Yew pillars regenerating after pruning at Hidcote.

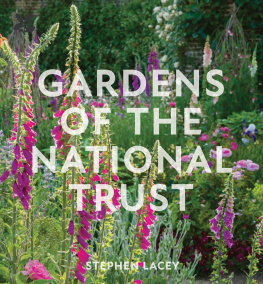

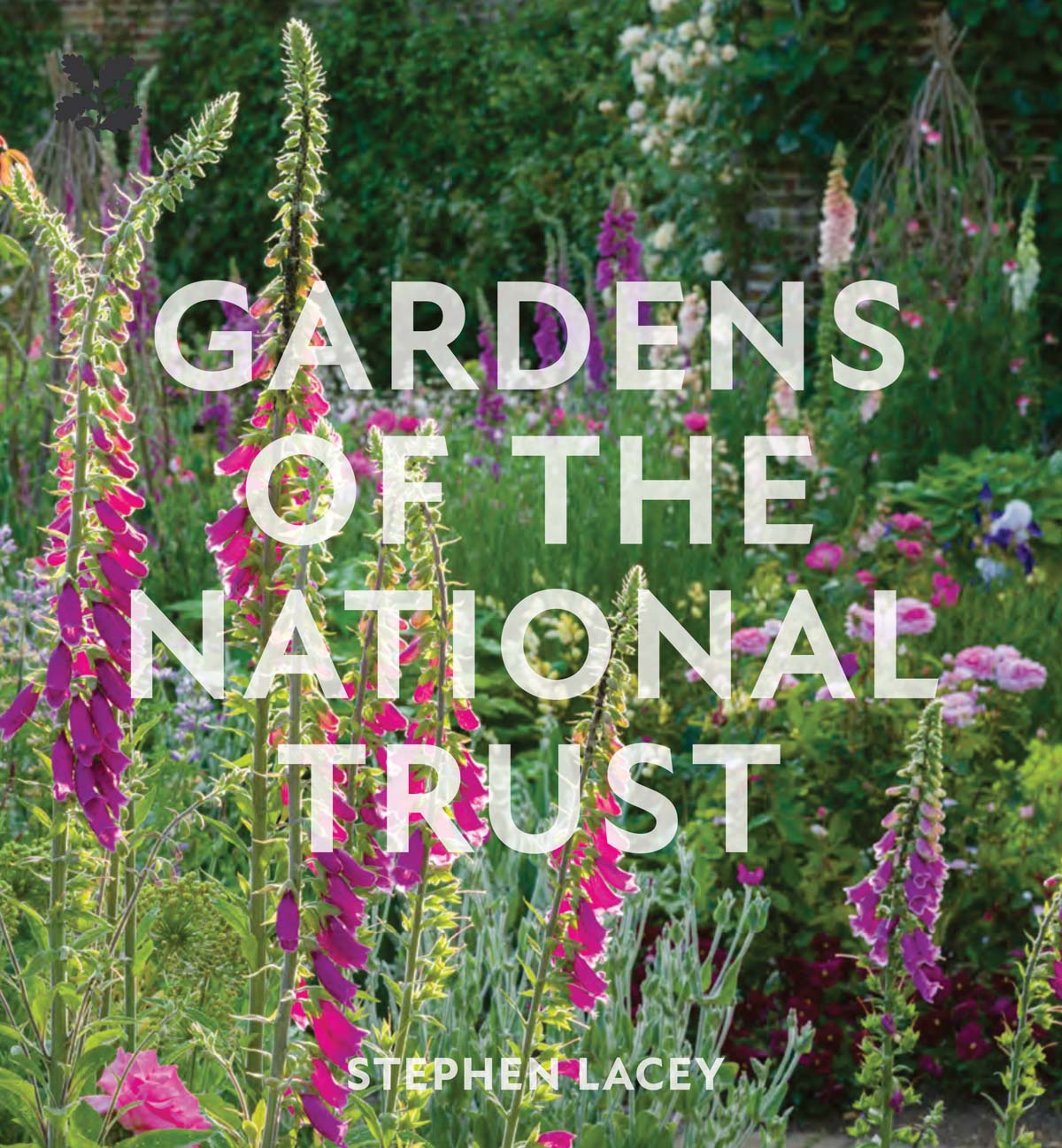

Front cover: Sissinghurst Castle Garden, Kent (National Trust Images/Andrew Butler).

Back cover, top: Ham House, London (National Trust Images/Chris Davies); back cover, bottom: Penrhyn Castle and Garden, Gwynedd, North Wales (National Trust Images/John Miller).

Stephen Lacey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information and storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Colour and fantasy in the Formal Garden at Mount Stewart

National Trust Images/Andrew Butler

Contents

Three gardens make their debut in this revised edition of Gardens of the National Trust: Wentworth Castle Gardens in Yorkshire; Allan Bank, William Wordsworths home overlooking Grasmere; and High Close in the Lake Districts fells. Several gardens have colourfully expanded the acreage open to visitors, including Trelissick, Bodnant and Buckland Abbey, and there have been significant developments in many others, notably at Woolbeding, Wallington, Emmetts, Nymans, Hare Hill, Seaton Delaval, Nostell, Saltram, Ightham Mote, Wakehurst and Overbecks with Berrington Hall and Baddesley Clinton poised to join them.

In an innovative departure from tradition, garden designers from outside the Trust have been commissioned to reimagine parts of gardens large areas of Beningbrough, and Delos at Sissinghurst. Participation in the Queens Green Canopy project for the Platinum Jubilee has also seen extensive tree planting, including reinstating a lost eighteenth-century avenue at Dyrham Park and recreating the pear tree arch at Rudyard Kiplings home, Batemans.

So, in spite of the pandemic years and their aftermath which have caused maintenance and staffing problems and have sometimes halted, or even reversed, the progress of restoration and the steady improvement of standards of horticulture and presentation there is much to shine a spotlight on.

For me, travelling the length of Britain, meeting the head gardeners and tapping into the story of each gardens evolution and idiosyncrasies has again been an adventure and an education. The diversity of the Trusts gardens is immediately apparent from the photographs. They range from landscape park to walled town garden, box parterre to rhododendron woodland, Derbyshire hilltop to Cornish coombe. Lakes, temples, herbaceous borders, Japanese gardens, conservatories, pinetums, swathes of daffodils, roses, regional apple varieties and eighteenth-century statues, views of sea, moor and mountain, yew trees clipped as pointed Welsh hats, it is all here.

The gardens engage you on many levels. There are the straightforward pleasures of seeing, smelling, touching, listening and exploring. For home gardeners, there are ideas and plant varieties to pick up. But go deeper and invariably you tap into a story, perhaps of great individuals and family successions, designers and plant hunters, period politics and preoccupations, changing fashions, destructions and restorations.

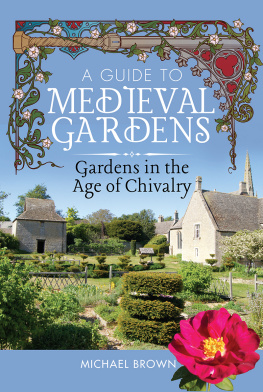

Between them, the gardens chart some 400 years of history. To medieval times there are merely brief references: in the partnership of ancient building with flowery mead at Cotehele and Sizergh, and in the presence of herb gardens at Acorn Bank and Buckland Abbey. Renaissance pleasure gardening is captured in the moated garden and banqueting house at Lyveden New Bield, the topiaries at Chastleton, the enclosures and mounts at Little Moreton Hall, the pavilion and bowling green at Melford Hall, the covered walks and knot garden at Moseley Old Hall, and, most imposingly, by the grand Elizabethan courts, gateways and finial-capped walls at Hardwick and Montacute.

The landscape movement spelled destruction for many of the great formal gardens, but those at Ham House, Westbury Court, Powis Castle, Erddig and Hanbury Hall survived in large part, or have been resurrected by the Trust, and show the European-inspired styles of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The story of the subsequent departure from these enclosed and geometric patterns and the evolution of the landscape style through its Arcadian, Brownian and romantically Picturesque phases is recounted, in whole or in part, at Claremont, Stowe, Fountains Abbey and Studley Royal, Gibside, Wimpole Hall, Prior Park, Wentworth Castle, West Wycombe Park, Croome, Stourhead, Kedleston, Petworth House and Scotney Castle.

The early nineteenth-centurys renewed enthusiasm for formality and self-consciously artful gardening is marked at Calke Abbey, Ickworth and Peckover House, with grand revivals of earlier styles displayed at Oxburgh Hall, Montacute, Blickling and Belton. The innovation, ingenuity and derring-do that became the order of the day is revealed in the fantasy evocations at Biddulph Grange, the engineering feats at Cragside and the multi-coloured parkland and bedding schemes at Ascott, while Waddesdon, Tyntesfield, Lyme, Tatton Park and Polesden Lacey give a varied and luscious insight into country-house living and gardening in their Victorian and Edwardian heyday.

The influx of new trees and shrubs from the Americas, the Far East and Australasia through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries fuelled the development of exotic woodlands, and at Killerton, Glendurgan, Nymans, Wakehurst, Bodnant, Rowallane, Trengwainton, Mount Stewart, Trelissick and Winkworth, we have supreme displays equalled later at Knightshayes and Greenway.

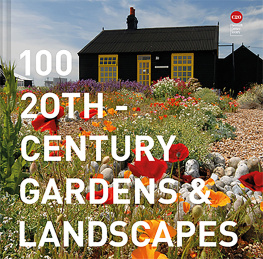

Simultaneously, architectural gardening was evolving, and in time became coupled with some dreamy and painterly herbaceous planting. Gertrude Jekylls influence pervades the gardens at Barrington Court and Lindisfarne Castle as Sir Edwin Lutyens does at Castle Drogo and Coleton Fishacre, while in the crisp compartments and sophisticated colour schemes of Hidcote and Sissinghurst the marriage of plantsmanship and formal design reaches a new twentieth-century zenith with The Homewood presenting a contrasting essay in Modernism.