BLOOMSBURY WILDLIFE

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

This electronic edition published in 2019 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY WILDLIFE and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in United Kingdom 2019

Copyright Jules Howard, 2019

Copyright 2019 photographs and illustrations as credited

Jules Howard has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5581-4 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5582-1 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5583-8 (ePDF)

Design by Rod Teasdale

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

For all items sold, Bloomsbury Publishing will donate a minimum of 2% of the publishers receipts from sales of licensed titles to RSPB Sales Ltd, the trading subsidiary of the RSPB. Subsequent sellers of this book are not commercial participators for the purpose of Part II of the Charities Act 1992.

Contents

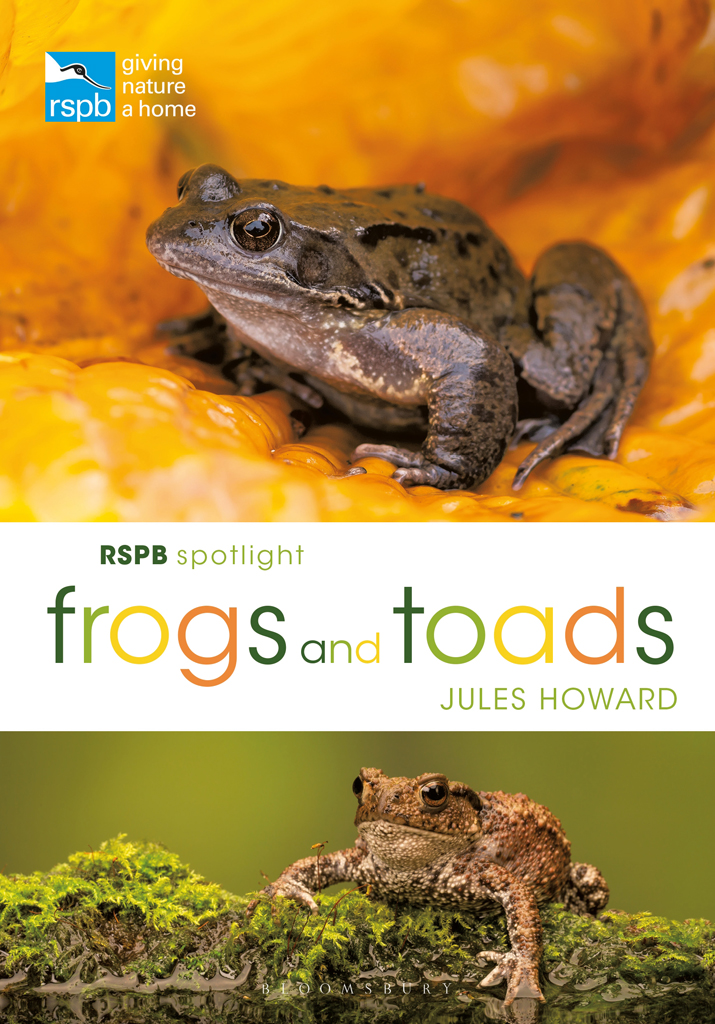

Amphibian Apparel

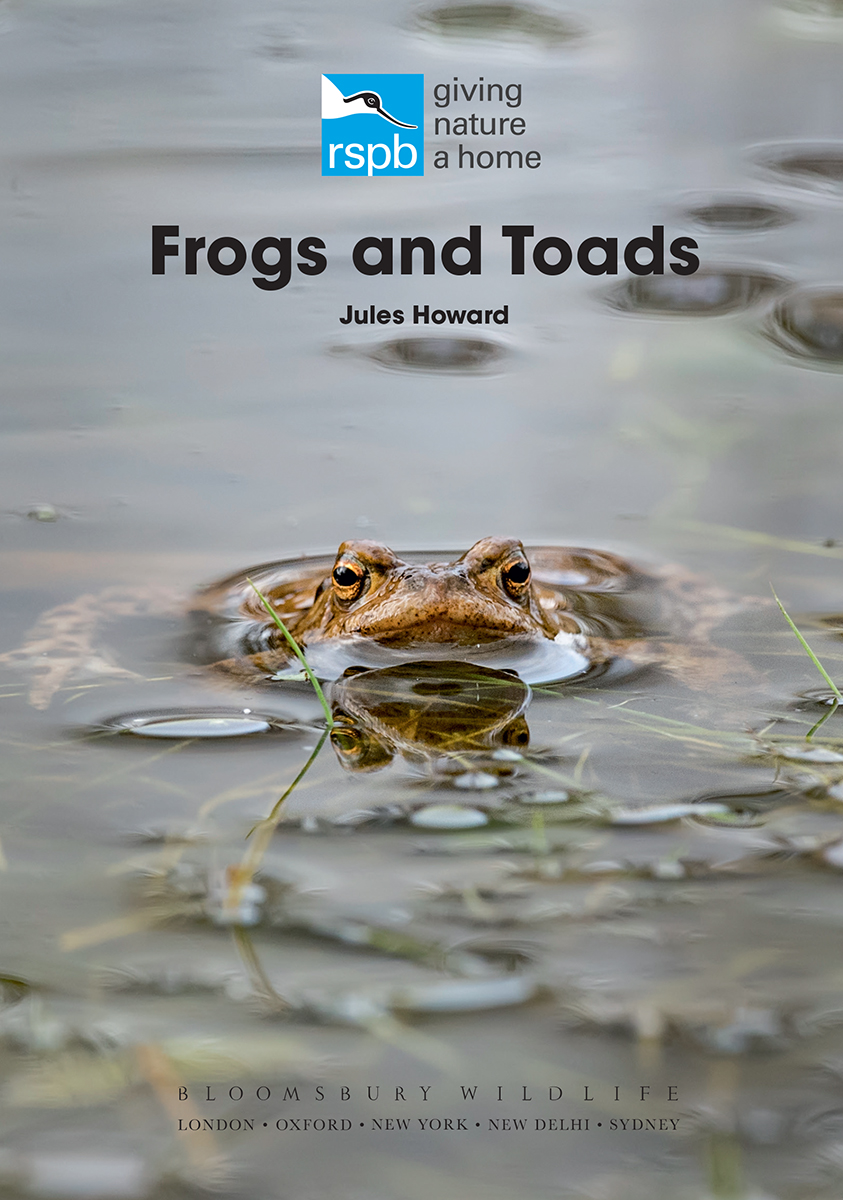

You would be hard pushed to design from scratch an animal seemingly so weird as a frog or toad. Look more closely, however, and you will discover a story written in fossils that charts the rise of a group of animals that hit upon a shape and style almost perfect for dodging the interests of monstrous predators, yet that are themselves the stuff of nightmares for the invertebrate prey on which they thrive.

Mastering two domains, both water and land, means amphibians can take advantage of twice the ecological space in a single lifetime.

With their sticky tongues, bulbous eyes, madcap leaps and spectacular metamorphosis from tadpole into adulthood, amphibians sound like something dreamed up by a sugar-addled six-year-old. Shine a spotlight on these creatures, however, and a far more subtle and engaging reality emerges. There is real beauty in frogs and toads, but it is not a beauty you may ever have considered. And so, if I have one aim in this book, it is that you might come to view Britains handful of frog and toad species in a new light. What we lack in the number of amphibian species we more than make up for in interesting stories of ecological endeavour and charismatic grace.

So, turn the pages that follow. Together, we will become more acquainted with the UKs frogs and toads and their unusual modes of life. And perhaps we will see it in our hearts to engage further with their conservation. For, as we will discover, the fate of frogs and toads across the world is far from secure, and these threats apply in the UK as much as anywhere else. But there is plenty to offer us hope, not least a vibrant conservation scene, citizen science at its best and a public that really cares. And amphibians have great persistence and survival in their blood. Perhaps, therefore, they have something to teach us.

Both frogs and toads have evolved in a world of large wetland predators. All species have large, sensitive eyes and are ever-watchful of threats.

Family relations

Where did frogs and toads spring from? And what, if any, is their family relationship? Frogs and toads both belong in the order of tailless amphibians called Anura, or the anurans, literally meaning without tail. The first fossil anurans amphibians with distinctive long leg bones, a three-pronged pelvis and a highly reduced tail come from the Jurassic Period, dating back approximately 180 million years. Although it is tempting to consider those early creatures as primitive, not much further evolved than the early land-fish that first walked the Earth 370 million years ago, they were apparently proficient in all sorts of ways. Highly adaptable, quick to branch into new species and with long legs able to foil a host of predatory attacks, the earliest anurans hit upon a shape that would allow them to prosper throughout the Jurassic and into the Cretaceous Period while other species around them died out.

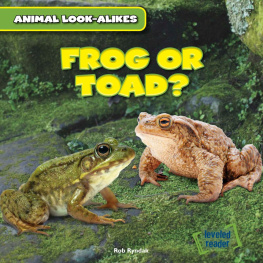

So, what is the difference between frogs and toads? Scientifically speaking, true toads are members of Bufonidae, or the bufonids, one family among 47 others that are placed within the order Anura. If this sounds curious to you, welcome to the occasionally confusing nature of taxonomy! Even more confusingly, there are amphibians we commonly call toads, like the European Common Midwife Toad (Alytes obstetricians), that are not true toads at all. In Britain, luckily, both our toad species the Common Toad (Bufo bufo) and Natterjack Toad (Epidalea calamita) are true toads. For the purposes of this book, therefore, which focuses on UK species, the term toad is used to refer to true toads only, while frog is used to refer to all other anurans.

The Natterjack Toad a true toad because it belongs to the bufonid branch of the frog family tree.

The Age of the Anurans

The question of when toads sprouted from the anuran family tree has become a hot topic of debate, but many consider today that they probably evolved in the Cretaceous Period (14565 million years ago) in what is now South America or, intriguingly, a once ice-less Antarctica. In the millions of years that followed, as the land split apart and merged into the vast continents we know today, toads continued to diversify and formed new branching groups, each riding its given continent like a lifeboat. For this reason, many toad species today often occur over wide continental areas. The Common Toad, for instance, isnt just a British species; it has a distribution that stretches from the UK in the west, to Asia in the east and North Africa in the south. Not bad for a creature with little by way of speed, you might think.