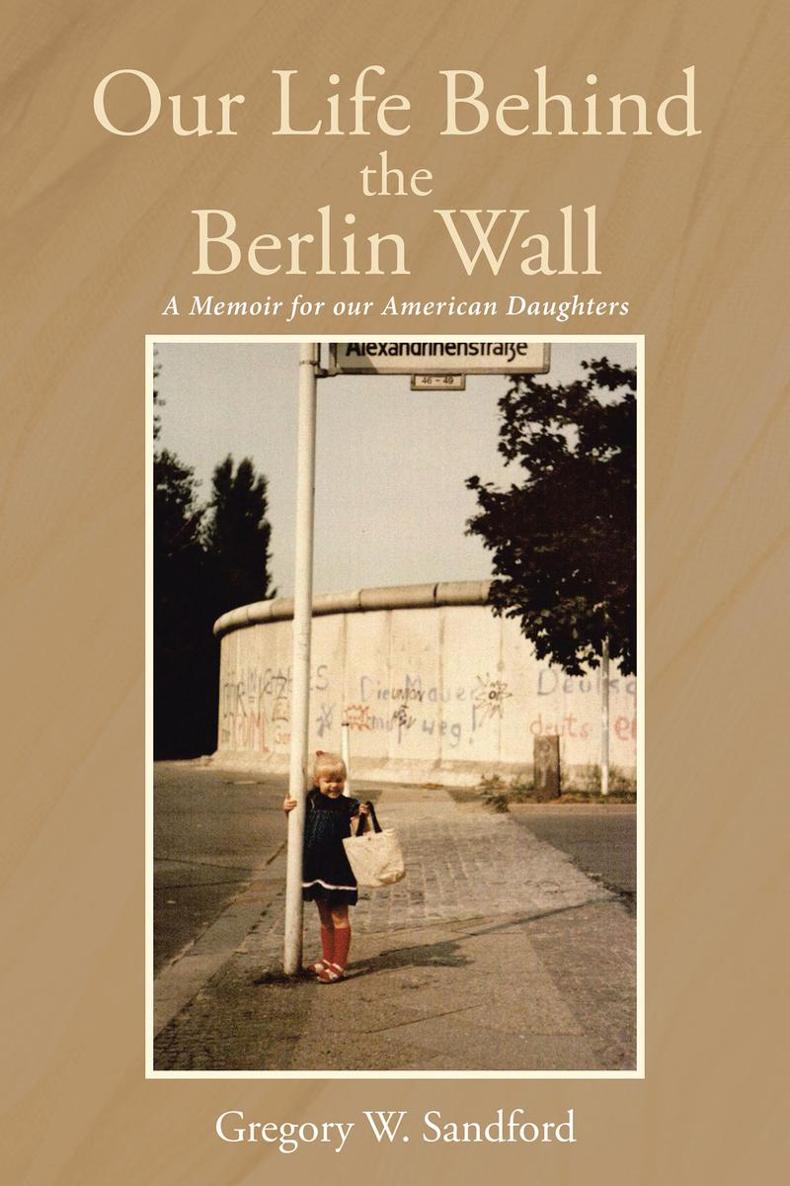

Our Life Behind the Berlin Wall

A Memoir for our American Daughters

Gregory W. Sandford

Copyright 2020 Gregory W. Sandford

All rights reserved

First Edition

PAGE PUBLISHING, INC.

Conneaut Lake, PA

First originally published by Page Publishing 2020

ISBN 978-1-6624-0360-6 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-6624-0362-0 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-6624-0361-3 (digital)

Printed in the United States of America

Table of Contents

To Ariane and Jeanine

When you were little in East Berlin, I often wondered how I would someday explain to you and your children the strange world we were living in at that time. This book is my attempt to do so.

And to Nancy

My partner in all these events and my collaborator in this book.

I

Some Context

The four of us arrived in East Germany in August of 1984: you two girls, your mother, and I. On our first morning behind the Wall, we took a stroll around our new neighborhood in central Berlin. Walking toward Checkpoint Charlie, the main crossing point to West Berlin, we happened on a subway station that was permanently closed. I was able to explain the situation to your mother, having spent several weeks in East Berlin a few years earlier on an academic exchange program. Two of the prewar underground lines that began and ended in West Berlin crossed under East Berlin, so when the Wall went up in 1961, the East Berlin stations were all sealed. The next station was in West Berlin and was open. This was one of many poignant reminders of the strange and cruel fate of this divided city at the heart of a divided country and a divided Europe.

To understand our life as Americans in East Germany, you first have to understand the situation of Berlin and Germany in the 1980s. At the end of World War II in 1945, the victorious Allied powersthe United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Unionsplit up Germany into separate occupation zones that were initially intended to be temporary. However, by 1949, with the Cold War deepening, the three Western powers had unified their zones into the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), while the Soviets had created what they called the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in their zone. The two German states developed political and economic systems modeled, respectively, on Western-style democracy and Soviet Communism.

Berlin, the capital of prewar Germany, had been intended to serve as the seat of a joint Allied administration for all of Germany. Each of the four Allied powers controlled its own sector of Berlin, which lay a hundred miles within the Soviet Zone. Each of the Western Allies had agreed-upon access routes to its sector by land and air from West Germany. As cooperation descended into East-West confrontation, however, Berlin itself became divided into East and West Berlin. That division became concrete, literally, with the erection of the Berlin Wall by the GDR in 1961 to stop the flow of East German refugees to the West.

As East-West relations deteriorated, the existence of a Western outpost so deep inside the Soviet Zone was unwelcome to the Soviets, and they and their East German comrades made repeated efforts to force the Western Allies out. The first and most dramatic of these was the Berlin Blockade of 194849, in which the Soviets attempted to cut off the Allied access routes to the city, and the Western Allies responded with a Berlin Airlift that successfully demonstrated their determination to defend their rights there.

In the early 1970s, a series of agreements among the four Allied powers and their two German client states resulted in international recognition for the GDR, including exchanges of diplomatic missions with Western powers, that had previously been withheld. The status of Berlin was also regularized, but in a way that incorporated continued differences over Western rights there. By that time, the Soviet Union claimed to have granted the GDR sovereignty over East Berlin, and the GDR had begun to refer to the eastern sector as Berlin, capital of the GDR. The Western powers never accepted this claim and continued to insist on four-power sovereignty over the city with rights of access for all four powers to all four sectors. They demonstrated this by daily military patrols through the Soviet sector and by recognizing corresponding rights for the Soviets. These rights applied to all official representatives of the Allied powers, including diplomats like me. They did not, however, apply to average citizens, who were subject to regulations imposed by the respective German authorities in Berlin.

By the 1980s, a kind of game had developed between East and West in which the GDR authorities would try to whittle away at Allied claims of sovereignty in a variety of subtle ways. They repeatedly presented Western embassies with documents describing us, for example, as the American Embassy in the German Democratic Republic, which we would correct to the American Embassy to the German Democratic Republic in Berlin, to emphasize that Berlin was not in the GDR, regardless of where the GDR government chose to put its offices. East German officials consistently referred to the sector boundaries between East and West Berlin as borders, tried to make them look like international borders, and were eager to get their hands on Allied passports so that they could put a GDR immigration stamp in them. Hence, our instructions as U.S. diplomats were never to allow this but, instead, to cross the sector boundaries by car, showing the GDR officials there the information pages of our diplomatic passports through a closed window. If the GDR border police objected to this procedure, we were to insist on speaking immediately to a Soviet officer.

II

Welcome to East Germany

Because of the complexities of Berlinery, our initial arrival had to be by a roundabout route. If we had tried to cross from West Berlin to East Berlin before being formally accredited as diplomats by the GDR, the East Germans might have tried to stamp our passports at the sector crossing point, and our acceptance of this stamp might then have been exploited as evidence that the U.S. did, in fact, recognize East German sovereignty within Berlin. To avoid this, we had to fly into Schoenefeld airport, just outside Berlin in territory indisputably belonging to the GDR, where we could accept such a stamp without any implications for Allied sovereignty rights. Since no American carrier flew into Schoenefeld, we arrived on KLM by way of Amsterdam.

First Impressions

Our fellow passengers provided an early experience with one feature of East German society. Sitting behind us were two young women who were charmed by our little daughters and began cooing over them as women might anywhere. They were built like linebackers. They told us they were East German swimmers returning from a competition, and they had evidently been subjected to a regimen of steroids as well as strenuous physical training. The contrast between their very feminine behavior and their very masculine appearance was striking and rather pitiful.

What happened next only became completely clear years later when the government of united Germany gave us access to the file kept on us by the GDRs Ministry for State Security (nicknamed Stasi). There we found photos taken secretly of our arrival, showing us and our girlsat that time one and four years oldbeing greeted by colleagues from the U.S. Embassy. We also found copies of letters and documents from my briefcase, quickly photographed by GDR authorities as they checked our luggage. (We had made sure that nothing sensitive was in there.)