THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2011 by Richard Fortey

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House Inc., New York.

www.aaknopf.com

Originally published in Great Britain as Survivors by HarperPress, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, London, in 2011.

Knopf, Borzoi Books and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to Curtis Brown, Ltd.

for permission to reprint an excerpt from The Coelacanth from Selected Poems by Ogden Nash, copyright 1972 by Ogden Nash (London: Little, Brown & Co., 1972).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fortey, Richard A.

Horseshoe crabs and velvet worms : the story of the animals and plants that time has left behind / by Richard Fortey. 1st American ed.

p. cm.

Originally published as Survivors in Great Britain by HarperPress, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, London.

Includes index.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95741-2

1. ArthropodaConservation 2. InvertebratesConservation. 3. Limulus polyphemusConservation. 4. Worms. 5. Plant conservation. I. Title.

QL 434. F 67 2012

595dc23

2011039941

Cover image: Horseshoe crabs by Ernst Haeckel from Kunstformen der Natur (detail)

Cover design by Barbara de Wilde

v3.1

To my sister, with love

PROLOGUE

These anomalous forms may almost be called living fossils; they have endured to the present day, from having inhabited a conned area, and from having thus been exposed to less severe competition.

Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species

Evolution has not obliterated its tracks as more advanced animals and plants have appeared through geological time. There are, scattered over the globe, organisms and ecologies which still survive from earlier times. These speak to us of seminal events in the history of life. They range from humble algal mats to hardy musk oxen that linger on in the tundra as last vestiges of the Ice Age. The history of life can be approached through the fossil record; a narrative of forms that have vanished from the earth. But it can also be understood through its survivors, the animals and plants that time has left behind. My intention is to visit these organisms in the field, to take the reader on a journey to the exotic, or even everyday, places where they live. There will be landscapes to evoke, boulders to turn over, seas to paddle in. I shall describe the animals and plants in their natural habitats, and explain why they are important in understanding pivotal points in evolutionary history. So it will be a journey through time, as well as around the globe.

I have always thought of myself as a naturalist first, and a palaeontologist second, although I cannot deny that I have spent most of my life looking at thoroughly dead creatures. This book is something of a departure for me, with the focus switched to living organisms that help reveal the tree of life (see endpapers). I will frequently return to considering fossils to show how my chosen creatures root back into ancient times. I have also broken my usual rules of narrative. The logical place to start is at the beginning, which in this case would mean with the oldest and most primitive organisms. Or I could start with the present and work backwards, as in Richard Dawkins The Ancestors Tale. Instead, I have opted to start somewhere in the middle. This is not perversity on my part. It seemed appropriate to start my exploration in a place, biologically speaking, that is familiar to me. The ancient horseshoe crabs of Delaware Bay were somehow fitting, not least on account of their trilobite connections. Amid all the concern about climate change and extinction, it is encouraging to begin with an organism whose populations can still be counted in their millions. From this starting point somewhere inside the great and spreading tree of life I can climb upwards to higher twigs if I wish, or maybe even delve downwards to find the trunk. Let us begin to explore.

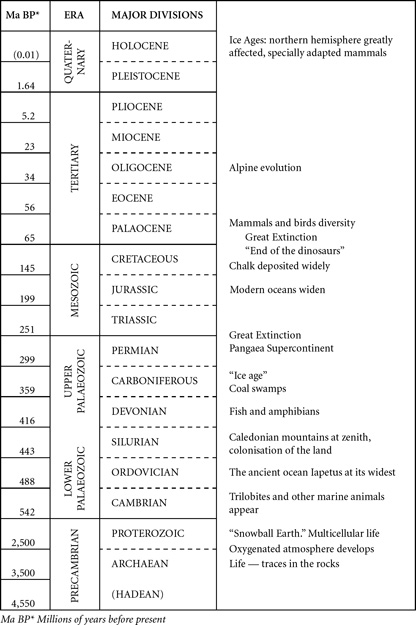

TABLE OF

GEOLOGICAL PERIODS

1

Old Horseshoes

Turn seawards off Route 1, Delaware, and a century rolls away. A small road soon leaves the commercial strip and the fast food joints behind, as it moves onto flat fields and marshland that still supports scattered, pretty villages lined with white-painted picket fences. This is how much of Americas east coast used to be. The Little Creek Inn is a grander building altogether: a large, foursquare, wooden Victorian farmstead on three floors with shutters at the windows and a fine portico, and inside all polished wood and turned banisters. In the spacious drawing room of the Inn, anticipation is buzzing. The hosts, Bob and Carol Thomas, are serving iced tea to a crew of enthusiasts all dedicated to travelling back much further in time than a mere century or so. This is the chance to come face to face with life as it was millions of years ago. Glenn Gauvry, the local expert, is waving around models of an ancient animal. A small TV crew is there to straighten out their facts before they get down to filming. Two young women biologists have travelled from Canada to see for themselves an event that only happens when the conditions are just right in late May. I am there with my notebook and a fluttering heart. All of us are impatient for darkness to fall.

Deep in the night along the shores of Delaware Bay, the horseshoe crabs are stirring. The tide is now high and there is no moon. Darkness rules, but even in the feeble starlight the overwhelming flatness of the countryside can be made out, except along the rim of the bay where old sand dunes have built up a levee providing foundations for a scattering of wooden beach houses, which loom against the night sky. A path passes between them onto a sandy beach that stretches away into the darkness in a long gentle arc. The shoreline seems to heave with gentle movements.

First, I notice some very odd sounds. There is a general hollow clattering, a tapping and grinding sound, somewhat like that made by knocking coconut shells together (once used on the radio to imitate horses hooves) but altogether less rhythmic, and with a kind of underlying push. Then, as my eyes get used to the darkness, low shelly mounds the size of inverted colanders can be seen slowly pushing and jostling all along the shore and perhaps six metres up onto the sands. Their bumping and clambering together is the source of those tap-tapping percussive sounds. The flash of an infrared torch reveals more details. The head-shield of the horseshoe crab is domed upwards and carries a few weak spines; at its back end a hinge marks a jointed boundary with a second large plate, spiny at the edge, which can flap downwards; and beyond that again projects a stout triangular spike as long as the head, which can waggle up and down. Here at Kitts Hummock more crabs are gathered on the mud flats seaward of the sands waiting their turn: strange, green-black, slowly animated lumps. Further offshore again in the shallow sea-water, tail spikes project briefly above the gentle waves like raised radio antennae and are gone, showing where still more horseshoe crabs vie with one another to get their place on the sand. There are evidently thousands upon thousands of these large animals gathered together in some sort of compulsive collusion.