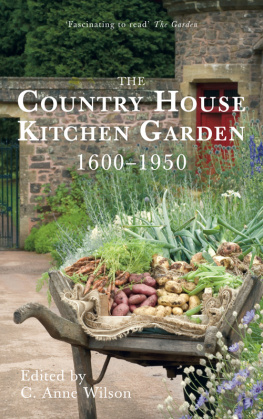

Most of the illustrations not separately acknowledged in their captions have been reproduced from books in the Brotherton Library, University of Leeds; and the editor and contributors would like to thank the former University Librarian for granting us permission to include them in this book. We are most grateful to Chris Copp of the Staffordshire County Museum at Shugborough for providing us with copies of original photographs now housed there; and to Margaret Willes and the staff of the National Trust Photographic Library for selecting and lending photographic material from National Trust properties for reproduction in the book. Our thanks are also due to Miss Cheryl Bates for the information on Shugborough drawn from her survey of 1984, and to Peter Brears for permission to reproduce his drawing of A grand sallet.

C ONTENTS

by C. Anne Wilson

T HE G ARDEN

| Susan Campbell |

| Malcolm Thick |

| Simone Sekers |

| C. Anne Wilson |

| Susan Campbell |

| Todd Gray |

| Una A. Robertson |

T HE P RODUCE

| C. Anne Wilson |

| Joan Thirsk |

| Layinka Swinburne |

National Trust Properties:

Susan Campbell has studied the history of country house kitchen gardens for over 20 years. She is author of Charleston Kedding (1996) and A History of Kitchen Gardening (2005), and advisor for the recently established kitchen garden at Tatton Park.

Malcolm Thick has written many articles on the history of food and commercial gardening, and also a book about market gardening around London. His latest book is Sir Hugh Platt: the Search for Useful Knowledge in Early Modern London (2010).

Simone Sekers has written on food and kitchen gardening in books and articles, and as a Sunday Telegraph columnist. She is author of The National Trust Book of Fruit and Vegetable Cookery (1991). She is an active supporter of Common Ground.

Todd Gray researches regional local records, including historic garden records, in south-west England. He has published articles, monographs and books, including those brought out by his Mint Press in Exeter. He is author of The Garden History of Devon (1995).

Una A. Robertson is a freelance historian with a special interest in Scottish domestic history. She is author of Coming out of the Kitchen; Women beyond the Home (2000).

Joan Thirsk was Reader in Economic History at Oxford University from 1965 to 1988, and is well known as an agricultural historian and editor. She is author of several books, most recently Food in Early Modern England, 1500-1760 (2007).

Layinka Swinburne has published articles on food history. Her research interests include medicinal receipts occuring in manuscript receipt books, and their relation to ideas on health and nutrition.

C. Anne Wilson , formerly an Assistant Librarian at the Brotherton Library, Leeds University, is a freelance food historian. She has published many articles and her books include The Books of Marmalade (revised edition, 1999) and Water of Life (2006)

C. A NNE W ILSON

This book forms a companion to The Country House Kitchen, 16501900 , a double volume edited by Pamela A. Sambrook and Peter Brears and first published in 1996. Both books originated from three theme-linked meetings of the Leeds Symposium on Food History held in the April of 1993, 1994 and 1995, where the themes were, in turn, the food-producing offices which supported the country house kitchen; the kitchen itself; and finally the kitchen garden and its produce. The meeting centred on the kitchen garden, held in April 1995, provided a rare opportunity for garden historians and food historians to get together and learn more about each others special areas of knowledge.

The talks given on each occasion had to be fitted into a single day, so inevitably some aspects of the subject could not be covered. For the present volume extra chapters were commissioned from historians with expertise in the relevant fields to help us to fill the gaps and present a well-rounded account. Susan Campbell has added a chapter on frames and greenhouses for protecting exotic fruit and tender vegetables; and Todd Gray has written one on the growing of wall-fruit in the West Country of England. Una A. Robertson has provided a survey of the development of kitchen gardens in Scotland; and Simone Sekers a detailed picture of the kitchen garden arrangements of one English country house: Shugborough in Staffordshire. The other chapters were written by the speakers at the original Symposium meeting, and follow the lines developed in their talks then. The only exception is the chapter on Growing Aromatic Herbs and Flowers for Food and Physic, added by the editor because the speaker at our meeting had focused on modern herb gardens developed at country house properties since 1970.

C. A NNE W ILSON

This book is about the vital contribution from the garden to the provisioning of the country house during earlier centuries. The service buildings of the country houses of Britain have attracted a good deal of attention in recent years. In some of the former laundries, dairies, bakehouses and brewhouses enough of the original layout and equipment has survived to enable them to be restored with a fair degree of accuracy. However, the same cannot be said of that other great service area, the kitchen garden. The walls may still stand, and some of the greenhouses and frames may still exist, if only in a dilapidated state. But the arrangement of beds and borders disappeared completely once it ceased to be an economic proposition to manage the gardens according to earlier practices.

In former times such gardens supplied a large household with fruit and vegetables throughout the year. Now that household has shrunk. Country house families are smaller, and the previous array of domestic servants has dwindled to just a few helpers. Furthermore, the expense of the upkeep of the house itself has become such a burden that few owners would wish to maintain in addition the numerous heated glasshouses of the Victorian era, or to meet the wages bill for staff to grow exotic fruit and vegetables there year round. Nor is there any reason to do so, when the same exotics are widely available from greengrocers and supermarkets at a fraction of the cost of raising them in the British climate.

Though the former patterns of cultivation have disappeared, we can still gain a very good idea of how the beds and borders looked and how they functioned from the gardening manuals published from the later sixteenth century onwards in response to a keen demand from country house owners. Through these books we can trace gradually changing fashions in kitchen gardening. Visual evidence exists too, from several periods, in the form of engravings of individual gardens made as a record for the families who owned them.

Garden planning has been a popular activity in Britain for a long time. At first the gardeners tended to follow the practices of the Dutch and the French. But the many innovations introduced through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries meant that Britains kitchen gardens attained standards of excellence unsurpassed anywhere in continental Europe.

The kitchen garden at all periods was surrounded by walls, fences or hedges. These were useful in keeping out thieves both animal and human. But an additional advantage was that they created a sheltered area with its own microclimate where vegetables and fruit trees could flourish.

Next page