One day I went out with some merchants to hunt in the immediate vicinity of the city.

Our sport was very poor; but I had an opportunity of seeing the ruins of one of the ancient Indian villages, with its mound like a natural hill in the center.

The remains of houses, enclosures, irrigating streams, and burial mounds, scattered over this plain, cannot fail to give one a high idea of the condition and number of the ancient population. When their earthenware, woolen clothes, utensils of elegant forms cut out of the hardest rocks, tools of copper, ornaments of precious stones, palaces, and hydraulic works are considered,

it is impossible not to respect the considerable advance made by them in the arts of civilization.

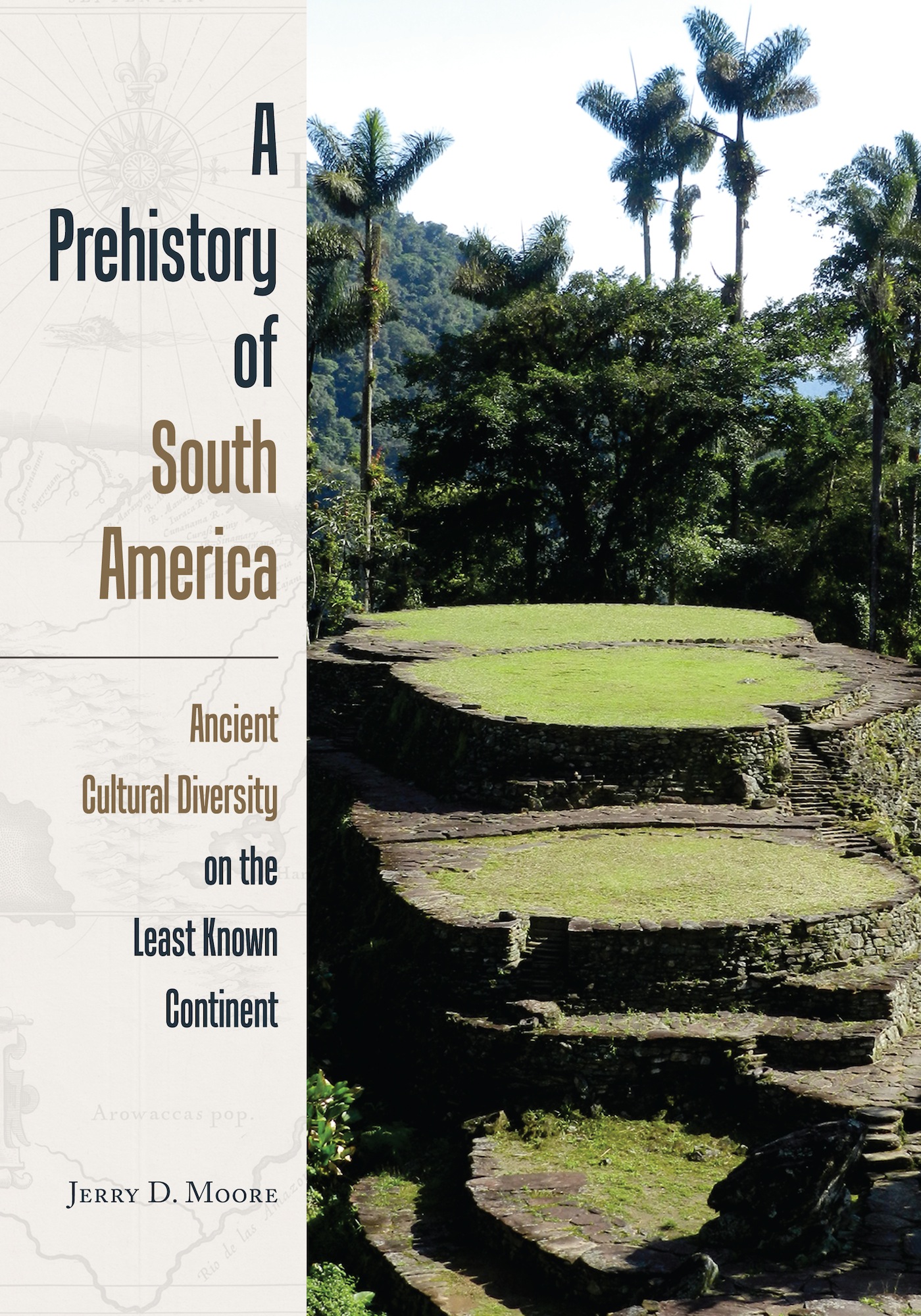

A Prehistory of South America

Ancient Cultural Diversity on the Least Known Continent

Jerry D. Moore

University Press of Colorado

Boulder

For Carol J. Mackey and A.M. Ulana Klymyshyn

2014 by University Press of Colorado

Published by University Press of Colorado

5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C

Boulder, Colorado 80303

All rights reserved

Printed in Canada

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University.

This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

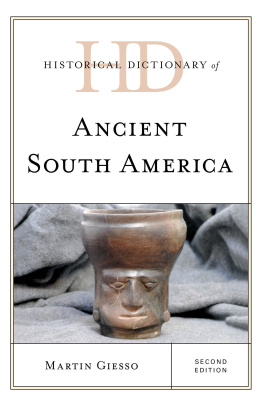

Moore, Jerry D. A prehistory of South America : ancient cultural diversity on the least known continent / Jerry D. Moore. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-60732-332-7 (pbk. : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-1-60732-333-4 (ebook) 1. Indians of South AmericaAntiquities. 2. Paleo-IndiansSouth America. 3. Prehistoric peoplesSouth America. 4. Cultural pluralismSouth AmericaHistoryTo 1500. 5. Social archaeologySouth America. 6. South AmericaAntiquities. I. Title. F2229.M66 2014 980.01dc232014004806 Design by Daniel Pratt

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cover illustrations: Ciudad Perdida ceremonial axis, photograph by Jerry Moore (front); Willem Janszoon Blaeus 1635 map of the northwestern parts of South America, Lake Parima, and the route to El Dorado, public domain image courtesy of Geographicus Rare Antique Maps (background).

Archaeology in South America

A Brief Historical Overview

Let us come to the rational animals.

We found the entire land inhabited by people completely naked, men as well as women, without at all covering their shame. They are sturdy and well-proportioned in body, white in complexion, with long black hair and little or no beard. I strove hard to understand their life and customs, since I ate and slept with them for twenty-seven days; and what I learned of them is the following.

1502 letter from Amerigo Vespucci to his patron, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de Medici

Current archaeological knowledge builds on several centuries of interest in the antiquities and monuments of South America, although interest motivated by very different goals and practices. The first European descriptions of South American objects and sites were the by-products of conquest. Soldiers accompanying Francisco Pizarros expeditions in 153233such as Miguel de Estete and Pedro Pizarrodescribed the towns and monuments of native kingdoms, in the process providing valuable accounts of the Inca Empire. The soldier-chronicler Pedro de Cieza, who arrived in America as a fourteen-year-old in the 1530s to seek the riches of the New World, was also an astute observer with an eye for detail, describing ancient road networks, fortresses, temples, and other native constructions between Colombia and Cusco. Catholic priests described the ritual artifacts and sites used by native peoples, usually to replace native religion with Christianity. Father Jos de Arriagas 1621 The Extirpation of Idolatry in Peru was a descriptive guidebook to Andean religion, listing sacred places and artifacts so local Catholic priests could recognize and eliminate pagan beliefs. A more sympathetic and extraordinarily valuable document was prepared in the early 1600s by the bilingual mestizo author Guaman Poma de Ayala, who wrote a 1,400-page document, The First New Chronicle and Good Government, in which he argued that the Spanish conquest was unjust and the colonial system cruel, supplementing his argument with hundreds of drawings illustrating Andean culture and Spanish inequities. In the early seventeenth century, Father Bernabe Cobo wrote detailed accounts of Inca religion and culture. Although none of these documents were focused on the scholarly study of South American cultures, they are valuable sources of information, particularly about the Incas.

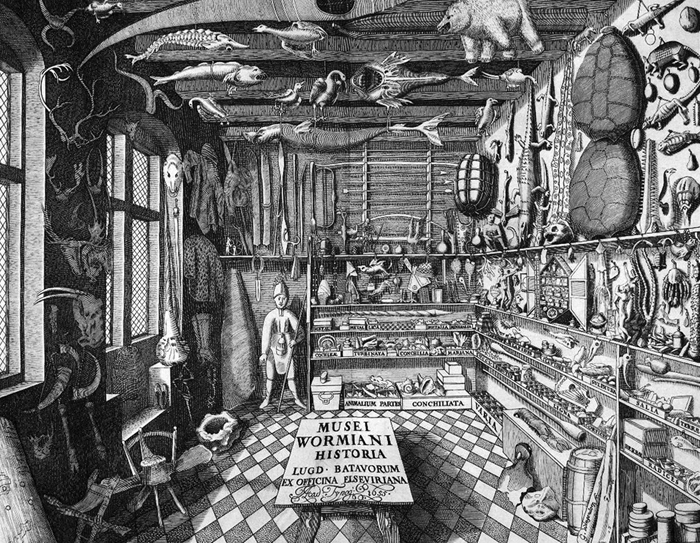

Figure 1.1 A 1558 map of South America

A theme that emerges from these accounts, particularly in the Andean region, was the recognition thatdespite the achievements of the Inca Empiresome sites were the creations of earlier peoples, often vaguely described as the huaris (Quechua for ancestors or old ones.) Some of these pre-Inca cultures had been recently assimilated by the Incas just before the Spanish conquest, and their names were still remembered. One of these cultures was the Chim of the North Coast, who had been conquered by the Inca only a few decades before the Spaniards had conquered the Inca. Earlier cultures, however, were anonymous and unrecorded by Spanish chroniclers.

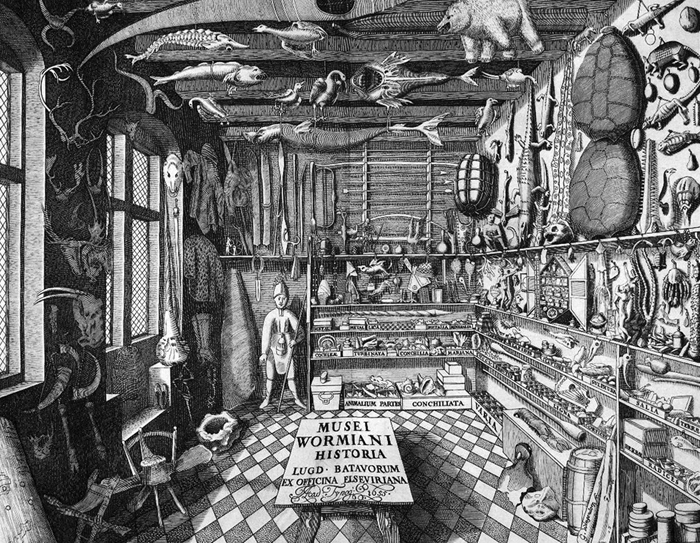

Exotic Curiosities and Cabinets of Wonder

).

Figure 1.2 A 1655 cabinet of wonderfrontispiece from Museum Wormianum by Danish naturalist Ole Worm (15881655)

In 1752 the Spanish natural historian and diplomat Antonio de Ulloa proposed establishing an Estudio y Gabinete de Historia Natural in Madrid that would house objects Ulloa and others had collected on their voyages. Not until 1771 did the Spanish king, Carlos III, establish the Real Gabinete de Historia Natural, issuing a decree to his global empire to collect and send objects of interest to Madrid. The collections included natural specimens, paintings, and other artworks, as well as antiquities. Opened in 1776 and looted by Napoleons forces in 1813, the Real Gabinete de Historia Natural was transformed into the Real Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Madrid, the institutional ancestor of the current Museo de America.

The Spanish clergyman Baltazar Jaime Martinez de Companion, who served as bishop of Trujillo from 1778 to 1790 and whose diocese included the coast, highlands, and jungle regions of north-central Peru, prepared a remarkable nine-volume document known as Trujillo del Peru. Lavishly illustrated with watercolors portraying colonial society, documented with detailed maps and plans, and even containing musical scores of folksongs, the ninth volume of