May 2015

Leaving Cusco, the road to the Fiesta of the Lord of the Snows actually continues across South America to So Paulo, Brazil, but after five hours we got off the bus at Mahuayani. Usually, Mahuayani is a small settlement that straggles along the two-lane blacktop, but in late May and early June impromptu food stalls and shops sprout up at the trailhead leading to the chapel of the Lord of the Snows, or El Seor de Qoyllur Riti. The Fiesta de Qoyllur Riti has deep and tangled origins. The fiesta may have pre-Columbian roots and is certainly embedded in indigenous Andean belief and practice. The fiesta is a movable feast, calibrated by the reappearance of the Pleiades in the southern Andean night. The Pleiades mark the important beginning of an agricultural cycle, and the brightness of the constellation in mid-June is used to predict the abundance of future rains. Some anthropologists have suggested that Qoyllur Riti began as pilgrims from the eastern tropical lowlands climbed west into the high Andes. The ritual guardians who police the fiesta are the ukukus, young men in shaggy, black wool chaps who represent the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) that live in the cloud forests in the eastern montaa and allegedly sneak into the Andes to have sex with Quechua women. Today, Qoyllur Riti attracts campesinos from Quechua and Aymara villages but also large numbers of mestizos from Cusco and other Peruvian cities and towns, some New Age adherents attracted by the spectacle and sacredness, other foreign tourists, andof courseme.

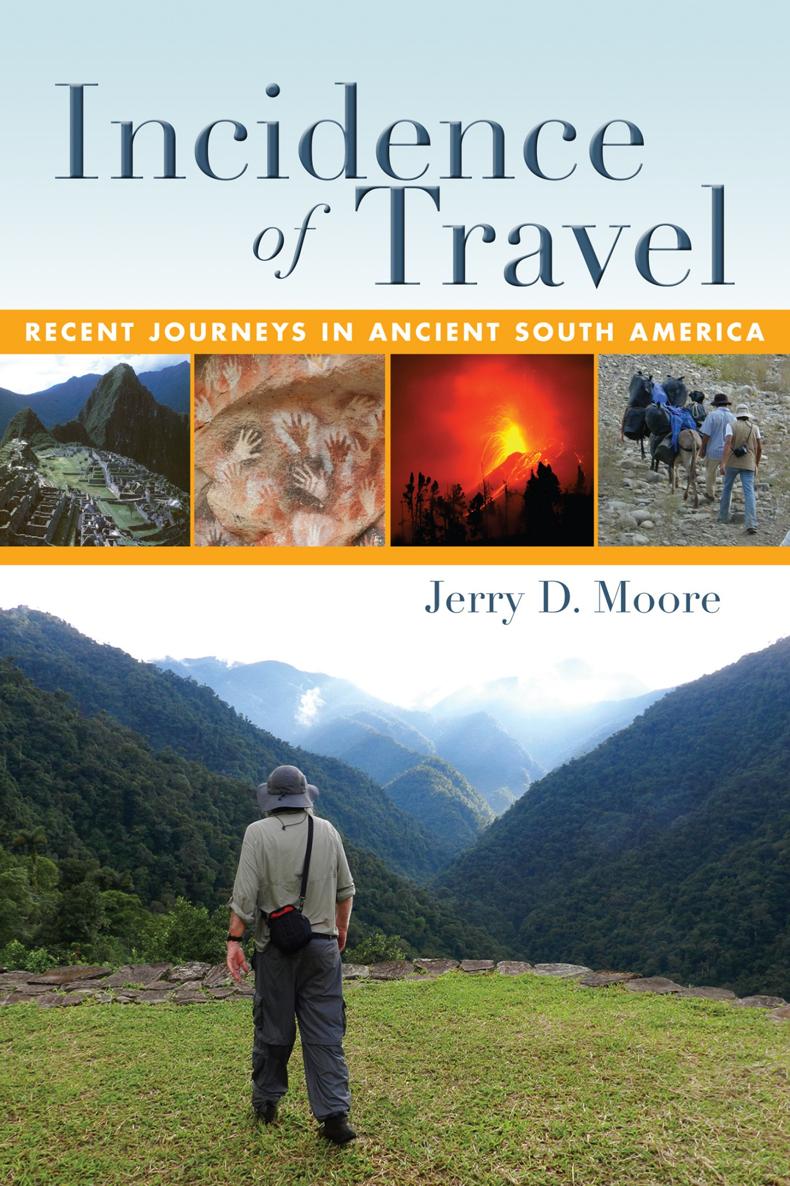

I am here because I am an archaeologist. I am interested in the ways humans mark their presence on the landscape, a broad field of inquiry into cultural landscapes and the archaeology of place, exploring the ways in which people impart meaningboth symbolically and through actionto their cultural and physical surroundings at multiple scales and... the material forms these meaning may take. I conduct archaeological fieldwork in South America, principally on the northern coast of Peru, but I also travel across South America to visit other sites, museums, places, and ceremonies to learn about the ways humans inscribe their presence on the earth. And that is why I am here.

I was guided to the fiesta by Angel Callaaupa Alvarez, an extremely accomplished man from Chinchero, Peru: climber, expedition guide, an activist working on problems of food security in high Andean villages, and an artist with several book credits. (Angels early artwork was used in the seldom-seen 1971 film The Last Movie, directed by Dennis Hopper.) We were joined by Arnold, a quiet young man in his mid-twenties who studied archaeology and museum studies at the Universidad San Abad del Cusco. In Mahuayani, Angel led us to a tarp-covered kitchen run by friends from Chinchero, where we sat at rough plank tables and ate bowls of mutton and noodle soup. Great commotions swirled around us. This was the beginning of the four-day festival, and while some of the kitchens and stalls were already in business, other folks were still stringing blue plastic tarps, arranging cooking hearths, and unloading goods to sell to the pilgrims. The pilgrims hike 9 km to over 4,300 m above sea level to the chapel of Qoyllur Riti that sits below three glaciers at the base of Mount Qulqipunku, the Silver Gate, an apu, or mountain deity, who watches over the health and well-being of people.

Angel arranged for a packhorse to carry our gear and another horse for him to ride, and he went on to set up camp. Arnold and I began to hike, lightly burdened with water, camera, and rain gear. The sun was out, and it was about 50F as we hiked. The first pitch of the trail was extremely steep. We began at 3,880 m and climbed higher. I was constantly out of breath. The trail leveled to a more gentle but constant grade, following a stream that flowed from distant glaciers. The hillsides flanking the trail were very steep. White llamas grazed on the slopes.

We passed clusters of vendors shops at various points along the trail, generally at broad, flat spots or at specific kilometer posts. On the lower reaches of the trail the vendors sold food and drink, but as we climbed, more and more of the shops offered ritual items. Candles and images of Christ were for sale, but most of the items were miniature objects of desire. A principal reason for journeying to Qoyllur Riti is to demonstrate ones faith to the Lord of the Snow Star and to ask for help in attaining ones dreams. There were small automobiles and pickup trucks for those who desired transportation and miniature bundles of money (both Peruvian soles and US dollars) for those who wished for wealth. A variety of types of miniature real estate was offeredhouses, apartment buildings, and entire hardware storesnone larger than a pack of cigarettes. If you wanted to be well-educated or improve your professional standing, you could buy miniature diplomas and certificates that would ensure you would become

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.

The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses.