BRITISH GARDENS IN TIME

THE GREATEST GARDENS AND THE PEOPLE WHO SHAPED THEM

KATIE CAMPBELL

WITH A FOREWORD BY CHRIS BEARDSHAW

Frances Lincoln Limited

7477 White Lion Street, London N1 9PF

www.franceslincoln.com

British Gardens in Time

Copyright Frances Lincoln Limited 2014

Text Katie Campbell 2014

Photographs Keo Films/Nathan Harrison 2014 except those listed on

First Frances Lincoln edition 2014

All rights reserved

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Digital edition: 978-1-7810-1150-8

Softcover edition: 978-0-7112-3576-2

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

BY CHRIS BEARDSHAW

LANDSCAPES AND GARDENS have evolved over the centuries to represent a plethora of philosophies and ideals. From the first expressions of earthly godliness and Paradise on Earth to monumental works of ego; each location feasts off a multitude of stimuli and catalysts.

These artificially crafted and aesthetically responsive gardens are the result of the collision of wealth, peace and confidence, of an individual or a nation. They are often an expression of complex factors in the form of plants, stone, water, pattern and topography, only revealing their significance through the appropriate lens.

Within each garden we can learn much from its history: about the cultural diversity and changes in fashion of ideas and concepts so many gardens responding to a world enlivened by travel and discovery. Some gardens reveal signs of cultural and artistic trends, their acceptability, interpretation and how they have been implemented. Others display political and philosophical statements heralded in monument and statuary, proclaiming allegiance to long-forgotten causes. Gardens treat us to clear representations of social structure, hierarchical class systems and the aspirations of those with unfolding opportunity and means. Through these gardens we witness fortunes made, inherited and often lost in a relentless desire to carve a statement. All of this is enabled and supported by advances in technology, deployed and harnessed to achieve the garden of ones dreams.

What is often forgotten in any cursory review of these works is that gardens are often modelled in the image of their patron, almost inevitably becoming statements and representations of the individual. As such they serve to inform and enlighten us, perhaps more than any other medium, via four dimensions, on the finer detail and nuances of the personality of the creator.

Perhaps, above all, they are fragile whispers from our ancestors to guide and inspire us in our individual advancement and pursuit of a nature perfected. It is this complexity and tapestry of content that elevates the garden from mere object of art to a running commentary on ourselves. It is also the very point that has tempted and tantalized me about all the gardens I have visited and I hope in this book the gardens draw you into a rewarding dialogue.

Chris Beardshaw

JANUARY 2014

A SHORT HISTORY OF BRITISH GARDENS

EARLY ROMAN GARDENS

Given that Britain is a country which prides itself on its horticultural prowess, it may come as a shock to discover that the first people to create gardens here were probably the Romans. While the Celts may have encouraged medicinal species to grow near their dwellings, and the Druids had their holy groves, it was the Romans who first made gardens for pleasure. Along with roads, sewers, baths and central heating, the Romans brought their horticultural knowledge to Britain. They also imported their favourite fruits and flowers, introducing to this far-flung colony such scented delights as rosemary, lavender and bay; and supplementing the native plum with cherry, pear and walnut trees. They also managed to acclimatize grapes, all-important for producing the wine that was considered the privilege of every soldier and slave.

Despite such luxuries, those early conquerors were horrified by the new colony. Their expectations were perhaps influenced by stories circulating in Rome since well before the conquest: Ovid believed the Britons painted themselves green, while Pliny the Elder thought they were stained blue; and Horace described them as more remote than anyone else in the world, as well as being very unpleasant to strangers. Julius Caesar, who first visited Britain in 55bc, claimed that nobody would be silly enough to go there except to trade, adding: many of the inland Britons do not grow corn. They live on milk and flesh and are clothed in skins. He did note, however, that while the cattle and trees were of the same varieties as those found in Gaul, the climate was milder. Britains temperate climate was indeed warmed by the northern extension of the Gulf Stream, and it also allowed the cultivation of a wider range of plants than was possible in the heat of Rome. The first-century historian Tacitus, having complained that the sky is foul with incessant rain and clouds, did concede that the soil is fertile and bears crops and that while those crops may germinate late, they shoot up quickly due to the terrific dampness of both the land and the air.

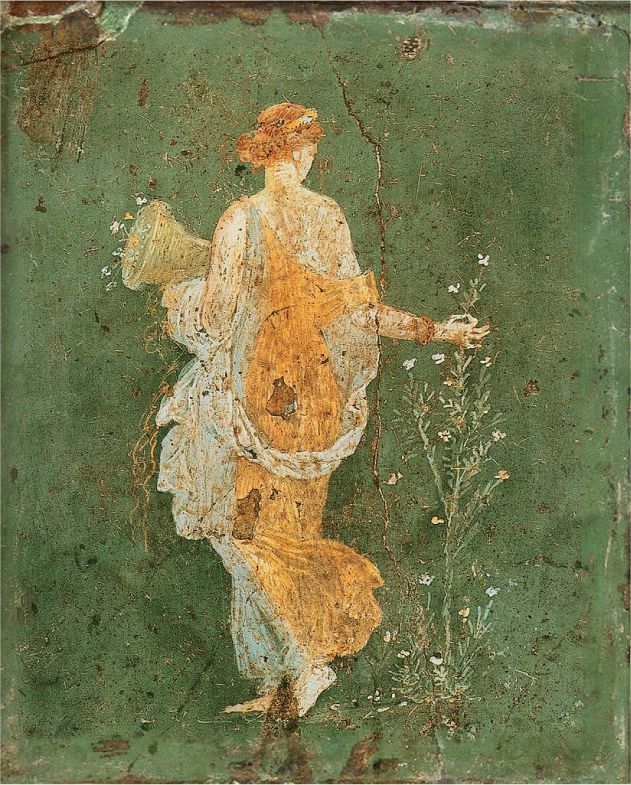

This mural found in Pompeii depicts the Roman fertility figure of Flora, goddess of flowers. Flora was honoured in the Floralia, an annual festival held in early spring to celebrate the renewal of life.

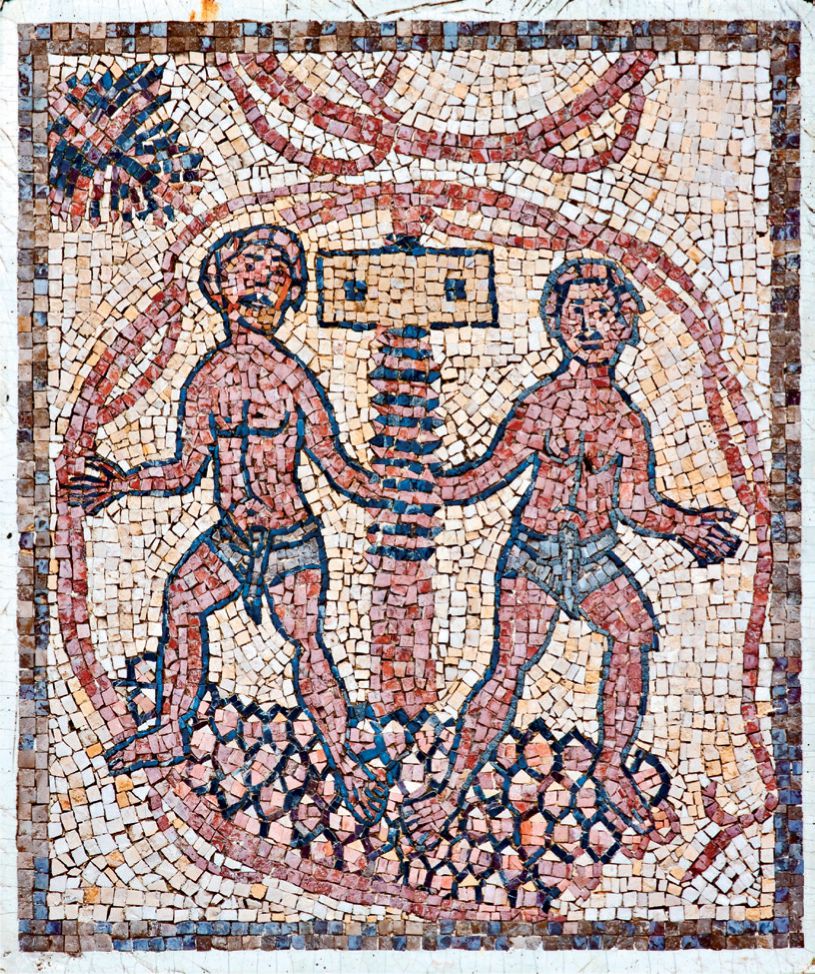

The Romans introduced wine to Britain and cultivated the first vineyards. Winemaking continued after the Roman retreat, especially in the monasteries where wine was essential for celebrating the Eucharist. The Domesday Book of 1086 records forty-six vineyards in southern England, stretching from East Anglia to Somerset; and when Henry VIII ascended the throne in 1509, England had 139 sizeable vineyards.

Even though many Roman sites have been excavated in England, archaeologists have found that remarkably little evidence of gardens has survived. One site that does give a sense of the horticultural achievements of a local ruler (but not of the people he ruled), is the first-century Roman villa at Fishbourne, near Chichester. The palace was a large rectangular building around a central courtyard. This formal space, enclosed by an elegant colonnade, appears to have been embellished with gravel paths, fountains, marble basins, decorative mosaic pavements and low hedge-lined beds for planting. There is also evidence of an informal garden beyond the palace, with trees, shrubs and streams extending down to the harbour below.