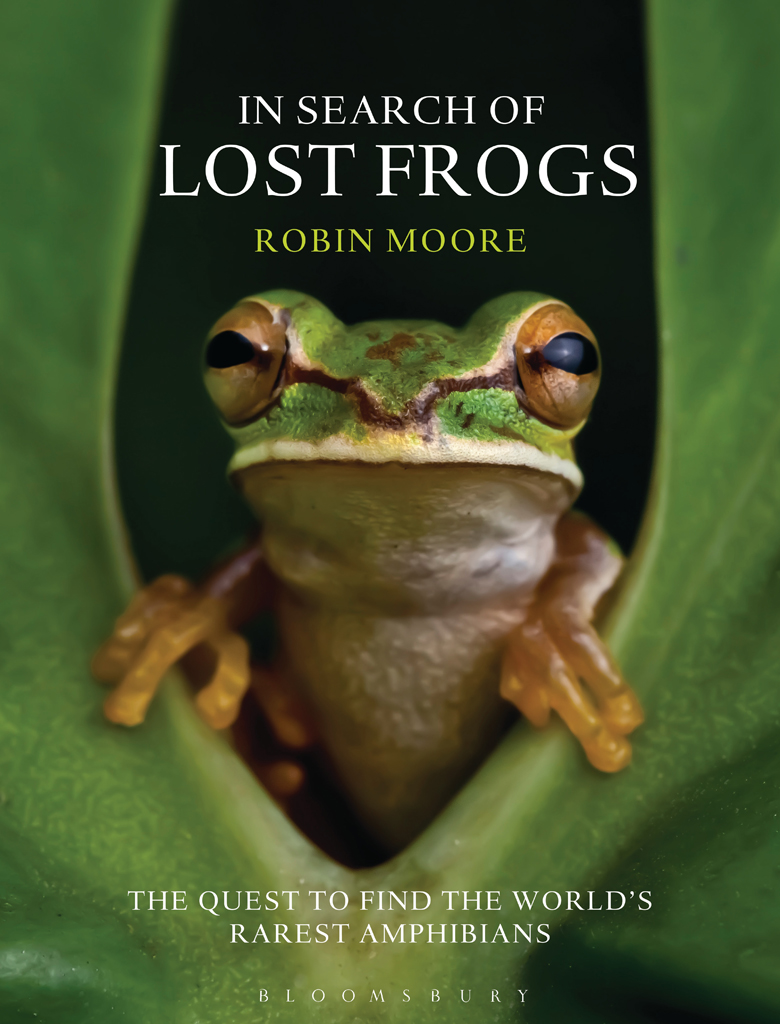

FOREWORD

Comedy writers are supposed to be cynics. Were meant to squint at lifes ragged parade with a sardonic eye, as we satirise human folly.

I was in California writing for The Simpsons satirising away, squinting and sneering at one and all. My guiding principles? Life is ridiculous; people never learn; lets have a few laughs before it all goes KABLAM! Then I met Robin Moore.

Robin was young and energetic and bafflingly free of cynicism. His passion was to protect the rare and gemlike frogs of the world from disappearing forever. Not only was he going to hurl his entire life at this quixotic mission; he fully expected to succeed.

What was wrong with this guy?

Didnt he know that people are selfish, materialistic, shortsighted and rapacious? Didnt he know that laptops and smartphones suck up all our time now, leaving nature tapping at the window like an old forgotten boxcar tramp?

Sure. Robin knows what hes up against. But hes also resourceful, and tenacious, and he has allies. Millions around the world Im one of them have an enduring crush on frogs and toads and salamanders. We can safeguard these captivating critters and revel in their pursuit of hoppiness.

I know we can do it, because one night I rode in one of those funky cars thats shaped like a cube. Its owner proudly showed me the illuminated cup holder, which lit up in seven blazing colors. At that moment I thought, Human beings are WIZARDS!

This book will dazzle you with the elegance and allure of amphibians. After that, if you want to help us conserve these charmers, splash on in!

GEORGE MEYER

Seattle

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

On a late September day in 2007, three miles above the equator in southern Ecuador, I joined a team of scientists on a quest to find a small black frog. We hiked across windswept peaks under cotton-wool clouds billowing in a sapphire sky the air so thin that it made my head pound and my lungs ache in search of a creature no bigger than my thumb. The frog had not been seen in two decades; its disappearance had been as sudden as it was mysterious. The frog was posthumously named after the Quechua word for sadness, to lament the loss of frogs from cool streams and glassy pools across South America and beyond. It was my first search for a lost frog, but just one step of a bigger journey.

The following year in the shallows downstream I saw my first corpse. She was also a harlequin frog, but a different kind with brilliant yellow on black, she was as beautiful in death as in life. Her stillness was broken only by the rhythmic wash of water on splayed limbs, and onto her back clung a male oblivious to her passing trying to mate. They were among the last of a species new to science. As her rigid limbs were squeezed into a jar filled with frogs like pickled eggs back at the lab in Quito, she took her place in a growing queue of species to be named and mourned. Her companion would join her just weeks later; both of their lives taken by a silent killer that was on the move, from Costa Rica to Ecuador and Australia to California.

The slow tug of nostalgia for lost amphibians punctuated by jolts of grief at the sight of dead frogs transformed a childhood passion, nurtured in the peat bogs of the Scottish highlands, into a global quest to unravel one of the most compelling mysteries of our time: what was happening to the amphibians?

My quest led me in 2010 to spearhead an unprecedented coordinated and global search for frogs, salamanders and the lesser-known caecilians. Over six months more than a hundred biologists slashed through thick jungle, waded up rivers and hiked remote mountain passes, from Borneo to Brazil, Colombia to Congo and Israel to India, faced with long odds and often miserable conditions and armed with boots, headlamps and dogged determination to find some of the most elusive creatures on earth. I was lucky enough to join some of these searches, to feel the pangs of disappointment and the thrill of discovery in some of the most remote and uncharted corners of the world.

On the following pages I invite you to join me on my journey as it unfolds in three parts. It begins in the back gardens and remote moors of Scotland, where my search for elusive frogs and newts in garden ponds to misty peat bogs ignited a passion that fueled a quest to unravel the mystery of vanishing frogs from Central and North America to Australia; their disappearance sometimes so rapid that not even a corpse was left to mark their existence. In the second part of the story we embark on a journey with scientists around the world in search of frogs and other amphibians not seen in decades, before taking a step back to consider, in the final part, what the successes and the failures mean in the grander scheme of things. It is a story of rediscovery, reinvention and hope; a story about the fine line between life and death, and what it is telling us about the sixth mass extinction on earth.

CHAPTER 1

SPAWNING A PASSION

I have always liked frogs. I like the looks of frogs, and their outlook, especially the way they get together in wet places on warm nights and sing about sex.

ARCHIE F. CARR, THE WINDWARD ROAD

Edinburgh, April 1981

It is a crisp April afternoon in Edinburgh, filled with the comforting hum of distant lawnmowers and the sweet scent of freshly cut grass. I am six years old, buzzing with the thrill of exploration as I track glistening snail trails on the grey stone wall that lines my grandparents garden, when an unusual sound breaks the silence. Raaack raaaack raaaack, waaaaaarp . I wiggle my fingers into the cracks between sun-warmed stones and scale the wall that separates me from the sound. As I flop belly-first onto the top of the wall and peer into the neighbours garden, I am treated to a sight that I will not forget.

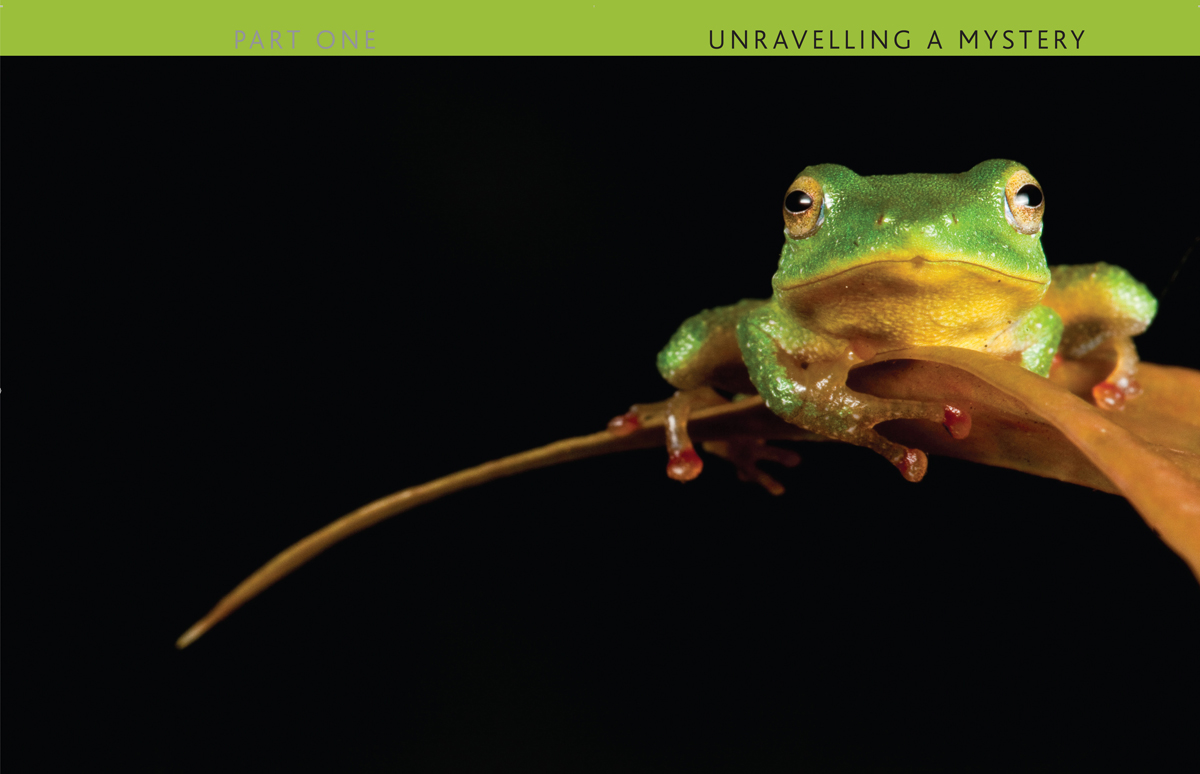

A small pond fringed by untamed grass thrums with life. The water bristles as frogs plop and wrestle in the shallows. I slide backwards down the wall into the neighbours garden and, as my feet make contact with the ground, a frog springs from under me, skidding to a halt next to the pond. I steal closer before pouncing to clasp the frogs bulbous waist. Her soft belly folds around my slender fingers like Play-Doh; she is loaded with eggs. She is resigned to this intrusion without struggle, and fixes me with what I take to be a look of mutual curiosity.

Common Frog, Rana temporaria, Scotland.

And this is when it happens. Her large inquisitive eyes and half-smiling mouth speak to me. Her primal form exudes the untold wisdom of a creature that has roamed the earth long before humans were even a distant promise; a creature that has rubbed ankles with the dinosaurs. The animal is as intriguing in life as in mythology; a mystique that is amplified by evanescence. After their explosive performance in the pond the frogs disappear as quickly as they arrived, spending the remainder of the year in the landscape of my imagination. Upon their disappearance they leave behind, bubbling from the surface of the pond, tickets to one of the most miraculous shows on earth. To snag my ringside seat, I return to the pond the following Sunday to plunge a hand into one of the cold, quivering masses. It feels like soft jelly marbles running through my fingers as I detach a small clump of spawn and plop it into a jam jar filled with water. Back home I transfer it to an aquarium, carefully lined with pebbles and decorated with sprigs of pondweed, to witness the magical transformation.