William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright Richard Fortey 2016

The author asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

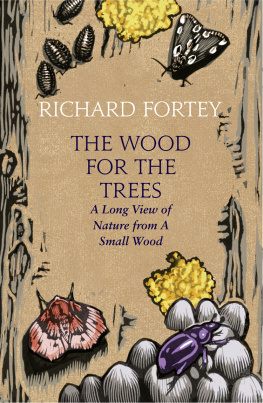

Cover illustration Chris Wormell

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008104665

Ebook Edition May 2016 ISBN: 9780008104672

Version: 2016-03-16

For Eileen and Stuart Skeates

Contents

1

After a working life spent in a great museum, the time had come for me to escape into the open air. I spent years handling fossils of extinct animals; now, the inner naturalist needed to touch living animals and plants. My wife Jackie discovered the advertisement: a small piece of the Chiltern Hills up for sale. The proceeds from a television series proved exactly enough to purchase four acres of ancient beech-and-bluebell woodland, buried deeply inside a greater stretch of stately trees. The briefest of visits clinched the deal exploring the wood simply felt like coming home. On 4 July 2011 Grims Dyke Wood became ours.

I began to keep a diary to record wildlife, and the look and feel of the woodland as it passed through diverse moods and changing seasons. I sat on one particular stump to make observations, which I wrote down in a small, leather-bound notebook. I was unconsciously compiling a biography of the wood bio in the most exact sense, since animals and plants formed an important part of it. Before long, I saw that the story was as much about human history as it was about nature. For all its ancient lineage, the wood was shaped by human hand. I needed to explore the development of the English countryside, all the way from the Iron Age to the recent exploitation of woodland for beech furniture or tent pegs. I was moved by a compulsion to understand half-forgotten crafts and revive half-remembered words like bodger, spile and bavin. Plans were made to fell timber, to follow the journey from tree to furniture; to visit the canopy in a cherry-picker; to explore the archaeology of that ancient feature, Grims Dyke, that ran along one side of the plot. I wanted to see if the wood could yield food as well as inspiration.

My scientific soul reawakened as I sought to comprehend the ways that plants and animals collaborate to generate a rich ecology. I had to sample everything: mosses, lichens, grasses, insects, and fungi. I investigated the natural history of beech, oak, ash, yew, and all the other trees. I spent moonlit evenings trapping moths; daytime frolicking with nets to catch crane flies or lifting up rotten logs to understand decay. I poked and prodded and snuffled under brambles. I wanted to turn the appropriate bits of geology into tiles and glass. The wood became a route to understanding how the landscape is forever in a state of transition, for all that we think it unchanging. In short, the wood became a project.

Grims Dyke Wood is just a segment in the middle of more extensive ancient woodland, Lambridge Wood, lying in the southern part of the county of Oxfordshire. Splitting Lambridge into separate plots generated a profit for the previous owner, but also allowed people of modest means to own and care for their own small piece of living history. Our fellow woodies as Jackie terms them proved to include a well-known harpsichordist, a retired professor of business systems, a founder member of Genesis (the band, not the book), a virologist turned plant illustrator, ex-actors turned psychologists, and a woman of mystery. Our own patch is one of the smaller ones. All of the woodies have their own reasons for wanting to be among the trees some desire simply to dream, some would rather like to turn a profit, others to explore sustainable resources. I believe I am the only naturalist. All the owners are there to prevent the wood from being felled or turned into housing. For the long history of Lambridge Wood tells us that our trees are less worked today than at any time in the past. This sad redundancy is no less part of its tale, as our wood is inevitably connected to the wider world of commerce and markets. The histories of my home town, Henley-on-Thames, a mile away, and the famous river on which it sits, are bound into the narrative of the surrounding countryside. Ancient manors controlled the fate of woodlands for centuries. I have to imagine what the wood would have seen or heard as great events passed it by; who might have lurked under the trees, what poachers and vagabonds, poets or highwaymen.

Once the project was under way a curious thing happened. I wanted to make a collection. This may not sound particularly remarkable, but for somebody who had worked for decades with rank after rank of curated collections it was rejuvenation. Life among the stacks in the Natural History Museum in London had stifled my acquisitiveness, but now something was rekindled. I wanted to collect objects from the wood, not in the systematic way of a scientist, but with something of the random joy of a young boy. Perhaps I wanted to become that boy once again. Eighteenth-century gentlemen were wont to have cabinets of curiosities in which they displayed items that might have conversational or antiquarian interest. I wanted to have my own cabinet of curiosity. I would add items when my curiosity was piqued month by month: maybe a stone, a feather, or a dried plant nothing for the eighteenth-century gent. I believe that curiosity is a most important human instinct. Curiosity is the enemy of certainty, and certainty particularly conviction that other people are different, or sinful, or irreligious lies behind much of the conflict and genocide that disfigure human history. If I could issue one injunction to humankind it would be: Be curious! My collection will be a way of encapsulating the whole Grims Dyke Wood project: my New Curiosity Shop. And I already know that the last item to be curated will be the leather-bound notebook.

The collection requires a cabinet to house it. Jackie and I plan to fell one of our cherry trees and convert it into a wonderful receptacle for the woods serendipitous treasures. We must discuss the work with Philip Koomen, a noted Chiltern furniture-maker devoted to using local materials. Philips workshop, Wheelers Barn, is in the remotest part of the Chiltern Hills, only about five miles from Grims Dyke Wood as the crow flies, but about fifteen as the ancient roads wind hither and thither. His studio is imbued with calm. Polished sections through trees hanging on the walls show the qualities of each variety: colour, texture, grain, and age all combine to distinguish not just different tree species, but individual personalities. No two trees are identical. Some have burrs that section into turbulent swirls. Pale ash contrasts with rich walnut, and cherry with its warm tones is satisfactorily different from oak. This is a man who cares deeply about materials and believes in the genius loci an integration of human and natural history that lends authenticity to a hand-made item. Philips handiwork from our own cherry tree will be a physical embodiment of our wood, but by housing the idiosyncratic collection picked up as the project develops it will also