For Alison. With fond memories of the seaside summers of our childhood... and thank you for forgiving me over the beach-ball incident.

Bloomsbury Natural History

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2015

Marianne Taylor, 2015

Photos Marianne Taylor 2015 except as noted

Marianne Taylor has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organisation acting on or refraining from action as aresult of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: PB: 978-1-4081-8178-2

ePDF: 978-1-4081-8640-4

ePub: 978-1-4081-8641-1

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

Introduction

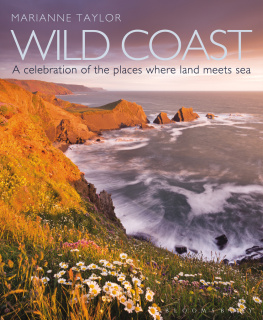

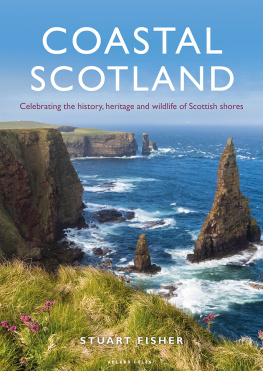

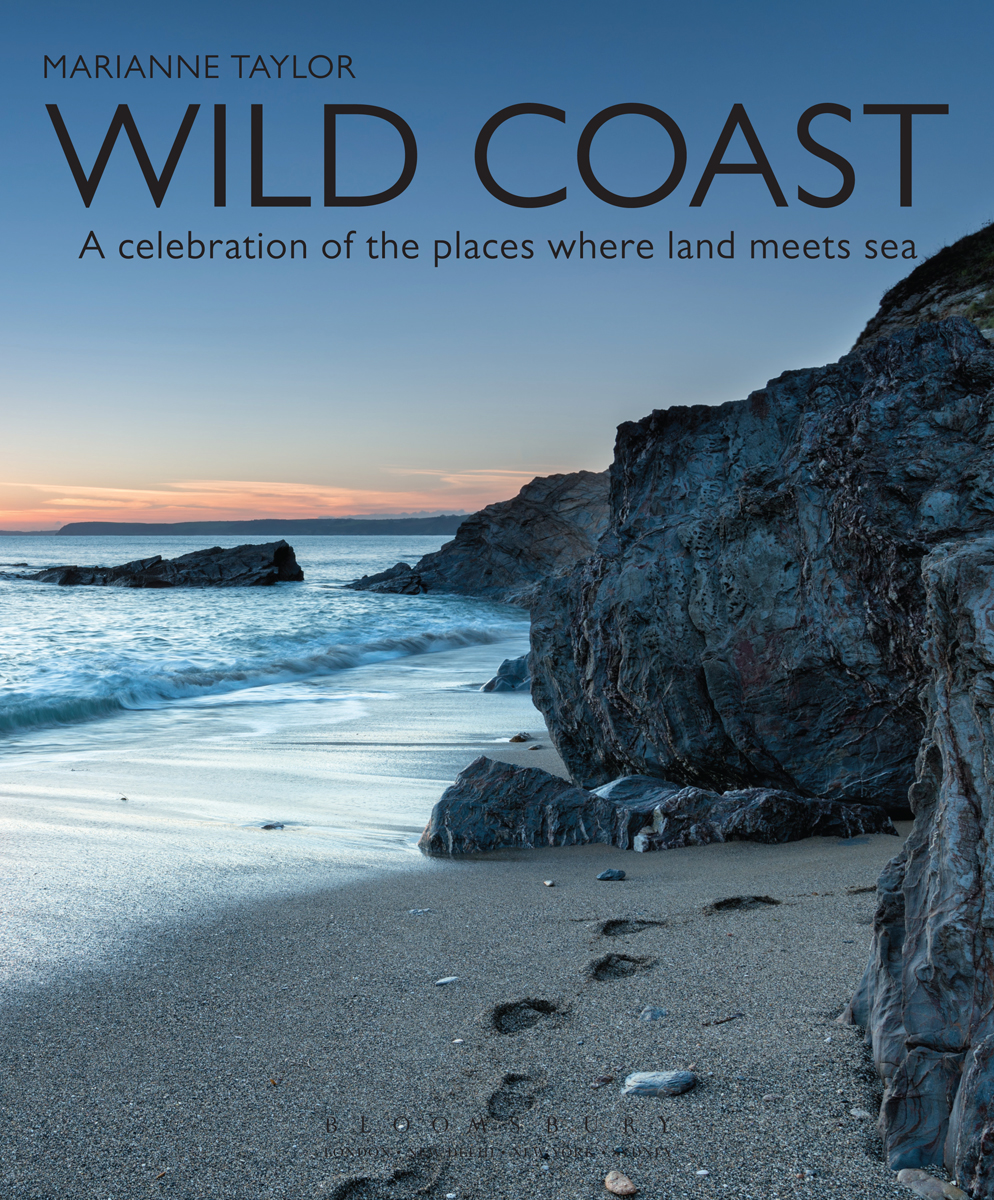

Everyone who enjoys country walks and wildlife-watching will have noticed the special magic of the edge where one kind of habitat meets another. Meadows adjoining woodland, the uplands where forest gives way to open moor or heath, the reedy margin of a lake all are places where wildlife seems particularly rich and abundant. The animals and plants typical of each habitat type are joined by others, adapted to the particular features of the edge in question, or adapted to move easily between the two contrasting habitat types. This effect is no more striking than along our coastline the point where land meets sea.

Nowhere in the British Isles is more than 113 kilometres from the sea, and the ratio of coastline to land area is very high compared to similar-sized island groups. Our coastlines course is, in many regions, akin to a highly challenging rally course, with sweeping chicanes one moment and tight hairpins the next, and with more than 1,000 smaller islands on top of the main land masses of Great Britain and Ireland, the total length of coastline is well over 20,000 kilometres although differing methods of measurement makes it extremely difficult to assign a definitive value. Along this course, our coastal terrain changes from shingle to sand to cliff to mudflat to boulder-beach, each hosting its own distinct wildlife community. In some areas, the coastal flavour of the habitat reaches back inland many kilometres, along the banks of tidal rivers for example. With seaside towns, once you are off the beach and beyond the esplanade it can seem no different, from a wildlife point of view, to any inland town but there are differences, if you know where to look for them.

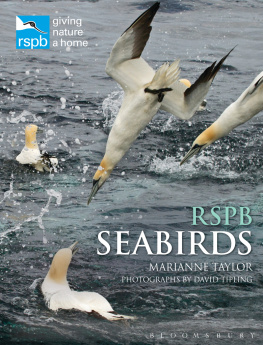

The wilder parts of the British coastline harbour some very special animals and plants, and their populations here are of global significance. For example, of the 25 species of seabirds that breed on our cliffs and beaches, 21 are here in internationally important numbers. While no seabirds breed only in the British Isles, we do have more than 93 per cent of the worlds breeding Manx Shearwaters, and more than 50 per cent of the worlds Gannets and Great Skuas. Some less noticeable coastal species are indeed unique or endemic to the British Isles, such as Eudarcia richardsoni, an exquisite little piebald moth found only on the Dorset coast, the beautiful Scottish primrose that flowers only on the north coast of Scotland, and the miniscule Ivells Sea Anenome, known only from Widewater Lagoon in Sussex.

The coast also offers temporary lodgings for some of the worlds great animal travellers, with hundreds of thousands of migrating waders stopping off at our estuaries on their migrations, and more than a quarter of the worlds 96 species of whales, dolphins and porpoises regularly visiting our inshore waters. Our islands lie across a point where cool polar waters collide with warm water brought our way via a current known as the North Atlantic drift, and they are also the first landfall for flying animals that are pushed across the Atlantic by the prevailing westerly winds. It is no surprise that a huge diversity of species has been recorded along British coasts.

The human population of Britain has an innate attachment to the coastline, with research indicating that most of us would much rather spend a day at the seaside than walking in the countryside, and in the UK five per cent of us live by the sea thats three million people, many of them in coastal cities like Brighton, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Cardiff, Swansea, Liverpool, Newcastle, Belfast and Edinburgh. For the 57 million UK citizens who live inland, holidays by the seaside are enduringly popular, with dozens of sleepy coastal towns coming to life in summer as holidaymakers swarm in. Tourists may temporarily double or triple a seaside towns population, and their needs provide for hundreds or thousands of seasonal jobs. Coastal development to support the tourist trade has inevitably resulted in the destruction or deterioration of large tracts of formerly wildlife-rich habitat, although this pattern of loss shows huge variation from one end of Britain to the other.

Not all seaside tourism is bad news for wildlife. From many seaside towns you can book a boat tour in search of seabirds, cetaceans and other marine life such trips are becoming increasingly popular in some areas, and of course they depend on the protection of the wildlife itself as well as coastal and marine habitats. Some coastal holiday-makers come in search of nothing but wildlife, and in many parts of the British Isles it is easy to fill a week based at a seaside town with visits to a succession of nearby coastal nature reserves.

Observing the daily life of Puffins, such as these on Skomer island, Pembrokeshire, is one of the great joys of coastal wildlife-watching.

Migrating Whimbrels and other Arctic-breeding waders will stop off at suitable coastlines anywhere in Britain.

The British Isles is a world leader for marine mammal-watching, with great opportunities to see cetaceans such as Common Dolphins.

VISITING THE COAST

Walking and looking for wildlife in coastal habitats is hugely rewarding and enjoyable, but in a few areas there are certain hazards to keep in mind. A modicum of planning and common sense is needed to ensure nothing happens to spoil your day.