Pagebreaks of the print version

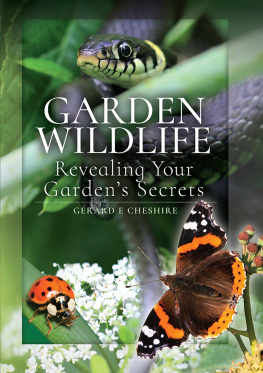

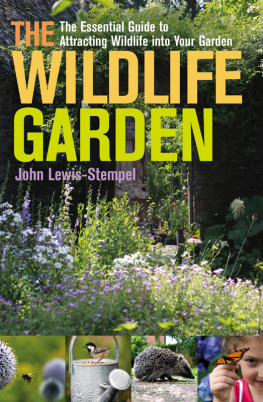

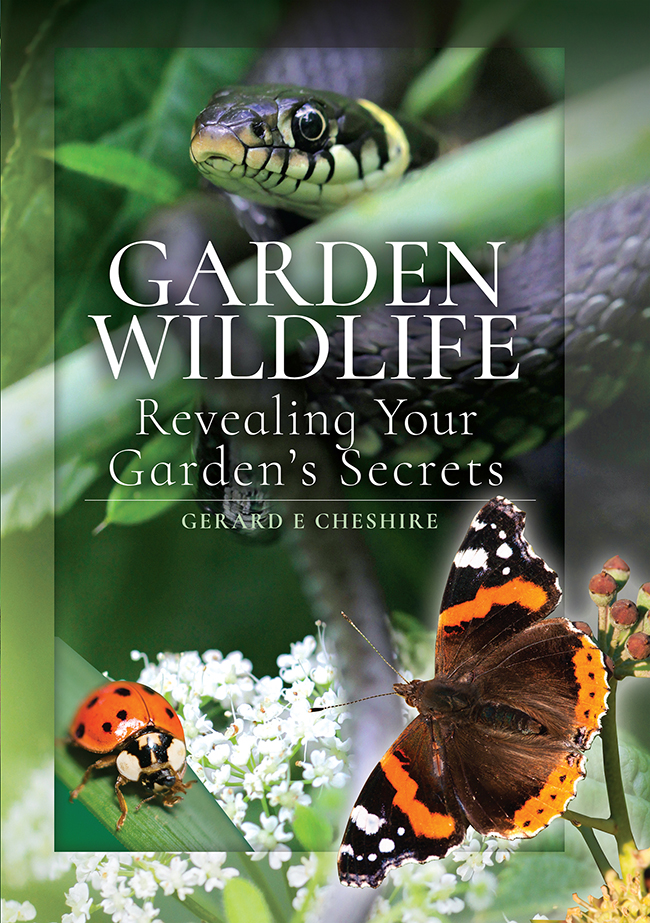

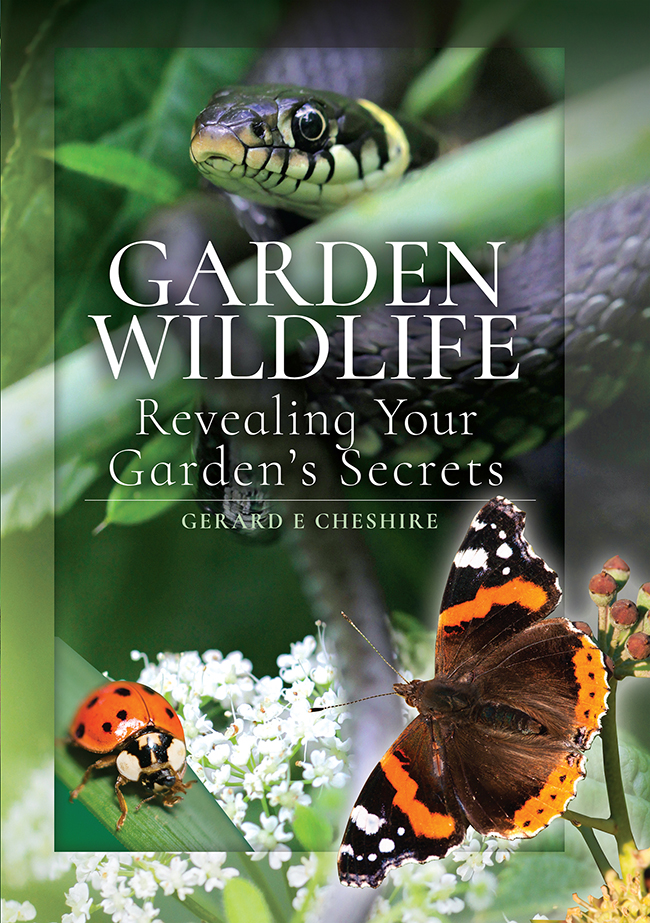

GARDEN WILDLIFE

Revealing Your Gardens Secrets

GARDEN WILDLIFE

Revealing Your Gardens Secrets

GERARD E CHESHIRE

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

PEN & SWORD WHITE OWL

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Gerard E Cheshire

Hardback ISBN 9781526729699

Paperback ISBN 9781526751522

eISBN 9781526729705

Mobi ISBN 9781526729712

The right of Gerard E Cheshire to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Aviation, Atlas, Family History, Fiction, Maritime, Military, Discovery, Politics, History, Archaeology, Select, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Military Classics, Wharncliffe Transport, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing. For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

INTRODUCTION

T he aim of this book is to encourage the reader to think about their garden in a new way. We have long been used to the idea that a garden should be a manicured, kempt and ordered space, almost as if it were an external room. As a result, many gardens have become unnatural and sterile even though they may have lawns, shrubs and flowerbeds in abundance. This is because lawns and flowerbeds are frequently free of the self-seeded plants we often call weeds. In addition, the majority of garden plants are non-indigenous species and cultivars that offer nothing to our indigenous wildlife. Furthermore, gardens are kept so tidy that there are few compost heaps, log piles and overgrown corners in which animals can make their homes and forage for food.

Therefore, the new way of looking at our gardens is simply to reject this nonsense and accept a return to the old way of looking at our gardens, as natural and wild spaces, rather than unnatural and tame spaces. To let them get a bit untidy and to allow nature to reclaim them; to stop using weed killers and bug sprays and to allow our indigenous plants and creatures to reinvade our green spaces; to begin thinking of our gardens as a network of habitats that allow and encourage our wildlife to continue living alongside us, even in the housing estates that steadily spread as the mark of modern suburbia.

As this book is about wildlife found in gardens, then it focuses on those species that are most likely to be seen in typical gardens, rather than providing comprehensive coverage of all species, as many species are seldom seen in gardens, unless those gardens happen to be in unusual localities. The idea of a garden safari is to consider a typical garden in terms of the different habitats it offers from one corner to another, in much the same way that a real safari moves from habitat to habitat.

So, we have lawns that equate to meadow and grassland, we have ponds that equate to wetland and marshland, we have paths, patios and drives that equate to exposed bedrock, we have the hedgerows that equate to woodland, we have flower beds and vegetable patches that equate to forest clearings, we have walls that equate to cliff faces, we have roofs that equate to escarpments, we have rockeries that equate to plateaux, we have the forgotten corners, which equate to undergrowth and thicket, and we have sheds, garages and summerhouses that equate to caves, voids and hollows. Thus, within a typical garden there is usually quite a range of habitats from the point of view of wild plants and animals, even if we dont readily see it ourselves.

In fact, this inadvertent division of our gardens into many small habitats can mean that they offer sanctuary to a greater variety of species than might have been present in the landscape before the land was developed. When we put them all together, they offer a vast patchwork and network of small habitats that enable whole populations of many species to survive and flourish alongside us. All we need to do is be a bit more carefree about what the neighbours think, so that those habitats can come into their own.

Perhaps the best way to appreciate the way our wildlife views our gardens is to think about scale. Most plants and animals are a good deal smaller than we are, so they dont need that much space in order to make garden habitats their homes. Those that do require more space simply treat our gardens as a collective habitat, so they ignore our concept of boundaries and move about as they choose, on the ground, through the foliage or in the air. The notion of delineated land ownership is largely a peculiarity of humanity, although some species are territorial in order to maintain sufficient resources for their survival and reproduction. Many garden animals are diurnal (active by day), while others are crepuscular or nocturnal (active at twilight or by night). So, there are likely to be many more species living in our gardens than we immediately realize. In addition, the time of year can affect our observation of different species. Many sedentary species hibernate during the colder months, while others remain active. There are also migratory species, some of which depart for the colder months, while others arrive for the colder months. The life cycles of many species also dictate the way we see them during the seasons, as most breed annually, so the young and adult stages will appear at different times of the year. Of course, many animals hide from predators or secrete themselves in dark and damp places to avoid drying out. This often means that they live under objects close to the ground, or they live below the surface in cavities, holes and burrows. Still others rely on camouflage, meaning they are overlooked even when they are out in the open. Furthermore, many aquatic species spend much of their lives hidden in the mud and weeds in our ponds.Taking all of these factors into account, it becomes apparent that we are only likely to see a few of the species in our gardens at any one time of the 24 hour day or on any one day of the year. The total species count is therefore likely to be far higher than we realize. They only practicable way to find out how many species visit our gardens is to record them over a number of years and to regularly spend some time actively searching and observing.

We can also make additions to our gardens to encourage more species in, by providing food sources and places to breed, so that visiting individuals are more inclined to stay, rather than move on. One problem with modern gardens is that large trees are often scarce or absent, and those that do exist are seldom allowed to develop cavities and rotten limbs. This means that arboreal species have very few places to set up natural homes in suburban and urban environments. This is where it becomes important to introduce nesting boxes, roosting boxes, decaying logs, and so on, so that these species are supplied artificially with what they need.