Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2015 by Deborah Cramer. All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Maps by Bill Nelson. Illustrations by Michael DiGiorgio.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cramer, Deborah.

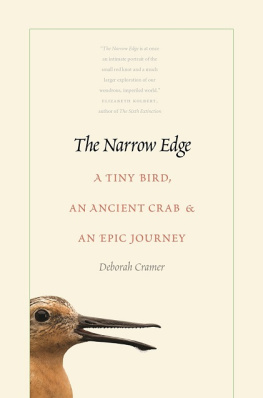

The narrow edge : a tiny bird, an ancient crab, and an epic journey / Deborah Cramer. pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-18519-5 (alk. paper)

1. Red knotMigrationDelaware Bay (Del. and N.J.) 2. Shore birdsMigrationDelaware Bay (Del. and N.J.) 3. Migratory birdsDelaware Bay (Del. and N.J.) I. Title. QL696.C48C48 2015

598.15680916346dc23 2014040788

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO A BBY , S USANNAH , AND D AN WITH LOVE AND MANY THANKS

T O J UDITH C RAMER

F OR HER SUPPORT FROM THE BEGINNING, NOW SO LONG AGO

In memory of

P ETER D AVISON

P AUL E PSTEIN

C AROLINE N EWMAN

H ARRIET W EBSTER

T ERESA H OPPER L ACHANCE

Contents

Beginnings

O ne warm May night, around midnight, I drove out to an empty beach on Delaware Bay. The summerhouses nearby were dark and empty, the only light the full moon shining on the bay, and the only sound the waves gently lapping against the sand. Just before high tide, horseshoe crabs began emerging from the water. Their shells, some as large as dinner plates, were dark and scuffed. These prehistoric animals, emissaries from the deep sea, were coming in to lay their eggs in the sand. Id never seen anything quite like this. I used to go down to the edge of the creek near my home in Gloucester, Massachusetts, to look for spawning horseshoe crabs, their unfailing arrival sign that a hard winter was turning to spring. There were never very many; at most Id find six or eight. Delaware Bay is home to the worlds greatest concentration of horseshoe crabs. On this beach, they came by the thousands, gliding effortlessly through the water, then burrowing in the sand. When the tide turned, they surfaced, slid into the waves, and disappeared. If Id been at the beach an hour earlier or an hour later, Id have missed them.

The next day more wildlife amassed on Delaware Bay beaches thousands upon thousands of migrating shorebirds, an avian Serengeti, one of the greatest concentrations of shorebirds on the eastern seaboard of the United States. The birds remained in the bay for only a few weeks: for many years, ornithologists didnt seem to know they were passing through. Theyd come for the horseshoe crab eggs in flocks so thick I couldnt see the sand. Among them were a few thousand russet-colored sandpipers, red knots. They raced along the shore, frantically grabbing scattered horseshoe crab eggs. Where had the knots come from that they were so desperately hungry? And how could a diet of tiny eggs, each the size of a pinhead, take them where they were going? They wasted no time: theyd flown more than 7,500 miles to get here, and in two weeks, theyd be flying 2,000 more.

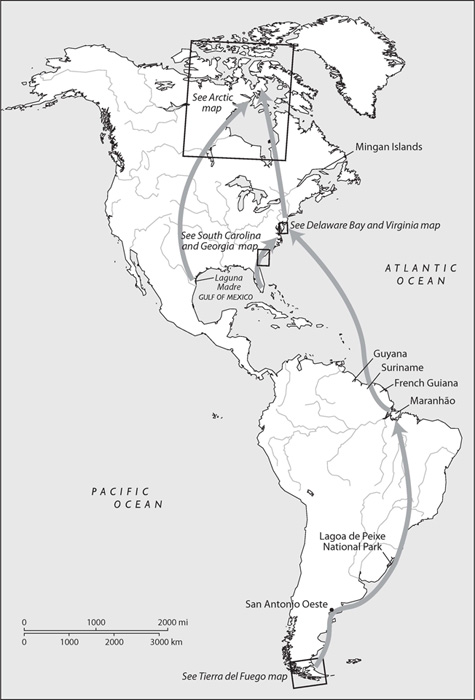

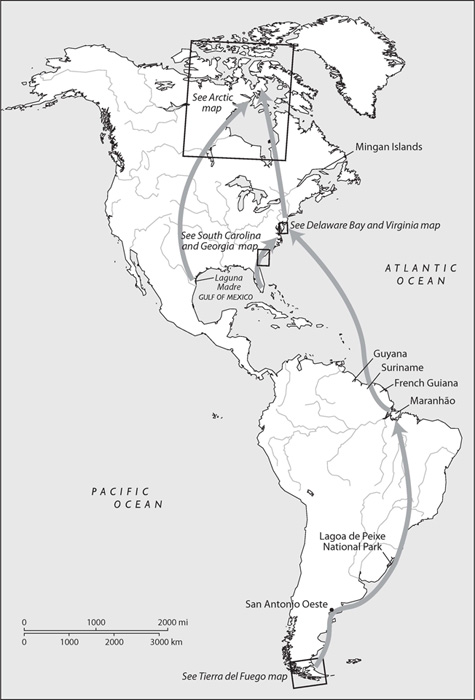

And that was only half their journey. Each year knots fly from one end of the Earth to the other and back. Consumed by curiosity, I followed them to learn what it takes to go such great distances, where they chose to stop along the way and why, and what was so special about those horseshoe crab eggs. This book is the story of that journey. I begin where many red knots live during the northern winter, a virtually inaccessible beach on the Strait of Magellan. When they begin flying north, I move with them, traveling to a crowded resort in Argentina, a saltwater lagoon in Texas, a hunting preserve in South Carolina. To see where knots build their nests in summer, I go to a lonely camp on Southampton Island in the Arctics Foxe Basin, home to large numbers of hungry polar bears. When the breeding season ends and knots begin their long return to South America, I see them off, from the boggy edge of Canadas James Bay, the foggy Mingan Islands, a low-lying Cape Cod beach whose nearby waters are increasingly visited by great white sharks, and finally, the bay behind my home.

The journey is not easy. I accompany dedicated biologists and birders, tracking birds by foot, walking 10 or 12 miles every day through ice and snow. We sit for hours in the pouring rain, counting shorebirds. We hide on windy beaches hoping to catch them in nets. The knots are elusive. Fueled on fat, warmed by feathers, they can go anywhere, no matter how remote. We fly, too, watching for them from helicopters; listening for them in a small propeller plane equipped with a radio receiver; and following them onto the tundra with the help of bush pilots for whom a narrow strip of icy gravel constitutes a runway. We travel by boat, train, komatik, SUV, and ATV, on rides that range from exhilarating to hair-raising. I learn to load and fire, reasonably accurately, a 12-gauge shotgun, and find to my surprise on the next stopover that I miss it.

Migration route of the red knot, Calidris canutus rufa (map by Bill Nelson; source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service).

The knots seem at home in hurricane winds that ground us and in bug-infested, alligator-ridden swamps. I live in a mosquito-filled marsh but on this trip am subjected to the worst concentrations of biting insects I have ever seen. The birds forage for all their meals. Eating tiny clams and horseshoe crab eggs, they double their weight before each major flight. I taste their food, supplementing it with wild game, gourmet meals, dried crackers, and peanut butterand lose weight. Slogging through isolated, remote areas looking for birds, I have a compass, GPS, and radio to keep track of myself. The birds havewhat? By the end of this journey I am more in awe than when I began.

The route isnt quite what I thought itd be. A few scraps of beach crowded with laughing gulls and shorebirds are a world-renowned hotspot for avian flu. One researcher there is funded by the Department of Homeland Security. In another state, I spend a morning not on a beach, but in a courtroom. Detouring off the well-marked path, I explore less recognized twists and turns that prove important, accompanying scientists as they uncover two previously unrecognized winter homes of young knots. Their work comes at a critical time. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has listed the red knot, Calidris canutus rufa, as threatened under the Endangered Species Act; it is likely to become in danger of extinction in the foreseeable future. Along the route, I see why. Horseshoe crabs, I learn, matter as much to our own well-being as they do to shorebirds. I follow horseshoe crabs to a gleaming oyster bank in South Carolina, to a biomedical company in Charleston, and then to Massachusetts General Hospital to find out how and why my life depends on an animal that comes ashore but once a year.

Next page