NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2017 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moore, Lisa Jean, 1967 author.

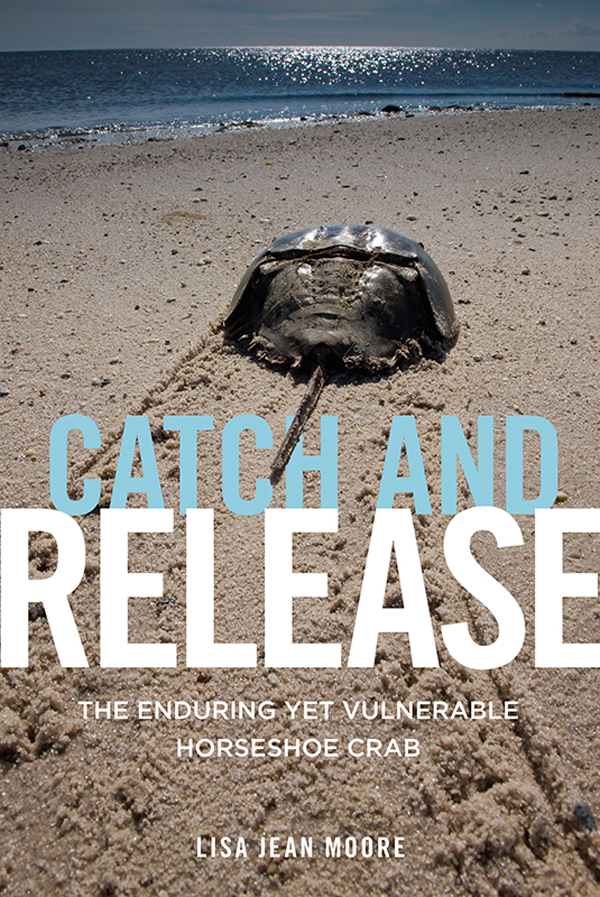

Title: Catch and release : the enduring yet vulnerable horseshoe crab / Lisa Jean Moore.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017010865 | ISBN 9781479876303 (cl : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781479848478 (pb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : Merostomata.

Classification: LCC QL 447.7 . M 66 2017 | DDC 595.4/9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010865

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

PREFACE

I get irritated by a certain type of academic voice. I react at times with both envy and incredulity at the ability to make sweeping declarations about large-scale interconnected phenomena spanning time, space, and economies. These statements resound with a manly, assured forcefulness of Truth, and I nod along in supportive feminine pantomime. I secretly think: How does he know that? and How can he say it so definitely? Everyone else seems to buy it, so I shrug and go along.

The contemporary cultural meme of how men explain things, or mansplaining, so diverges somewhat from my own reaction to this kind of academic voice. It is as if I hold out hope that I can do womansplaining, my own way of claiming a valued and respected voice, without having to be an annoying know-it-all. I want to be able to break out of the standard performance of scholar and be valued as a significant contributor, even if I am less declarative and more circumspect. And yet I certainly dont want my methodological rigor and status as a reliable narrator to be dismissed because I openly voice these internal dialogues. Instead of being seen as someone who produces knowledge in spite of this internal struggle, I want to deploy this struggle as an integral strength of my method and my scholarship.

Even as an undergraduate sociology student, I was drawn to symbolic interactionism, a theoretical and methodological perspective that examines the creation of social meaning. This sociological paradigm nourishes me at my intellectual core. I enjoy reveling in the creativity of meaning-making humans, learning and relearning the concept of the definition of the situation , and examining the unfolding human conflict inherent in wrestling with normative expectations. When making claims about my own research, Ive always been more comfortable keeping my analysis on the level of the microsociologicalsymbolic interactionisms bailiwick.

My brand of qualitative researchimmersion in a field site, long unstructured interviews with humans, learning new skill sets from indigenous knowledge producersserves as the basis for my interpretations about social life. So, for example, being on a blistering hot urban rooftop with a beekeeper as she carefully explains how to do a hive check becomes the basis for my grounded theories about the social world of urban beekeeping and its cultural significance. And watching a lab technician observing sperm through a microscope and using a hand tally counter, I can understand how sperm count comes to be pragmatically and discursively quantified as a measure of a man. As in all my empirical work, rarely do I stray too far from my data to make grand claims, relying instead on informants quotes for evidence of the claims I make. Deploying their words allows me to make larger observationsabout human reproduction, the spread of disease, the world, or the climateas a safeguard against my own grand theorizing or deploying my intellect.

When I signed the contract for this book, my lifeline and editor Ilene Kalish said, Well, we dont think this book will have a very large profile. Especially if you dont answer any questions, just raise them. Ouch. She referred to my previous books and my ambivalence in adding my voice to large-scale sweeping claims. Am I an academic wimp imprisoned by my femininity? Do I hedge my bets rather than stake my place as a knowledge producer? A dear friend encouraged me, after reviewing multiple drafts of my work, to liberate myself from my tendency to quote or genuflect textually to others. Why do I feel so uncertain about proving something, having a conclusion, or making a point? I do understand the critique, yet I cant manage to wholeheartedly embrace the epistemic authority of making definitive statements rather than raising important questions.

Perhaps I am a day late (2 decades?) and a dollar short in trying to amplify my voice as a knowledge producersomeone who makes definitive statements about FINDINGS . During my graduate school years in the 1990s, the swirling debates about human subjectivity and epistemology generated lively discussions of who has the permission to access and create knowledge. In particular, we examined what qualifies a scholar as legitimate, especially one from an othered position. We analyzed the feminist philosopher Nancy Hartsocks now oft-quoted lament about the plight of so many of us: Why is it that just at the moment when so many of us who have been silenced begin to demand the right to name ourselves, to act as subjects rather than objects of history, that just then the concept of subjecthood becomes problematic? We were attempting to come to terms with the opportunity to contribute to epistemology from our situated perspectives while simultaneously acknowledging that subjectivity itself was being dismantled.

As much as I want to join the club of those who can make larger pronouncements with the heft to back them up, to add to epistemology, there is always a tacit asking of permission, a split-second hesitation, or an implied qualification. The pleasures and dangers of reflexivity, adding the anecdotal reflection, can break up my inner tension. Instead of just saying something specific and firm, I opt to reveal some internal ambivalence couched in a humorous story. Writing from my own voice, grounded in my painstaking qualitative immersion, seems both self-indulgent and elusive in its legitimacy. This hand-wringing does feel particularly human, probably bourgeois, and most definitely femininesimilar to the ubiquitous apologizing of my sex. Perhaps this is what womansplaining looks like?

Thinking with Tenderness

While I am tentatively taking steps to move into, if not grand theorizing, at least less molecular theorizing, the clear waters of epistemological authority have been muddied by urgent calls to acknowledge our becoming with nonhuman animals. Ever so slowly, Ive grown to proffer contingent feminist epistemological and empirically grounded claims. But this is further complicated by my recent turn toward nonhuman animal ethnographymultispecies ethnography. No longer is it simply a matter of contributing to knowledgeif creating epistemology is level 1, the academic field is now at level 2: the re-emergence of, and reckoning with, ontology. The travails of knowledge production have in some ways become subordinated to matters of ontology. I believe it is only through these interactional, entangled, minute observations and speculations that I can begin to contribute to the literature on climate change, geologic time, conservation ecology, and biopharmaceutical industry. I do this through my examination and movement toward an engaged becoming with horseshoe crabs.