I Have Been Assigned the Single Bird

ALSO BY SUSAN CERULEAN

Coming to Pass: Floridas Coastal Islands in a Gulf of Change

Tracking Desire: A Journey after Swallow-tailed Kites

UnspOILed: Writers Speak for Floridas Coast (edited with Janisse Ray and A. James Wohlpart)

Between Two Rivers: Stories from the Red Hills to the Gulf (edited with Janisse Ray and Laura Newton)

The Wild Heart of Florida (edited with Jeff Ripple)

The Book of the Everglades (editor)

Florida Wildlife Viewing Guide (with Ann Morrow)

Guide to the Great Florida Birding Trail: East Section (edited with Julie Brashears)

Planting a Refuge for Wildlife (with Donna LeGare and Celeste Botha)

I HAVE BEEN ASSIGNED THE SINGLE BIRD

A Daughters Memoir

Susan Cerulean

The University of Georgia Press Athens

Some personal and place names have been changed throughout the book to protect the privacy of the individuals and institutions involved in this story.

Image on : Adobe Stock | Leonard

Images on : David Moynahan

2020 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Designed by Erin Kirk

Set in 10.5/15 Fournier

Printed and bound by Sheridan Books

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 C 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Number: 2020003819

ISBN : 9780820357379 (hardback : alk. paper)

ISBN : 9780820357386 (ebook)

For Jeff, life companion

and

For Bobbie, Irish twin

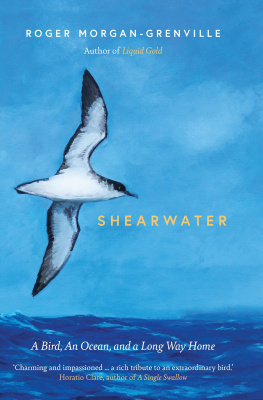

I Have Been Assigned the Single Bird

Looking after shorebird nests on an island in Apalachicola Bay.

Photo by the author.

Prologue

Our bodies return our bones to the Earth in many ways. For some, strokes and hemorrhages ricochet like a sort of internal lightning inside the brain or through the heart and arteries. Such was my fathers fate, and for him, those strokes led to dementia and a long decline. It fell to me and my husband, Jeff, to care for that sweet man during the last five years of his life. As many people do, we struggled to reconcile the minutia of the bedside with our full-time work, with three sons to raise, and with the urgent call to speak and act on behalf of our climate and the besieged wildlife of Florida.

The writer William Kittredge once said: I dream of the single-hearted heaven that is the coherent self.

In the face of dementia, a coherent life for any of us seemed out of the question. Jeff and I knew that if we took my dad into our home, the chaos dismantling his brain and body would overwhelm us. So we rented a room in an assisted living facility only a mile away, and there we saw to his care.

One afternoon, during the second September of my fathers stay in the nursing home, I stood near his bed and pressed my forehead against the window. Through the glass, I could hear the muffled calls of cardinals and red-eyed vireos. I did not open the windows, for the late summer air steamed like a thick hot pudding.

When we first moved Dad into that room, the emerald light filtering through the windows had reminded me of swimming underwater in a warm river. It wasnt really so bad, like you might fear kudzu-mediated sunlight could be. But as time passed, I noticed that many of the tall pines around the nursing home were dying under the weight of the vines swarming their living canopies. I saw that those smothering lianas were like the tangles and plaques in my fathers brain, how both kudzu and Alzheimers replace a vibrant living placea brain once full of inborn competence and memories of long-gone houses and long-grown childrendissolve those things in super-slow motion, replacing them with loss. Dads drugs, the Namenda and the Aricept, were like winter frost in the forest. For a time, they would keep the plaques in his brain at bay. Link by link, the invasive vines weighted that scaffold of mature trees with blankets of biomass. I could still make out the biggest magnolia setting its red fall fruit, but I didnt know if it would survive until freezing December nights slashed the tough kudzu back to its knees.

During the time we cared for my father, I began to volunteer as a steward of wild shorebirds on several islands along the north Florida coast.

Two or three times a month between March and August, Id slide my kayak down the concrete ramp at Ten Foot Hole in Apalachicola.

Id tidy my lines, floating in the backwater basin between a double row of houseboats, sailboats, party boats, deep-sea fishing boats. I came to know them like I did each home on my own street in town. Some of the sailors and anglers recognized me too. I liked to imagine I was becoming part of the place, the background, not on a first-name basis, but worth a nod, not a startle. The fisher folk might not have known where I was going or what my job was, but I felt as if I were a moving piece of the working waterfront. Not a tourist.

My territory was a tiny island just south of the Apalachicola bridge where I was to locate and keep track of any birds nesting on the small, tear-drop-shaped island: most likely candidates were least terns, black skimmers, certain small plovers, or American oystercatchers.

Id line up the prow of my boat with the red channel markers and adjust to the tide and the rivers wide current. Then Id push my shoulders into my double-bladed paddle and align with a mindset that might make me as much a part of the scenery on my upcoming bird survey as I was among the people of the boat ramp. That was my goal. Otherwise, as I entered the birds nesting ground, I would be perceived as a threat. I imagined fading into quiet, becoming background, being benign. I am a simple being, only passing through. I have a familiar aspect and trajectory. Dont be afraid, not of me. I cloaked myself in that mantra.

Very quickly I found a single oystercatcher brooding her eggs on the sand. Over her long orange dagger of a bill, through scarlet-rimmed eyes, she had been tracking my approach long before I saw her. Her eye saw my paddle slicing the quiet waters of the boat ramp, watched my path unfolding, even before I myself had ascertained the mood of the wind. Never should I think that my eyes are brighter and more alert than hers, she who has sifted into this landscape every day of her life, and every day of the lives of her kind, for millions of years. From that long perspective, she watched me from her nest scrape on the sand. Three eggs burned into her belly through her brood patch. Her job was to watch for danger.

Was I danger, was I really?

Need her pulse sharpen, need she spring off the nest and expose her eggs to the sun in order to draw my eye off the little shingle of beach that was home for her shell-bound brood?

Correct. Yes. Absolutely.

Yes. Our human selves are a grave danger to everything wild and vulnerable on the planet.

I didnt know the Earth was afflicted by our species until I was well into my twenties. All I wanted to do was submerge myself in the delight of it, and I did: the Atlantic Ocean, cold and dark and irresistible. Piles of autumn leaves: scarlet, orange, cadmium yellow. Canoe expeditions through the pitcher plant bogs of the Okefenokee Swamp and the chill of the Suwannee Rivers springs. I took those wild places and the reliable turn of the seasons for granted. Excesses of winter simply meant a pair of snow days; summer, a brief wave of heat. There was no reason to imagine the seasons would ever lose the structure they offered my life. The natural world was mine to dwell on, and I did.

Next page