey through place that charts the profound influence we have on nature, and that nature has on us.

Rob Cowen , author of Common Ground and The Heeding

An evocative and inspiring memoir which touches on environmental protest, family, motherhood and, most importantly, nature. Her passion for the natural world and especially birds, shines through in this wonderful book.

Claire Fuller , author of Unsettled Ground

Nicola Chester deserves many readers. On Gallows Down is an impassioned study of a contested landscape, which interrogates our attitudes towards land stewardship, ownership and living in the right relationship with both human and other-than-human neighbours. Charged with love and fire, On Gallows Down is a beautiful exploration of a much-mapped, multi-faceted landscape.

Katharine Norbury , author of The Fish Ladder

Chesters writing has a lovely elasticity, dancing between wonder, introspection and anger as she moves from the particular to the universalShe belongs to the disappearing English, rural working class, and is intent on handing this baton to her three children, who play a part in the book. Chester also explores the familiar tension between wanting to write and being needed at home. The heady ecstasy of time carved out alone, in nature. The scrabble to earn a precarious living, and the insecurities of occupying a tied cottage. The idea of home lies at the heart of this fierce, beautifully written, immersive book about ones place within the landscape.

Tessa Boase , author of Etta Lemon: The Woman Who Saved the Birds

Nicolas passionate and enduring love of nature shines through every single word, paragraph and page of this book, as she seamlessly weaves memoir with stories of the landscape in which she is so deeply rooted that it seems to speak through her. Powerful, enlightening, dazzling, hopeful, On Gallows Down is a rare and precious gem - to be savoured, not rushed, and returned to again and again. My words cannot do this book justice - it simply needs to be read.

Brigit Strawbridge Howard , author of the Wainwright-shortlisted Dancing with Bees

Also by Nicola Chester

RSPB Spotlight: Otters (Bloomsbury, 2014)

ON

GALLOWS

DOWN

Place, Protest and Belonging

Nicola Chester

Chelsea Green Publishing

White River Junction, Vermont

London, UK

Copyright 2021 by Nicola Chester.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form

by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Developmental Editor: Muna Reyal

Project Manager: Alexander Bullett

Copy Editor: Caroline West

Proofreader: Laura Jorstad

Designer: Melissa Jacobson

Printed in the United Kingdom.

First printing September 2021.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 21 22 23 24 25

ISBN: 978-1-64502-116-2

Chelsea Green Publishing

85 North Main Street, Suite 120

White River Junction, Vermont USA

Somerset House

London, UK

www.chelseagreen.com

For the flock, feather, nest and homecoming that is my family.

To Martin, who saved me

from the man on the big white horse,

and to our children

Billy, Evie and Rosie

and the hill that raised them.

There are some heights in Wessex, shaped as if by a kindly hand For thinking, dreaming, dying on, and at crises when I stand, Say, on Ingpen Beacon eastward, or on Wylls-Neck westwardly, I seem where I was before my birth, and after death may be.

Thomas Hardy, Wessex Heights from Satires of Circumstance: Lyrics and Reveries

The place we occupy seems all the world

John Clare, The Shepherds Almost Wonder Where They Dwell

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

Bird in a Landscape

It is St Georges Day, late April, two days shy of my birthday. The sky is the colour of a pheasants egg and skylarks are singing against it at such a height I cant see them. A just-discernible shimmer of heat blurs the near horizon of orange gravel that marks the old runway of this former US airbase. I am sitting on my hands on top of an old American fire hydrant, its once-smooth sides speckled with rust and yellow and red paint curled and crusted like lichen. I cant quite reach the ground and sit swinging my legs, a toe occasionally reaching a knobbly chunk of flint to kick away. I think Ive been stood up.

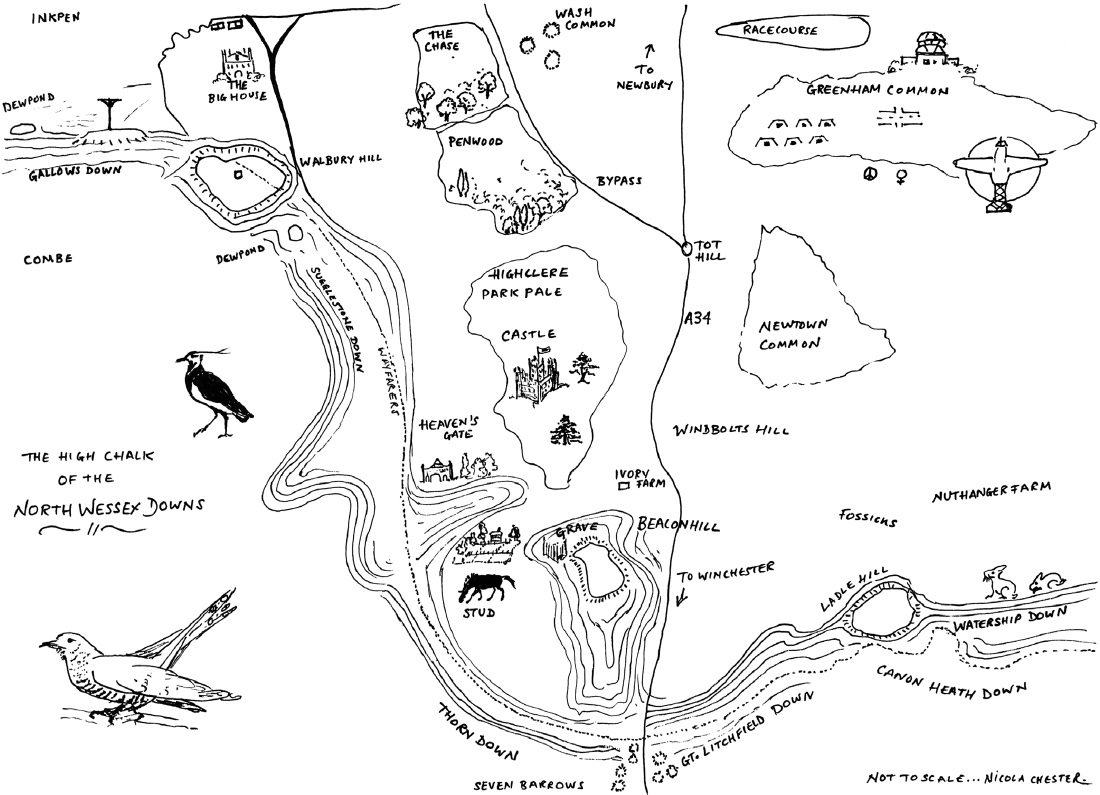

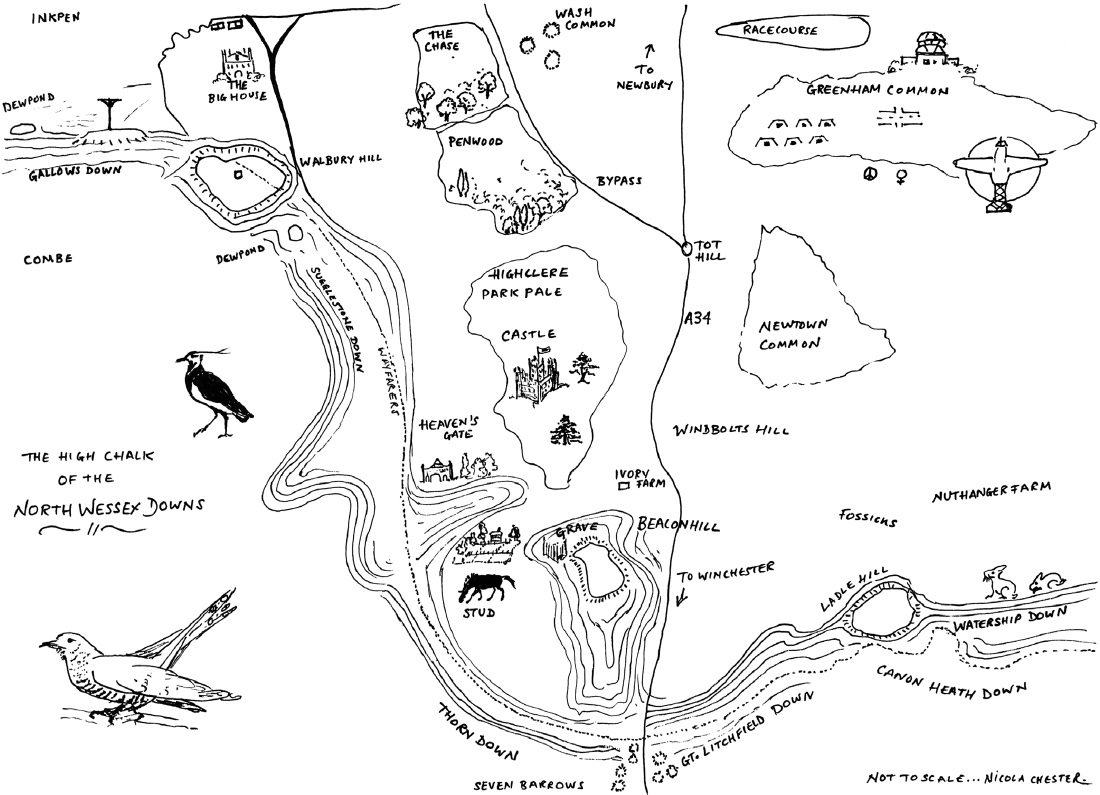

The view to the southwest is all curves. The open-mouthed caves of the old cruise-missile bunkers replicate the smooth, lyrical, whaleback arc of the chalk hills beyond and their ancient procession of round and long barrows and hillforts. The striking green contours of bare, richly flowered and springy turf take in White Hill, Watership Down, Ladle Hill and Great Litchfield Down. On the other side of the hidden A34 are the elephant graves of Seven Barrows on the Highclere Estate where British aviation pioneer Geoffrey de Havilland made his first flight in a homemade aeroplane in 1909. Above Seven Barrows is the graceful dome of Beacon Hill, crowned with its Iron Age hillfort. At its centre lie the railings and grave of the (reputedly mummified) 5th Earl of Carnarvon, co-discoverer of the tomb of the Egyptian boy pharaoh, Tutankhamun. Only from that hill can I see the old, isolated, flint-and-brick estate cottage at Highclere that was once my home. I still have the key to its blue-liveried front door on a piece of matching ribbon by the side of my bed. I like to weigh its cool heaviness in my hand and for my fingers to remember the satisfying grate it made when turned in a lock the size of a childs shoebox. From there, the hills roll on to where I live now, within an afternoons walk along the ridgeway.

If I lower my gaze again to the foreground, the old bunkers, built to hold nuclear warheads as well as withstand a strike from one, are now long-haired, softened relics that have become a part of the narrative-landscape of this place. Steep-sided, flat-roofed, grassed all over, they seem part Neolithic long barrow, part natural chalk downland; half-built pyramids for a pharaoh or shallower versions of the prehistoric flat-topped cone of Silbury Hill not many miles from here. Their doorless entrances are wide mouths, open and raised obediently to the sky, all six singing the same long note: say ahhh. They are empty vessels, waiting for a spoonful of something.

I am sitting in the middle of what was formerly RAF Greenham Common, a military airbase in West Berkshire, Southern England, a few miles south of the town of Newbury. Now just Greenham Common, it is being restored to what it had been for thousands of years - a thousand acres of open heath on a gravel table, with wet, wooded, primeval gullies that run off it like creases in a tablecloth. Greenham Common, almost as I know it, was created millennia ago, when the little, benign chalk streams of the Kennet and the Enborne - which gave my schoolhouses two of their names - were mighty rivers that washed out the flints from chalky subsoil overlying sunset-coloured clays and sands.

Greenham Common is a place of big skies and wide, cloud-reflecting pools. The joyful sense of freedom and open space I felt 21 years ago when the fences came down is renewed every time I come back. Back then, that feeling had a lot to do with the Commons military and social history, its place in local culture and how I remembered it before the fences as a child. Yet now, that sense has become permanent, emanating from the place itself like an excitable shiver of heat haze on the low horizon. A force of nature. This high, wild, gravelly plateau, romantically bleak one day and a riot of crackling warmth and colour on another, is our own wild moor. Richard Mabey, the father of modern writing on nature, wrote about Greenham Common in 1993 when it was decommissioned and up for sale: It will be heartwarming if the place can become a common ground for humans as well as wildlifea powerful symbolcomplete with grazing animals, ponds and a few rusting relics to remind future generations of what this place once was. The sense of happy incredulity that this actually came to pass does not diminish.