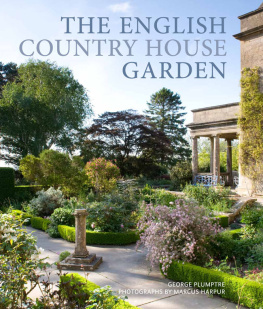

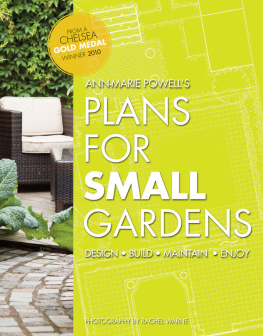

THE ENGLISH

COUNTRY HOUSE

GARDEN

The house at Goodnestone Park overlooks the Millennium Parterre.

The Canal Garden at The Old Rectory, Naunton was designed by Dan Pearson.

THE ENGLISH

COUNTRY HOUSE

GARDEN

GEORGE PLUMPTRE

Photographs by

MARCUS HARPUR

CONTENTS

Piet Oudolfs perennial meadow, the centrepiece of the Walled Garden at Scampston Hall.

T he purpose of this book is to complete the jigsaw that is the English country house garden so as to bring together all the contributing strands and show a picture that is more than just a compilation of the gardens included. It is to present a whole that is more than just the sum of the parts parts that are individually attractive but usually presented in isolation, not bound together to present a story. To many readers the subject might appear predictably familiar; country house gardens are constantly beckoning from the pages of glamorous-looking books and they are the staple diet of Country Life and other magazines at the quality end of the newsagents rack. In addition, the country house label has social connotations that are not entirely twenty-first century. It begs the question asked in a recent book by Christopher Woodward: Why does the country house continue to be the apex of a designers aspiration, rather than the small garden or the park?

Trade will always follow the market, and so, if the most financially and professionally rewarding commissions for designers are forthcoming from the owners of country house gardens, then that is where they will go. Over and above this commercial certainty, it is possible to demonstrate the intrinsic significance of country house gardens. Through many centuries they have most often provided the instances where gardens have been made with these crucial elements: a central partnership between a house and its garden; the wider relationship between this partnership and surrounding landscape; a clear human element; and then the detailed ingredients of planting and architecture, water and ornament.

Helmingham Halls long south facade faces across the moat to the Parterre and the Walled Garden beyond.

These fundamentals have underpinned most of the great gardening traditions throughout history, from Ancient Persia, to the Italian Renaissance, China and Japan. Because of its extraordinary longevity, however, the English country house garden has proved a unique canvas both for continuity and diversity. It has shown itself suitable for the full range of garden styles, like an art gallery where religious Old Masters hang alongside life-like portraits, romantic landscapes and abstract contemporary installations in an eclectic yet somehow harmonious whole. The achievement of such harmony is a driving theme of this book.

Secure with the richness of visible, tangible ingredients that it has been able to offer, the country house garden has evolved to satisfy our aspirations and longings. The garden is seen as a place of sanctuary, so dear to Vita Sackville-West among many others. It is also a place that is able properly to celebrate a naturalistic approach and respect for the environment, where you can experience accessible, rural tranquillity. A country house garden may unveil a historical story and, with it, a sense of establishment that is both intriguing and comforting. Contrastingly, as has been the case in many recent instances, it has proved to be a place where the startlingly modern and new has been introduced to vibrant, rejuvenating effect. All of these are significant parts of the jigsaw, as much as individual plants and their combinations, or the different design features favoured from one period to the next.

Like many aspects of human activity, the English country house garden has developed a select group of role models. Three gardens stand out as essential, and the book opens by describing and examining what it is that has made this trio so widely admired and aspired to. The spotlight of fame that such reputations bring is not always a kindly one and encourages the inevitable debate over the appearance and management of these places. As a result of their status as paragons, they are at risk of being over-scrutinized. But beneath the ebb and flow of opinion there are very real and lasting characteristics and qualities that people continue to seek both to enjoy and to emulate. Perhaps most significant in judging their reputations, they seem to have attained a position within the flowing evolution of our gardens that is constant. They were acclaimed as encapsulating the best principles of garden making when they were being created, and a century later they are still judged to be equally relevant to garden making today.

The Water Garden at Kiftsgate was created in 1999 on the site of an old tennis court.

Lutyenss outstanding architectural features at Folly Farm, such as his sweeping flights of circular steps down into the Sunken Garden, have been retained in the recent rejuvenation of the garden to designs by Dan Pearson.

It is important to grasp the historical progression of gardens and their partnership with houses, so a selection of eminent gardens from different centuries has been chosen to fulfil this aim. We can see the differences both in style and motivation from one period to another at the same time as appreciating how the country house garden of today has this inspiring pedigree behind it. Also how, with the long passage of time, past styles of gardens have been revived and championed. As a result, many gardens that apparently have been created within the last two or three decades clearly embrace the example of their predecessors. In so doing, they give themselves an integral sense of establishment that can subtly complement their newness or modernity. In other places, a long history has involved a tale of mixed fortunes which, when it results in recent restoration and security, is even more to be celebrated.

There is definitely a country house garden ideal. It involves a happy marriage of the visible and the intangible, and is currently exemplified in a variety of gardens. It is something of which people are aware and enjoy when they visit these gardens and which they perpetuate through the memories that they take away. Like any good garden, horticulture and design are part of the recipe, but they are never the whole story, and from place to place the combination of ingredients varies with beguiling subtlety.

Country house gardens celebrate the human element in gardening and in some cases they powerfully illustrate one persons dream or achievements. The creation of the garden implies great personal involvement and satisfaction, and this symbiotic bond between a person and their garden is endlessly fascinating. Thus, a comparison of a selection of places where this is evident adds a strong theme to the overall story.