Windgather Press

is an imprint of

Oxbow Books, Oxford

L. Wickham 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means

(whether electronic, mechanical, photocopying or recording) or otherwise

without the written permission of both the publisher and the copyright holder.

ISBN 978-1-905119-43-1

EPUB ISBN: XXXXXXXXXXXXX

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

This book is available direct from

Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK

(Phone: 01865-241249; Fax: 01865-794449)

and

The David Brown Book Company

PO Box 511, Oakville, CT 06779, USA

(Phone: 860-945-9329; Fax: 860-945-9468)

or from our website

www.oxbowbooks.com

Printed by Printworks International

List of Figures

Introduction

Over the past fifty years, the subject of garden history has been firmly established as an academic discipline. While many have explored what was created in gardens throughout history, the notions as to why they were created has naturally been more diverse. Depending on the background of the author, the reasons have ranged from aesthetic values deriving from art, philosophical thoughts and ideas, social and even economic forces. Occasionally some thought has been given to the influence of political ideology, which is quite surprising given one of the earliest histories of gardening, Horace Walpoles History of the Modern Taste in Gardening, published in 1780, was overtly political. He was the son of Sir Robert Walpole, the British Whig Prime Minister for twenty-one years to 1742. However at the time of writing about 1770,

My intention with this book is to look at the creation of gardens elsewhere through a similar political lens. I thus wish to move the debate away from merely portraying garden-making as painting a picture with plants and garden buildings and explore the deeper meanings involved in their creation. What do I mean by political? The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as of or relating to the government or public affairs of a country. Specifically it relates to the ideas and strategies of a particular party or group in politics and describes actions motivated by a persons beliefs concerning politics. In this context gardens are looked at in relation to not only how they are influenced by the political ideas of their creators but also how the gardens themselves provide support and legitimacy to those in government, either overtly or indirectly.

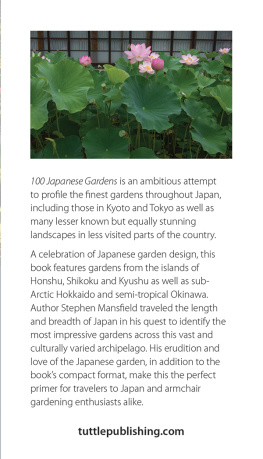

Much time and thought has been given to the meaning of the rock formations in the Ryoan-ji dry landscape garden(or more politely borrowed) but no two gardens are alike. This is the same about an individuals political views: there may be core themes that they, as part of a group, may support. So they can be labelled as holding a certain political stance, usually defined along a leftright axis but quite where they sit on this line varies depending on the subject (the economy, law and order, social issues, the environment for example). This complex interaction means that no two individuals can hold entirely the same political views on all matters.

One of the criticisms levelled at Lancelot Brown was that he created identikit landscapes with the main house in a sea of turf, some water, albeit often an impressive feature, and trees in clumps or shelterbelts. The criticism lay not in the aesthetic values of such landscape parks but rather that the owner had lacked imagination and possibly taste, an even greater crime! There was also a whiff of uniformity equating to authoritarianism. This went against the British desire for individualism that had pervaded political ideology following the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Even today with our largely uniform domestic architecture, there is that streak of individualism in the green space outside even if it is neglected and full of weeds

This is not a one-way process of politics only influencing the design of gardens. As Mukerji (1997, 35) points out gardens address some fundamental ties between human action and the material natural world, so they have surprisingly important tales to tell about human societies. Studying gardens can therefore tell us something about the political processes of the society in which they were created. Architecture and art have long been seen to have this role but the rather transitory and often ephemeral nature of gardens, has led them to be largely ignored by cultural and political historians. The fact they were often the preserve of the rich, or indeed super-rich, in the society and regarded somewhat as a frivolous pleasure, has not helped their cause. The urge to create a garden (particularly among the British!) would appear to be hard-wired into our psyche. As man developed political units in Egypt and Mesopotamia over five thousand years ago, then the first known gardens appear. These were areas where plants were grown mainly for their aesthetic value, rather than their productive abilities: a reflection both of the increasing leisure time of the leadership and the specialisation of roles within the community. At this stage too, the garden becomes part of human mythology with the concepts of the Garden of Eden and paradise as a garden becoming recurring motifs.

The early earthly gardens were designed to demonstrate the political power of the owner either by its technical achievements, for example the Hanging Gardens of Babylon,new political ideology of democracy. The only gardens in the Greek world were sacred groves, which were very natural and did not demonstrate mans power over nature. This reflected an important part of Greek philosophy, which believed that plants and men have a natural environment that shapes them (Osborne 1992, 388). Political discourse and more importantly philosophy in the Greek academies developed not in buildings but in landscaped grounds outside, so perhaps gardens can also provide inspiration to political thought!

Gardens have long been used as a means of enforcing a political culture. In this way, garden styles have crossed borders and influenced the society that they are created in. One of the earliest examples are the Persian hunting parks (pairidaeza) being adopted by the Greeks (paradeisos), giving the English word paradise and its link to the Garden of Eden. The first to actively take their cultural styles to new lands were the Romans with their expanding Empire. As far apart as Britain and the Middle East, there are practically identical styles of architecture and more importantly gardens. The latter could prove to be something of a challenge given the variations in climate between the regions and it was not only the Roman soldier but also the Mediterranean plants (Campbell-Culver 2004, 2135) that shivered in the British chill! However, added to the What Have The Romans Ever Done For Us discussion from the film Monty Pythons Life of Brian should be Apart from Gardens for Britain. The British national obsession for gardening probably started two thousand years ago, as there is no evidence of any recognised gardens in Ancient Britain prior to the Roman arrival.

The gardens of the Muslim world are an integral part of their culture and the Persian quadripartite or chahar bagh garden style that the Arab invaders adopted, can be seen with slight variations from Spain in the west to India in the east. The role of the garden as a cultural icon in Muslim society continues to this day. The local Islamic community enthusiastically embraced the creation of a Mughal style water garden, in the restoration of the previously solidly British nineteenth century Lister Park in Bradford in 2001. For the Muslims, it was not about stamping their authority on the conquered land with their style of gardening, as the Romans had done with their Pax Romana. It was about providing symbols of their religious (and

Next page