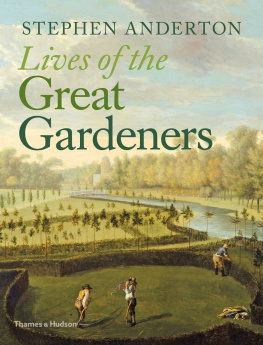

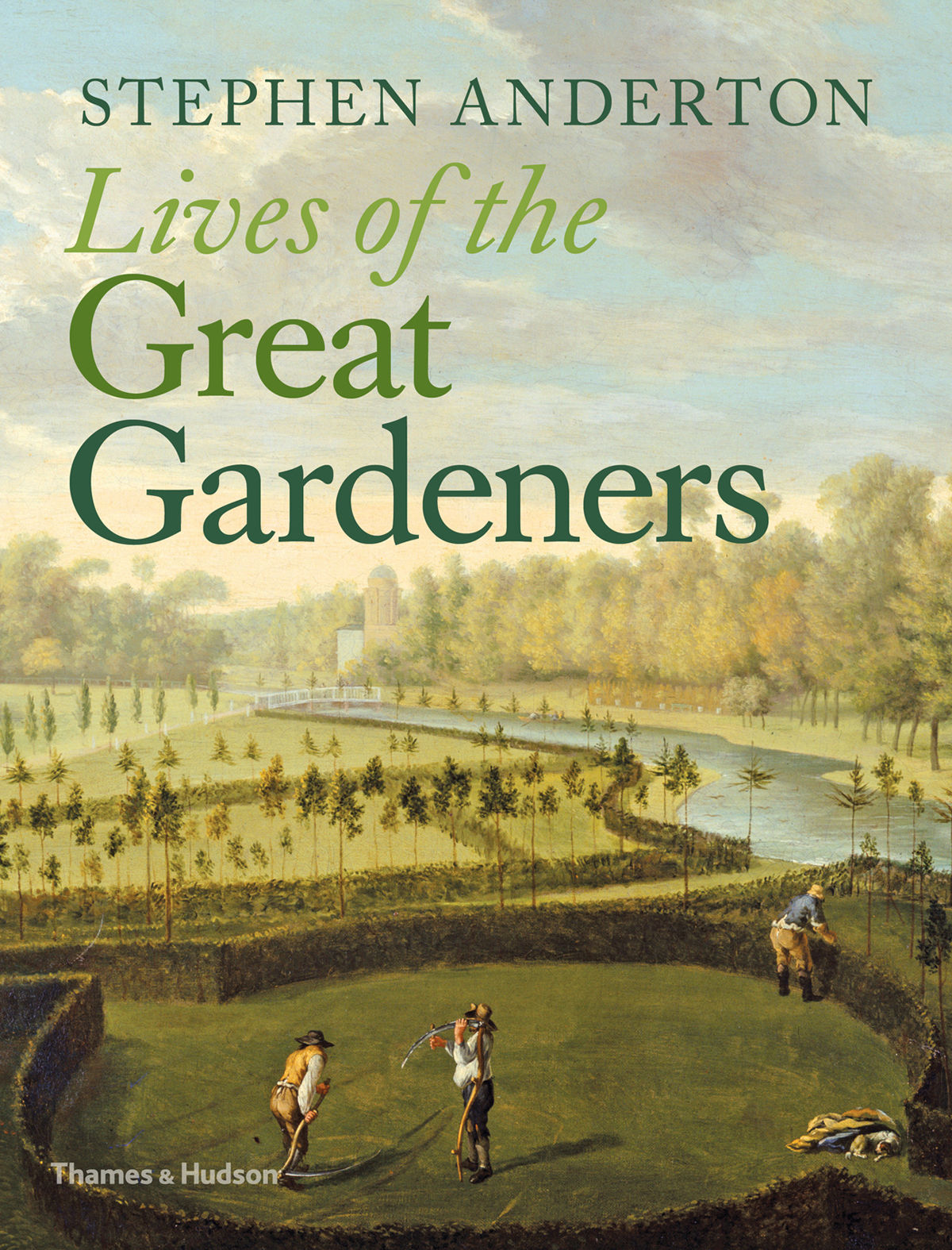

A landscape gardener with the tools, costume and apparatus of his trade, by Martin Engelbrecht, c. 1721.

I F YOU PERHAPS doubt that gardens are among the most luxurious products of civilization, just consider how many millions of people travel even more millions of miles every year to enjoy them. The greatest gardens are in fact works of art, and the world is their gallery. And, like all great art, they are priceless yet unnecessary (in practical terms); that is the wonder of them.

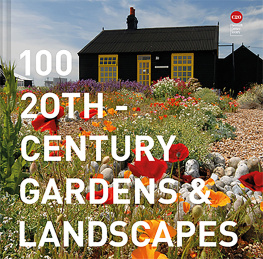

Vita Sackville-West created the famous garden at Sissinghurst, in Kent, in the mid-20th century with her husband, Harold Nicolson, and it is visited by thousands today. Vitas style of planting was one of abundance, always artfully and purposefully untidy, never too pristine.

History is full of gardens, at first vegetable gardens set close to a house and protected against wild animals or domestic livestock, or monastic and physicians gardens, walled and sometimes even moated to keep their highly valuable stock of plants secure. In the east, gardens were paradises set in desert landscapes, or philosophical and religious retreats with highly symbolic meanings and conventions. Gardens such as these existed even in lean times. In better-off times, modest ornamental gardens flourished around the houses of the rich and even the moderately well-off. Such were the cottage gardens of 19th-century Britain, so admired by Gertrude Jekyll.

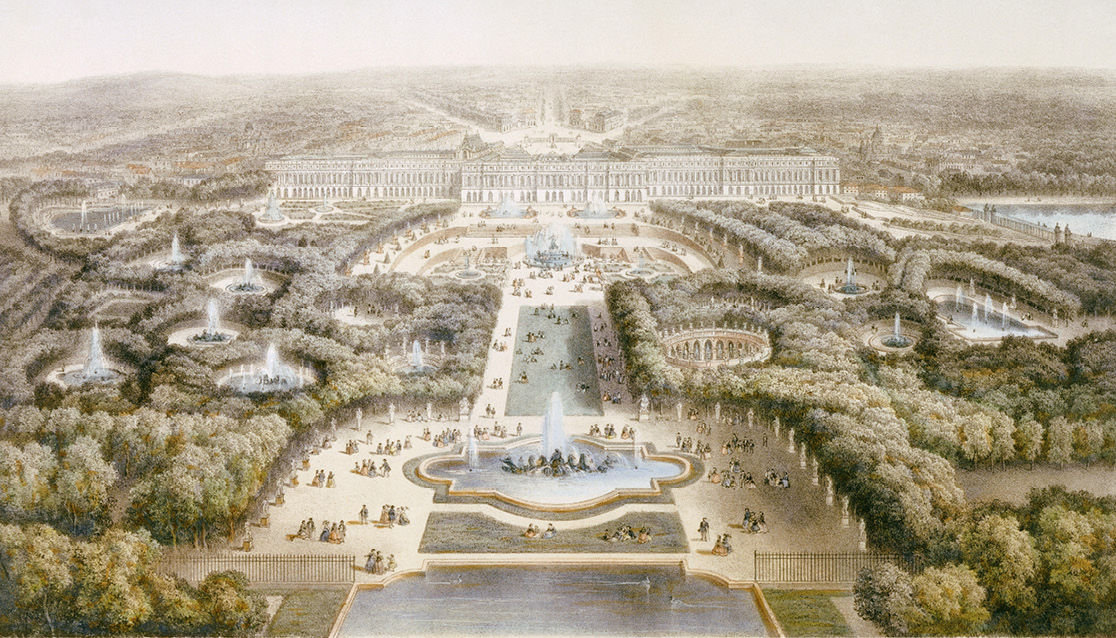

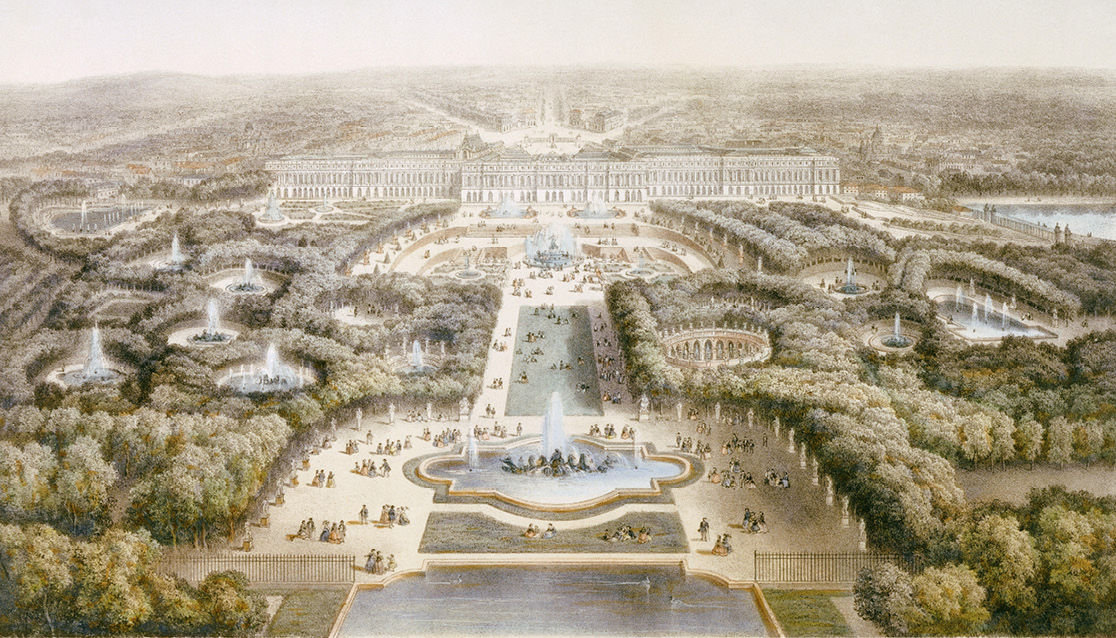

But it is when money starts to flow generously the result of imperial conquest or trade, or from long-standing aristocratic land tenure, or through the rise of a comfortable middle class that we see truly ambitious ornamental gardens. Real surplus encourages real luxury. And so as the Medici sponsored great artists to paint in Renaissance Florence, so French aristocracy and royalty and then the political classes of 18th-century Britain, rich from trade, employed talented gardeners to create their landscape gardens. Ornamental gardens demonstrated ones wealth and ones taste. But private or not, gardens are a democratic medium: those landscapes gave and still give a huge amount of pleasure, not just to their present owners, but also to anyone who sees them, from archduke to tourist to trespasser.

What sort of people make gardens? On the one hand they are people who know how to spend their own or their clients money in order to see their ideas take three-dimensional form. Some have ended up seriously in debt as a result. But its one thing to spend money and another to spend it well. Not all gardens require limitless sums, and the great gardeners of this book have the ability to match their talent constructively to their resources in order to produce a garden that is not just a collection of cameos, but somewhere of distinct character. The 18th-century landscaper Lancelot Capability Brown called himself a place maker, which might at first sound either rather dull or self-deprecatory, but in fact once you understand the principle that a good garden is a place of a unique nature, a special environment, then place maker becomes a purposeful as well as an ambitious label. It proposes that a gardener can create a place greater than the sum of its parts.

Great gardeners have come from all over the world and all kinds of background. Some have begun life in humble, manual occupations. Capability Brown, perhaps with Andr Le Ntre one of most influential gardeners ever, first worked as a garden boy on a small estate in Northumberland, a county which in the 18th century was a place remote from anywhere. Intelligent, ambitious and worldly-wise, in a very few years Brown found himself socially at ease with the greatest politicians in the land. William Robinson, the father of wild, naturalistic gardening, started life as a hands-on gardener in rural Ireland, and, through charm and determination, turned himself into a hugely successful publisher and author. If such elevations as these sound implausible, it is worth knowing that the gardening world of gardeners, designers, garden owners, botanists, nurserymen, garden historians, journalists, photographers is a delightfully small and generous one. When occasionally people move into it from high finance or the law, perhaps, looking for a second, more real career, they are amazed at its sense of good fellowship. Perhaps it is because gardeners share the recognition that each one of them will always have more to learn about plants, and that even the best, newly created garden is inescapably at the beginning of its road to decline, as plants develop and die. Gardens are a process as much as a work of art.

Andr Le Ntres immense garden at Versailles, seen here in a 19th-century engraving, incorporated strong symmetry and axes. The garden was a symbol of the order of the rule of Louis XIV; its great central vista started from the kings bedroom.

Henry Hoares Stourhead: a gravel path encircled the lake, offering views of different buildings alone or in combination. Note the way the tree canopies are kept slim and open textured to the top, to ensure good views.

Its also worth remembering that gardeners are in part salesmen, for professional designers have businesses to run and families to support. At the turn of the 19th century, Humphry Repton was notorious for the fawning nature of his entreaties for work. Even the most retiring of garden-makers must be, if not a salesman, then something of a showman.