Contents

Guide

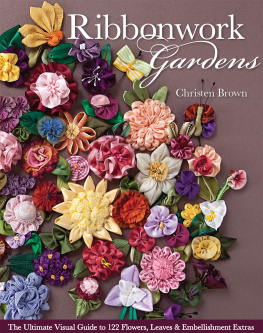

Cottage Gardens

A celebration of Britains most beautiful cottage gardens, with advice on making your own

Claire Masset

Morning light falls on one of the many narrow paths at East Lambrook Manor Gardens in Somerset.

Contents

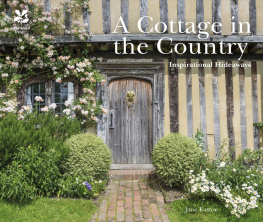

Picture a thatched cottage on a beautiful summers day. A rustic gate stands half-open, beckoning you into the front garden. In this small plot, a jumble of flowers happily grows next to rows of vegetables and fruit bushes. Wigwams of sweet peas and tall hollyhocks tower over the carrots and cabbages. As you reach the cottage door, you are greeted with the most charming of sights: an arbour covered in sweetly scented roses.

This is what springs to mind when I imagine a cottage garden. We all have our own version. Yours might be a red-brick cottage surrounded by delphiniums, lupins and daisies. Someone elses might include an old apple tree in bloom, underplanted with tulips and forget-me-nots. Each of these visions has its roots in the Victorian era, when artists perpetuated a sentimental view of rural life through evocative watercolours of English villages.

But the cottage garden is more than this romanticised interpretation. Its rich history goes back to the medieval cottagers plot. Over the centuries it has been a place of sustenance, a haven for plants on the verge of extinction, and an inspiration for designers of much grander gardens. People from all walks of life have been drawn to it from poor workers and writers, to intellectuals and aristocrats. It now represents the quintessential English garden style, favoured by gardeners around the world.

As a concept it is hard to define, but you immediately recognise it when you see it. Cosy, snug, informal, profuse, the cottage garden looks entirely at home in its surroundings, as though it has slowly evolved over time and often it has. Flowers are the stars of the show, but shrubs and topiary usually add a little structure. The cottage garden is marked by modesty. It never tries too hard to impress, for its charm lies in its homeliness.

The classic cottage garden, with its rose arch, simple path and mingled planting.

By the Cottage Gate by Helen Allingham, a typically sentimental portrayal of the Victorian cottage garden.

Many of the flowers in this front garden, such as the poppies and the red valerian by the fence, may well have seeded themselves.

In 1893, the editor of Cottage Gardening magazine attempted his own interpretation: The term is one of which it is impossible to give a definition on hard and fast lines. It cannot be confined to one class of people, because many gentlemen and ladies live in cottages We should say that a very good rule is that a cottage garden should be one in which all the labour is done by the occupier. It was exactly this last point that made it appealing to so many, at a time when paid gardening staff were starting to become less common. By the end of the Second World War very few homeowners could afford a full- or even part-time gardener.

The cottage garden style can be adapted to any garden, whether rural or not, small or large. Best of all, it allows for great amounts of self-expression; there are very few rules other than a profusion of plants, a love of flowers and a distinct lack of grandiosity. It is within everyones reach and ideal for time-poor gardeners with small plots. Even a patio or window box can become a little piece of cottage garden heaven. As William Robinson advised: Just be good to your plot, make it fertile and let the flowers tell their story to the heart. It really is that simple.

Buddleja is one of the easiest shrubs to grow and will reward you with plenty of fragrant blooms from mid- to late summer.

Hollyhocks growing at Hardys Cottage in Dorset.

Moss roses and hardy geraniums in the front garden at Hardys Cottage.

A plot of ones own

The word cottage comes from the Old English term cottar, meaning farm labourer or tenant. In return for work on the land, the cottar was given the lease of a house and a small piece of land. His plot was a place of utility. Beauty, if there was any, was a happy by-product.

Peas, beans, leeks, onions, cabbages and carrots constituted the bulk of the cottagers diet, cooked in a stew known as pottage. Commonly used to flavour ale and food, herbs were widely grown and a main ingredient in home remedies. Borage, for instance, was used as an anti-depressant; comfrey was known to heal wounds; while betony seems to have been a bit of a cure-all, helping with anything from snake and dog bites to arthritis, gout and even drunkenness. Herbal knowledge was passed down from one generation to the next, based as much on lore as on scientific fact. Rosemary, handy for headaches, colds and nervous diseases, was grown near the entrance to the cottage to ward off witches. Vervain, if planted in the garden, could help you attract a lover, for whom, once ensnared, you could concoct an aphrodisiac using the same plant.

Aromatic herbs were, of course, also valued for their scent. Mint and meadowsweet were mixed with rushes and strewn on the floor to cover up the many unsavoury odours of the cottage, where animals would frequently share the living space. Lavender and tansy were hung in bunches to repel the inevitable fleas, lice and ticks.

Meadowsweet or the Queene of Medowes, as it was described by the famous Tudor herbalist John Gerard.

Peas were a staple ingredient in the medieval cottagers diet.