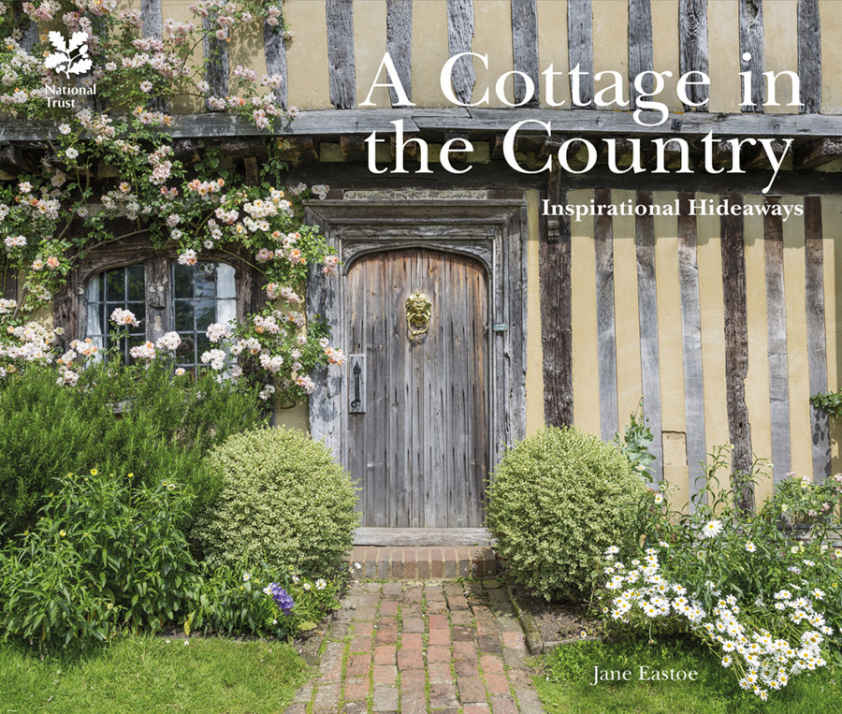

A Cottage in

the Country

A sundial in the garden at Alfriston Clergy House.

A Cottage in

the Country

Inspirational Hideaways

Jane Eastoe

Hardys Cottage.

Contents

Introduction

In July 1894 the Reverend F. W. Beynon, who had a keen interest in ancient and vernacular buildings, approached the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or National Beauty formed just ten days earlier. He wanted the charity now familiar to us as the National Trust to save Clergy House in the village of Alfriston in East Sussex for the nation. This fourteenth-century timber-framed thatched house was in a ruinous state of repair and threatened with demolition. It was to become the Trusts first property, being purchased for 10 on 16 April 1896.

Over a century later the National Trust flings open the doors of over 350 properties to 20 million visitors annually. Even its portfolio of historic holiday cottages accommodates over 50,000 visitors a year. Some, with specific historic interest, have a few weekends blocked off a year when they are also open to the public for day visits.

This architectural conservation has saved buildings that range in scale from the Palladian grandeur of Stourhead, with its 1,000 hectare estate littered with temples and grottos, to Wylam, a one-room miners cottage and the Northumberland birthplace of George Stephenson.

This book focuses on the National Trusts smaller properties, the houses, villas, lodges, homes, residences and abodes. The small, the humble and the domestic are every bit as fascinating with the patina of age as the grand stately home indeed arguably more, for they strike a recognisable chord.

These rescued cottages chart the progress of everyday lives through abject poverty to comfortable prosperity. They reveal that the notion of a cottage is open to interpretation. It can be a hovel or a palace depending on how you view it. The six-bedroom rural retreat of the well heeled is as fascinating and revealing as the charming two-up-two-down fishermens cottage that once accommodated an impoverished family of ten.

Cherryburn, the birthplace of artist and engraver Thomas Berwick, has views across the Tyne Valley.

Perhaps more than anything else it is the location that best defines our notion of a cottage, not whether it has one bedroom or half a dozen. It is a property in a desirable setting, to borrow estate agents terminology, with views over the countryside, river or coast. It might have been constructed out of necessity like Fen Cottage on Wicken Fen in Norfolk, which had duckboards in the bedrooms in case of rising water. It may have been created out of idealism like Rosedene in Worcestershire, a Chartist experiment to help working men obtain the vote. It could have been built purely for pleasure, such as the Hollywood Spanish Portland House in Weymouth, which was constructed in the 1930s for Geoffrey Henry Bushby, a bachelor with a private income.

These fascinating slices of social history reveal that despite our preoccupation with our homes, our tenure is very often short-lived. Each generation extends, alters and improves according to necessity, fashion and finances. We knock down, and rebuild, and our homes evolve with us, changing according to social strictures, the whims of fashion and personal fortune. Our tenancy, with the odd exception, is transitional.

Even the peg hooks at Arts and Crafts inspired Stoneywell show attention to detail.

The National Trust property of Townend, in Troutbeck in the Lake District, is a prime example of just such a rarity. This home remained in the same family for 400 years and through 12 generations passing from eldest son to eldest son, eight of which were named George Browne. Only after a family member finally spurned their inheritance in 1943 Townend had neither running water nor electricity did it come onto the market for the very first time.

Such constancy is rare; as a nation the British move at speed, embracing new ideas and trends, and discarding all that is outdated. A dairy or stable is built and later transformed into a garage or workshop. A beautiful garden is designed, dug over as a vegetable patch in extremis , before being restored to former glories. We dismiss our parents old-fashioned lifestyles and dcor, but by the end of our days we look back with nostalgia, and realise that so much of what has gone before has been erased and lost. Even the sturdiest building has a natural lifespan.

Repair, restoration and conservation require time, effort and money. As properties age, the financial burden and upkeep becomes too much to bear. This is where the National Trust steps in. The Trust aims to conserve our architectural heritage, preserving properties so that we can remember the lifestyles of the great and the good, to absorb the atmosphere of days gone by, and to remind ourselves how quickly our common history changes and adapts, and how easily we forget that others have trod the way before us.

Much of the National Trusts vast property portfolio has been bequeathed to ensure the preservation of precious historic homes, often after long, costly, personal conservation battles. The Trust aims to decide how best to utilise the asset, while simultaneously protecting and preserving its existing features. When restoring a historic property, how best should it be shown? Deciding whether it should be restored back to its original state or if there is a place for the 1930s kitchen equipment and the 1950s toys which also have their place in the story of the property is a difficult, but important, undertaking.

The National Trust takes a view and it is its aim to preserve tiny pockets of our past. The cottages described in this book remain our legacy, a reminder of who has gone before, sometimes the first owner, and sometimes the last. They mark lifestyles long past, hopes abandoned and dreams fulfilled, a reminder that our homes are so much more than bricks and mortar.

WORKERS COTTAGES

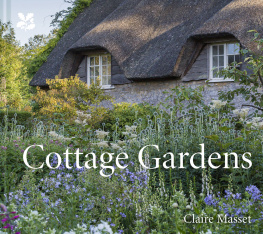

Alfriston Clergy House

Alfriston, East Sussex

This Wealden timber-framed, thatched house was built around 1350, in the reign of Edward III, by a yeoman farmer who somehow prospered after the Black Death. With two-story jettied wings, the oak frame is in-filled with laths and a lime-wash daub or, where repairs took place, a late Victorian cement render. The hall floor is made from a mix of rendered chalk and sour milk. In 1395 Michelham Priory was granted the Clergy House, as it later became known. After the Priory was dissolved in 1538 and a brief ownership by Sir Thomas Cromwell, the house became a rectory. During later years the Church rented it out as a source of income.