Contents

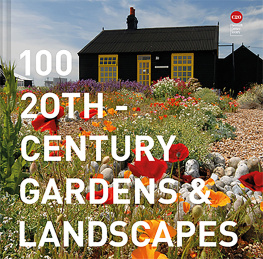

Guide

Hemel Water Gardens, Hertfordshire

CONTENTS

Foreword

Catherine Croft

Introduction

Susannah Charlton

The Private Garden in the 20th Century

Barbara Simms

Geoffrey Jellicoe and the Landscape Profession

Alan Powers

Landscaping to the Horizon

Elain Harwood

Recognising the Value of Modern Urban Landscape

Johanna Gibbons

FOREWORD

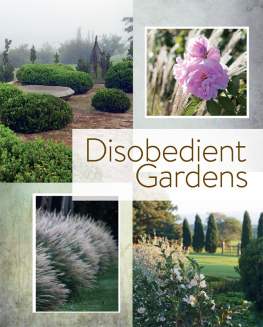

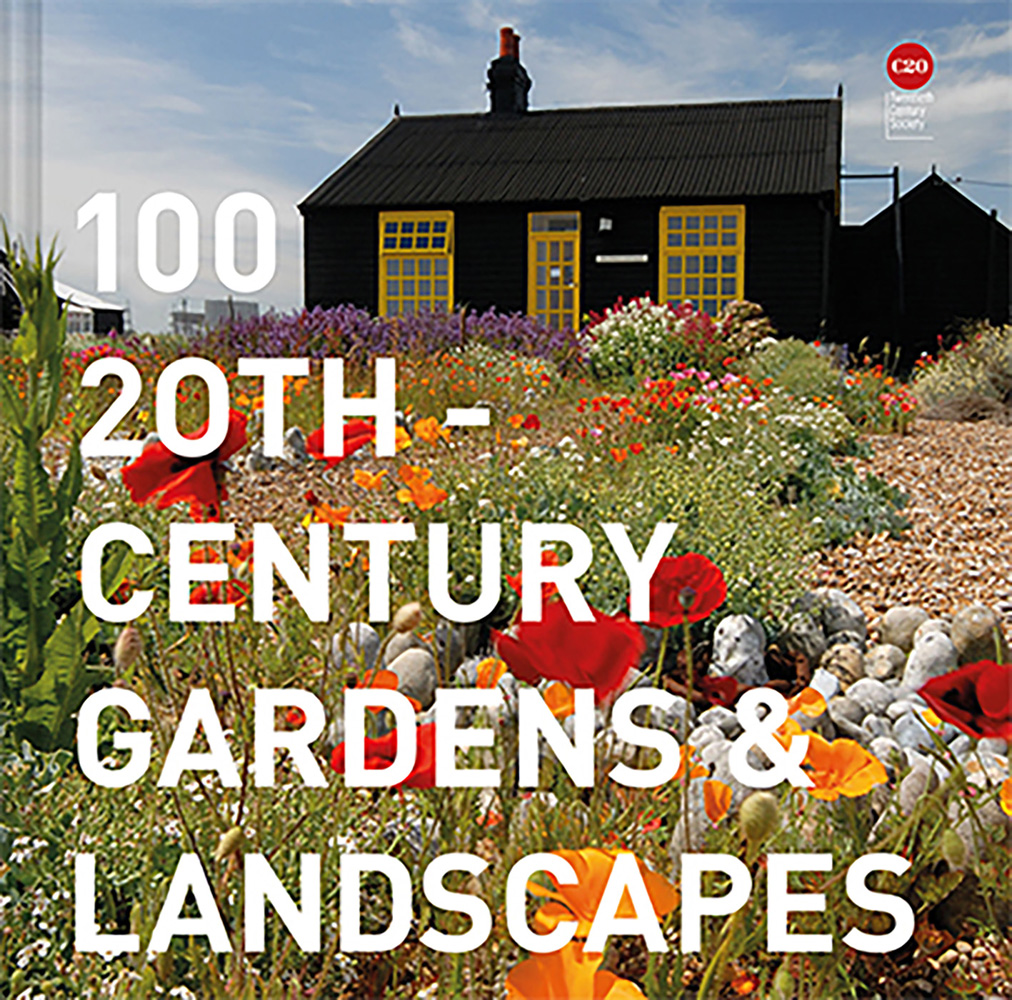

100 20th-Century Gardens & Landscapes gives an overview of the radical changes that have taken place in the landscapes that surround us during the past century, both in how they were created and how we use them. It is both a history and a celebration. The Twentieth Century Society is primarily focused on buildings, but we work to protect landscapes too, especially where they were planned together with buildings as a complete ensemble. We are a conservation organisation, and landscapes offer different challenges to buildings. While a building is usually deemed complete when the builders leave site, gardens are planned to grow and develop; the intended final effect may only be achieved many years later, when plants and trees have had time to mature. Some elements can run wild, others decay. What does this mean for restoration objectives? To what state should a restoration aim to return a landscape to? And to what extent do we see gradual changes as part of a natural process akin to the patination of building fabric?

Landscapes are even more vulnerable to redevelopment pressures than buildings, be it complete redevelopment, or infilling spaces between buildings for financial gain or to accommodate a growing organisation. Neglect or lack of maintenance can have a major impact far more quickly than a similar disregard for a relatively robust building. Planting has also to evolve, to cope with changing uses and the changing climate.

Statutory consultees, like the Twentieth Century Society and the Gardens Trust, can often only intervene to save a landscape at the eleventh hour when it is under imminent threat. Many excellent designed landscapes may not meet the demanding criteria for registration by Historic England, and need protection by other means. Measures such as covenants to protect the landscape, as used at the Span estates or Hampstead Garden Suburb, can better help to maintain the planting and character of shared green space and streetscapes. Perhaps even more important is that people understand and appreciate the everyday landscapes around them. We hope this book will spur you to visit this very diverse group of places, some of which may not initially appear to be the work of designers at all.

The Twentieth Century Society is a tiny organisation facing growing demand for the conservation advice, research and campaigning that we undertake, as more of the heritage we champion comes under threat. Please join our many members, who enable us to protect outstanding 20th-century buildings and landscapes.

Catherine Croft

www.c20society.org.uk

Span Estate at Templemere, Surrey

INTRODUCTION

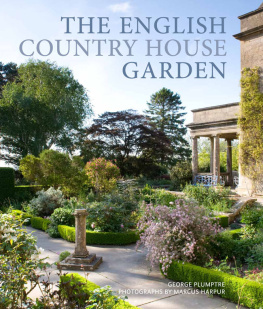

It was once obvious what constituted a garden or a landscape. There were the grandiose private gardens of the wealthy and/or privileged, and for the rest of us there were public parks and squares laid out by municipal authorities. Or so it seemed until the20th century.

Grand gardens continued to be formed, but many more people now had their own plot, however small, to create a significant outdoor space or garden room, as Thomas Church and John Brookes described urban gardens. Many more varied public spaces began to be created, ranging from the poignant war memorial or crematorium garden, to those that celebrated a festival, the Millennium, or more enigmatically the worlds hopes for peace. Landscaping became a wider part of the public realm, especially after World War II. New towns, housing estates, universities, reservoirs and motorways even new forests were planned to look good as well as to serve their users, so that the hand of mankind has a hold over the landscape everywhere we go in town and country today. This diversity and the importance of landscape reflects the egalitarianism and optimism that were so important to all that was good about the 20th century.

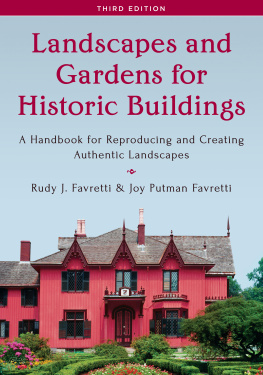

The most distinguished and significant of these gardens and landscapes deserve to be understood, appreciated and protected as an important record of British life, just as much as the gardens and landscapes of earlier centuries. In many cases, they form part of a complete ensemble with significant post-1914 buildings, either because they were designed at the same time, in collaboration with the architect, or because they constitute an important context for that architecture.

The Twentieth Century Society campaigns to protect landscapes as well as buildings. This is easy to explain where buildings and their landscape form an ensemble. It is more challenging when the landscape is a subtle streetscape or park that we take for granted with benign indifference, yet is an important part of the designed landscape. Public landscapes do not have the protection of a wealthy owner with the long-term vision and resources to help them survive for the future. Townscapes are particularly subject to the relentless pressures of austerity Britain, from council maintenance cuts to commercial redevelopment or privatisation, which reduce the sense of communal ownership of landscapes designed for public good. Even when their significance is recognised, well-meaning incremental changes intrusive safety rails, excessive signage, inappropriate sculpture or new planting can erode the quality of the very design they were supposed to protect or enhance.

As land values rise, the speed of demolition increases, especially in the commercial sector when changing ownership, obsolete facilities or the need to expand exert powerful financial pressures. The RMC head office in Surrey with its exceptionally accomplished and richly detailed landscape design combining courtyards and rooftop gardens was threatened with demolition just 25 years after its completion in 1990. Thankfully this has been saved, and in 2019 the Society was able to get not just one, but three listings for the Pearl Assurance headquarters outside Peterborough: the building at Grade II, the war memorial at Grade II*, and the 25 acres (10ha) of landscaped grounds registered at Grade II. The grounds were designed by Professor Arnold Weddle, whose highly creative re-working of a familiar formal language complements the post-modern design of the Pearl Centre. However, the listed Birds Eye offices in Walton-on-Thames, with landscaping by Phillip Hicks, was demolished in 2019. Despite our sustained objections, the beautifully executed essay in modernist landscape that was designed by architects Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners with planting by Sylvia Crowe for the Commonwealth Institute in London was delisted and demolished when the building was redeveloped in 201516 for the Design Museum. This shows how vulnerable even a registered landscape can be if the local authority and Historic England do not ensure that it has the robust protection it deserves.