It is an amazing fact that in todays high-tech world we can solve almost any problem via the internet or with some staggeringly clever gadget, but sometimes you still cant beat a good, old fashioned knot! People have been tying knots to solve problems since the beginning of recorded history.

Using a piece of rope, cord, string or twine and securing it with a knot is often a simple, practical and very comforting way to solve many everyday problems.

The Pocket Guide to Essential Knots will show you how to tie 21 key knots for everyday use: for home, work, hobby and play activities, indoors and outdoors.

This small handy pocket book does not pretend to be a knot encyclopaedia, nor does it contain any knot-tying jargon or technical terms. It just contains easy to follow step-by-step tying instructions and possible uses for a handful of very useful and practical knots that should cope with most situations the average person will encounter.

Many people know how to tie one or two knots, not always correctly! This book is designed to give you a few more options. By helping you choose the right knot for the job and tie it correctly, this book hopefully will make life run just a little bit more smoothly.

It is possible to tie a knot with an extremely wide variety of materials, both natural fibres and man-made synthetics. Natural fibres such as cotton, flax, jute, sisal, coir, hemp, raffia and manila are still used but in general they have given way to man-made synthetic materials such as nylon, polyester, polypropylene and polyethylene.

The essential knots featured in this book are most commonly tied with rope, cord, string and twine. Ropes are traditionally anything over 0.5inch (12mm) in diameter and are often referred to as lines. Smaller stuff is known as cordage; while strings and twines are generally even thinner.

Nylon, first produced in 1938 for domestic use, was the first man-made, synthetic material to be used. Since then wide ranges of artificial rope, cord, string and twine have been developed to meet different purposes. Size for size they are lighter, stronger and cheaper than their natural counterparts. They do not rot or shrink and are resistant to most chemicals and common solvents. They can also be manufactured in long lengths and a wide range of colours and patterns. Despite all of the advantages that man-made synthetics bring with them, there is of course still a place for natural fibres. For example nearly all gardeners take a massive pride in their gardens and want to do things right, not only in a visual and practical way but also increasingly in an environmentally friendly way. A piece of natural biodegradable twine which is soft, pliable and gentle to plants can, when finished with, be composted down it never stops being useful!

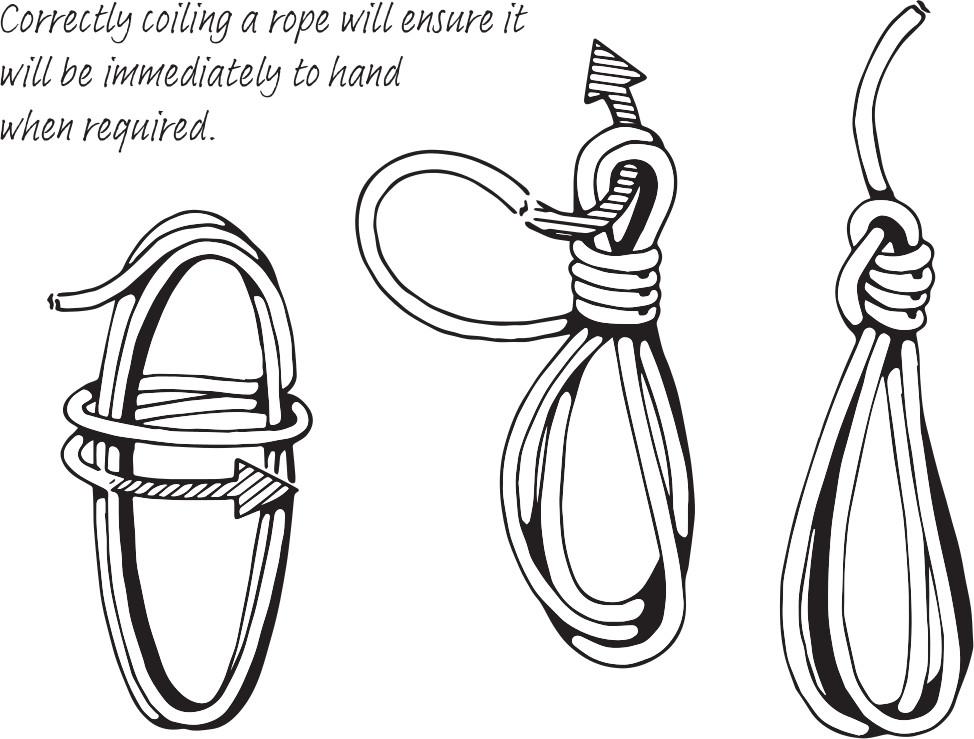

Man-made synthetic rope, cord, string and twine do have some disadvantages, the main one being they can melt when heated. In certain circumstances even the friction generated when one rope rubs against another may be enough to cause damage, so if you use artificial ropes in this situation it is vital to check them regularly. Rope, both natural and synthetic, can be expensive, so its worth looking after it properly. Always coil rope when not in use. If it is a natural fibre rope, always make sure it is dry before coiling and storing in dry conditions.

Rope is generally divided into two types, Laid and Braided.

Laid Rope

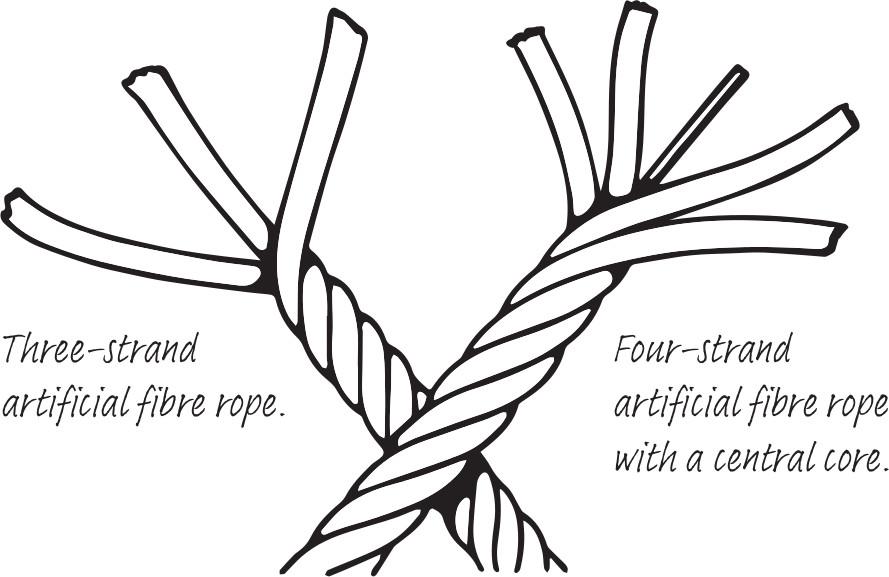

Artificial rope can be twisted or laid like old-style natural fibre rope. Usually three strands of artificial fibre are twisted together to form a length of rope; this process can also be the same for cord, string or twine. One very strong variation of three strands is four strands of artificial fibre twisted around a central core of artificial fibre.

The cost of laid rope is generally about two-thirds that of the more widely used braided rope (see page

Braided Rope

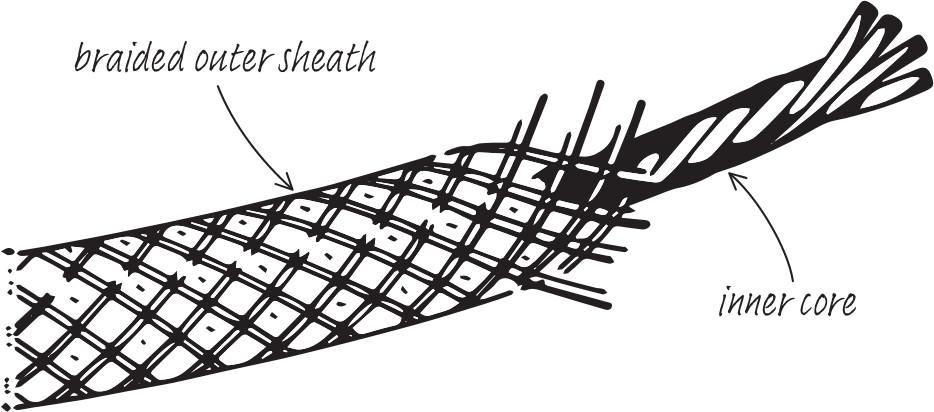

The combination of an outer sheath surrounding an inner core makes braided rope softer, more flexible, and generally a lot stronger than other types of synthetic rope.

The outer sheath generally consists of 16 braided strands. This surrounds an inner core that can be parallel fibres, or twisted, or plaited. Both the sheath and the core contribute to the strength and flexibility of the rope. Its flexibility makes it ideal for knot tying, while the smoothness of the outer sheath makes the rope easy and comfortable to handle.

It is very often thought that braided rope is only manufactured in larger diameter sizes, but modern production technology also enables this highly successful material to be manufactured in very small diameter sizes.

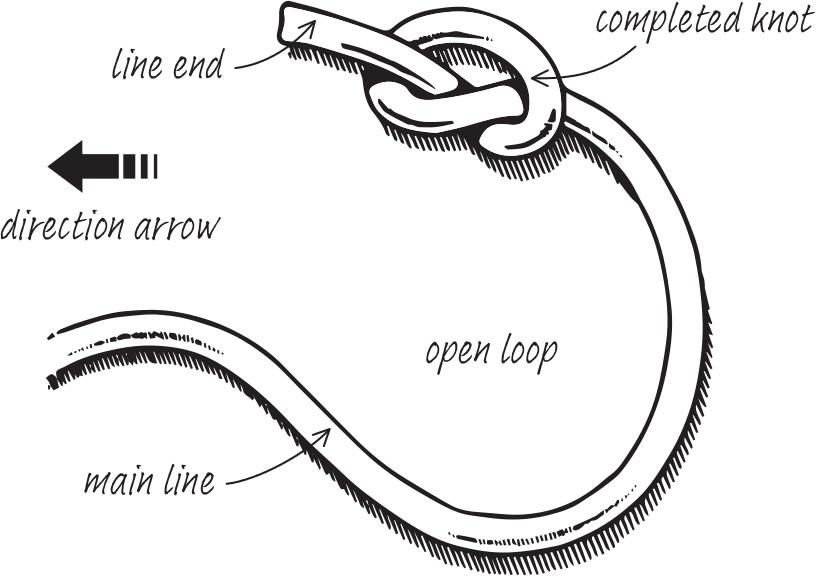

This book makes a conscious effort to avoid any knot-tying jargon or technical terms for example, the end of a line is simply called a line end.

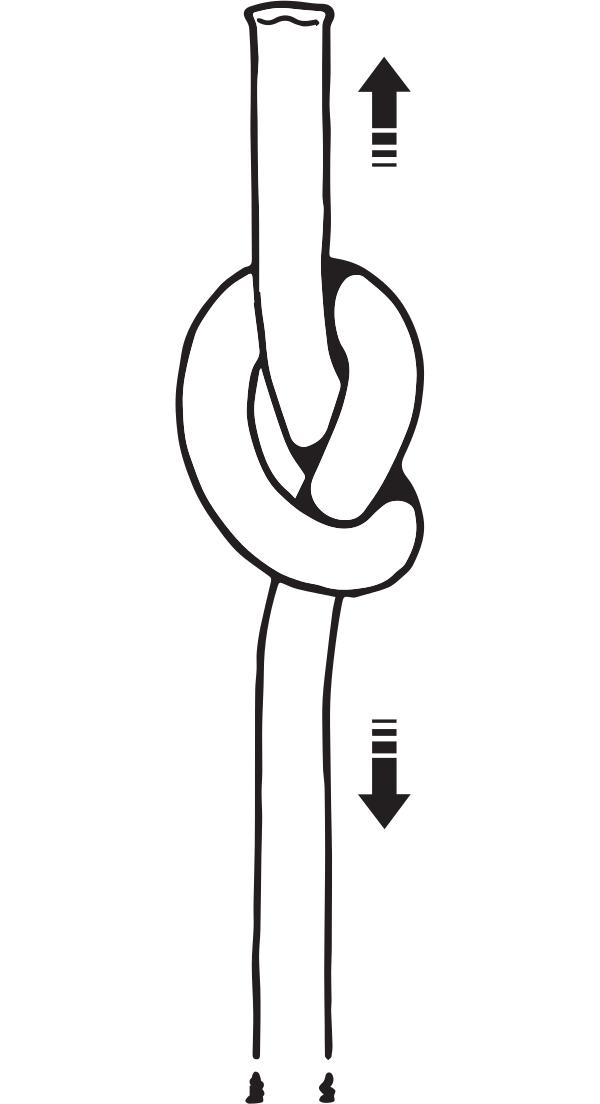

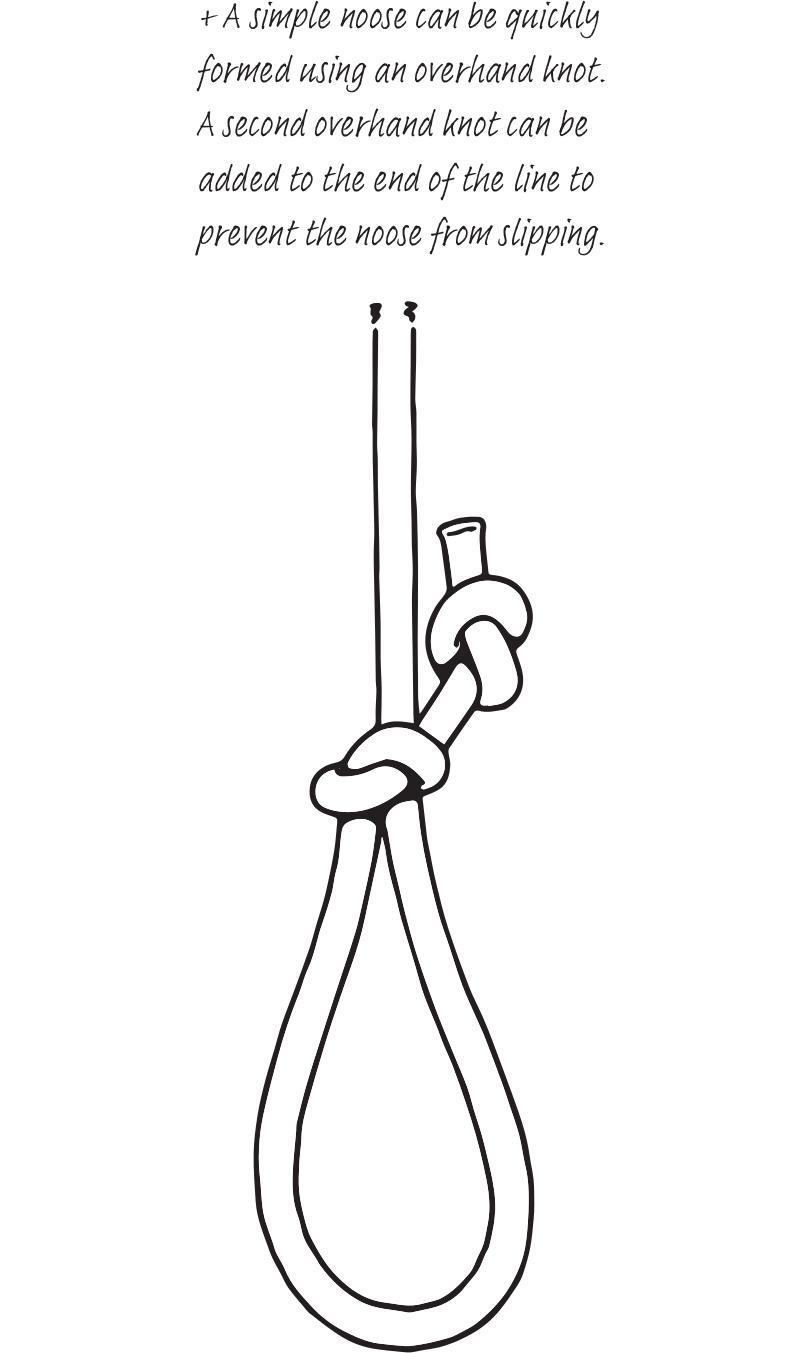

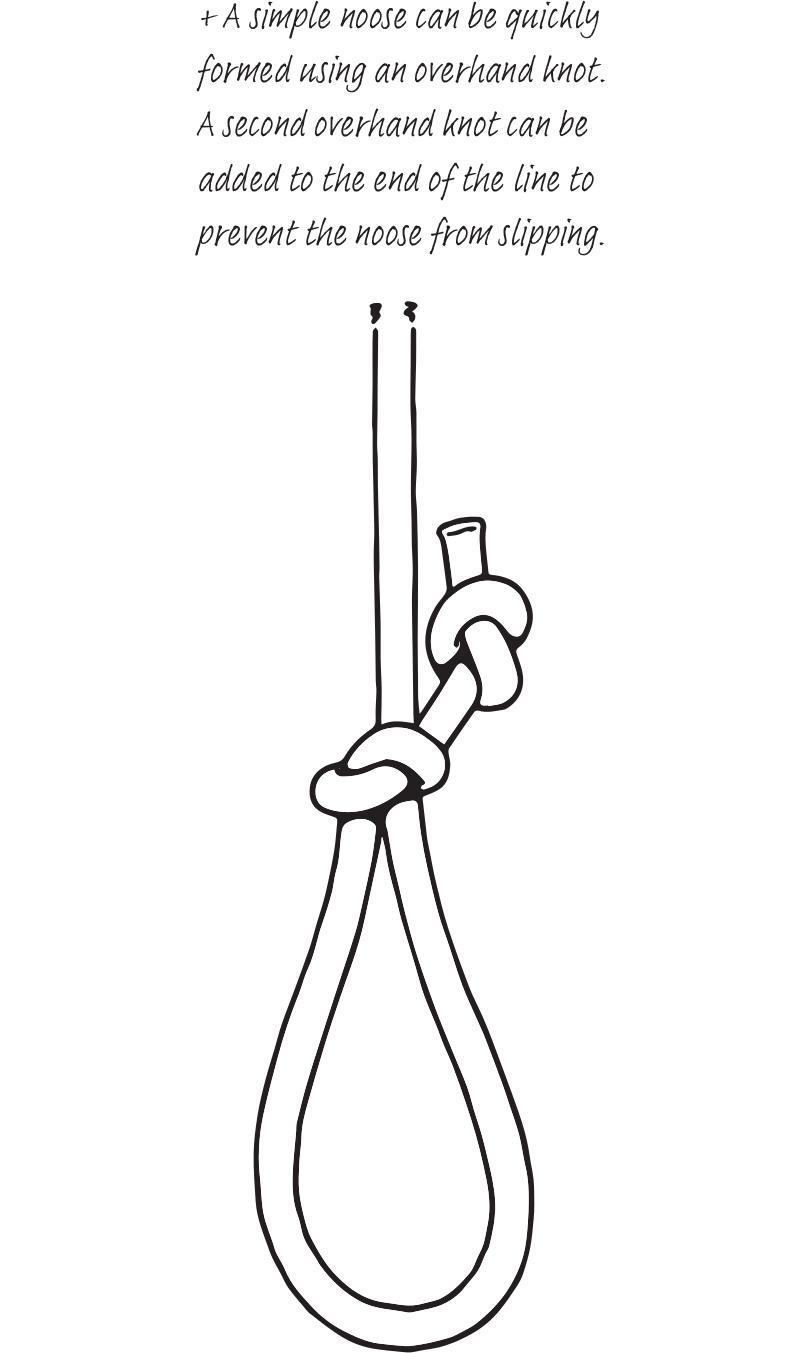

The illustrations accompanying the tying instructions are intended to be self-explanatory, but additional written instructions are included at specific points. Arrows show the directions to push or pull and dotted lines indicate intermediate positions. In many of the illustrations, lines are shown faded out or cut short for clarity, plus a certain amount of artistic licence has been used to enable the illustrations to fit into the available space. So always make sure you have sufficient line to complete the knot. This can often be calculated by looking at the illustration of the completed knot.

This is the best-known and most widely used of all knots. It is also the simplest knot to tie. It forms the basis of many other knots and is often used in conjunction with other knots. The most common use for this knot is as a stopper knot at the end of a piece of thread, string, cord or rope.

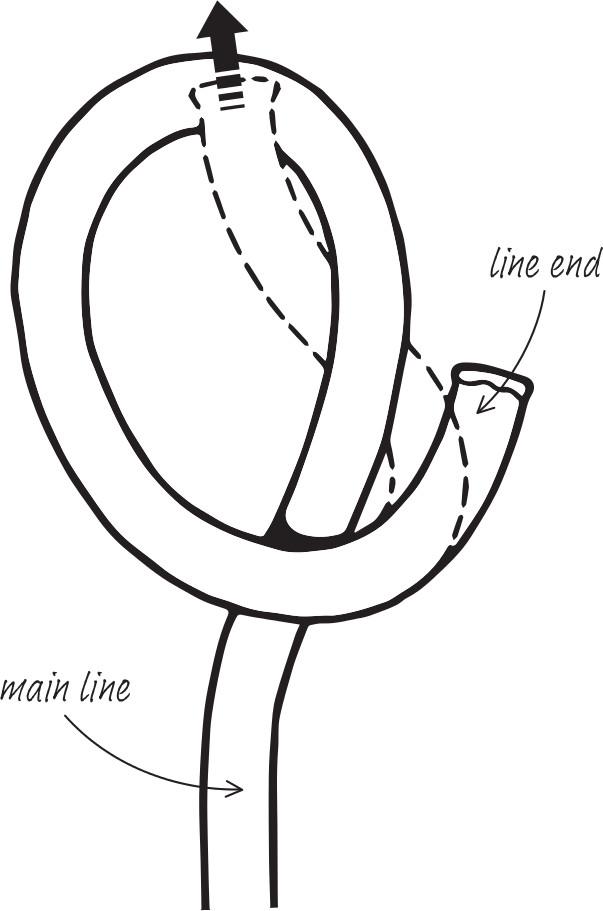

Double the line to form a loop and then bring the line end over the main line and under the loop. Then pull out through the loop in the direction of the arrow.

Double the line to form a loop and then bring the line end over the main line and under the loop. Then pull out through the loop in the direction of the arrow.

Position the knot where it is required and then tighten the completed knot by pulling in the direction of the arrows.

Position the knot where it is required and then tighten the completed knot by pulling in the direction of the arrows.

P OSSIBLE U SES?

Double the line to form a loop and then bring the line end over the main line and under the loop. Then pull out through the loop in the direction of the arrow.

Double the line to form a loop and then bring the line end over the main line and under the loop. Then pull out through the loop in the direction of the arrow.

Position the knot where it is required and then tighten the completed knot by pulling in the direction of the arrows.

Position the knot where it is required and then tighten the completed knot by pulling in the direction of the arrows.