Acknowledgements

It would have been impossible to write this book had I not been awarded the Collier Chair in the Public Understanding of Science and Technology at the University of Bristol for 2002. I am most grateful to the Institute of Advanced Studies, University of Bristol, and particularly Professor Bernard Silverman, for granting me time, and a quiet attic, to escape the hassles of my normal life. Karine Taylor, secretary to the Institute, was helpful in countless small ways which made my stay in Bristol a pleasure. I thank Paul Henderson of The Natural History Museum in London for facilitating my sabbatical leave at Bristol.

While researching the book I was compelled to explore parts of the geological column that are not my usual habitat, and to extend my expertise into new fields. I profited enormously from the generosity of several geologists who guided me over territory well-known to them, but novel to me. Geoff Milnes, and his daughter Ellen, were charming guides around the eastern Alps, and patiently tolerated my naive questions. Graham Park took me around the Northwest Highlands at a time of the year when most sensible people (even Scottish people) are sat round the fire with a hot toddy. Geoff and Graham also revised the appropriate parts of my manuscript, and corrected mistakes and misapprehensions. I need hardly add that any infelicities or inaccuracies that remain are entirely the responsibility of the writer. Several years ago, Dr. Ajit Varkar of Pune arranged my trip to the Deccan traps in northwestern India, negotiating with drivers and guides alike. I could not have completed this excursion without his help. Paul and Jodi Moore provided unstinting hospitality in Hawaii for me and my family, and were the best possible company in the tropical evenings (I hope they got the sand out of the carpet). I cannot thank them enough. Sam Gon helped me understand aspects of Hawaiian culture. Several colleagues generously gave me advice in return for no more than a free lunch. I may still owe one or two. I particularly thank Claudio Vita-Finzi and David Price of University College, London, for advice on the Bay of Naples, and the middle of the earth, respectively. Bernard Wood of the University of Bristol spent an afternoon showing me how rock samples can be crushed so hard as to change their character, which was invaluable for my chapter Deep Things. I also thank John Dewey, Tony Harris, David Gee, Bob Symes, Joe Cann, and my old Newfoundland friends for advice of one kind or another. Adrian Rushton and Derek Siveter provided moral support in the pub at times of crisis.

I am particularly indebted to Robin Cocks, John Cope and Heather Godwin, who read through the first version of the book, and made several suggestions for its improvement. Heather has always had a crucial role in my writing career, as an infallible arbiter of taste, and excisor of bad jokes. Arabella Pike at HarperCollins has proved again an enthusiastic and supportive editor, and her organisational skills ensured that the whole work came together.

I sincerely thank my wife, Jackie, for once again tolerating the writer at work, and, more specifically, for organising several of the field trips which comprise the core of the book. Jackie and my daughter, Rebecca, did much of the picture research for the colour plates.

Robert Francis provided me with many excellent photographs, which greatly enhanced the attractiveness of my natural history of the earth. I thank Ray Burrows for his skillful drawings. James Secord, Ted Nield, John Cope, David Gee, John Moorby, Jerry Ortner, Graham Park, and Geoff Milnes also provided illustrations, for which I am much indebted.

Preface

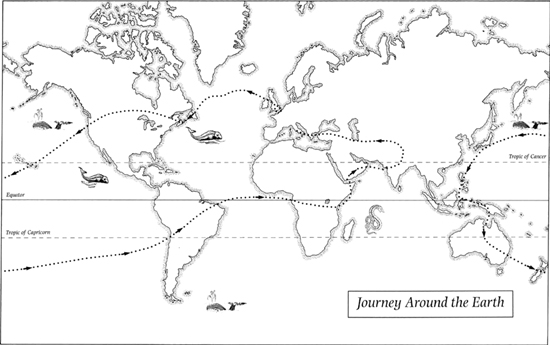

For some years I have been thinking about how best to describe the way in which plate tectonics has changed our perception of the earth. The world is so vast and so various that it is evidently impossible to encompass it all within one book. Yet geology underlies everything: it founds the landscape, dictates the agriculture, determines the character of villages. Geology acts as a kind of collective unconscious for the world, a deep control beneath the oceans and continents. For the general reader, the most compelling part of geological enlightenment is discovering what geology does, how it interacts with natural history, or the story of our own culture. Most of us engage with the landscape at this intimate level. Many scientists, by contrast, are propelled by the search for the inclusive model, a general theory that will change the perception of the workings of the world. In most scientific papers, the intimacies of plants or places are hardly given a second glance. Plate tectonics has transformed the way we understand the landscape, for the world alters at the bidding of the plates, but much of the transformation has been expressed in the cool prose of the scientific treatise. The problem is how we can marry these two contrasting modes of perceptionthe intelligent naturalists sensitive view of the details of the land with the geologists abstract models of its genesis and transformation. My solution has been to visit particular places, to explore their natural and human history in an intimate way, thence to move to the deeper motor of the earthto show how the lie of the land responds to a deeper beat, a slow and fundamental pulse. I have chosen my examples with some care, for they are all places that have figured in unscrambling this complex and richly patterned planet of ours. I have visited them all, so that the reader will also have this particular guides reactions to the sights, sounds, smells, and ambience of the critical localities. At the same time, I have endeavoured to show how knowledge of the deeper tectonic reality has changed over the last century or so. Great minds have pondered the shape of the world, and have purveyed theories of everything that have come and gone. Many past theories have been founded on good reasoning for their time and place, and it would be a complacent scientist today who would claim that present knowledge is as far as it goes. Understanding advances by building upon, and criticising the work of those who went before. It is a messy and complicated business, in which the human heart has as much a part to play as human intellect. This, too, is an ingredient in my story. The most difficult decisions I faced were not what to include, but what to leave out. I am acutely aware that there are areas of science that are merely sketched herein, any one of which would merit a book of its own. Geo-chemical cycles and their role in earth systems are a case in point. The intercedence of extraterrestrial events in our history is another fascinating field in which many recent advances have been made. The omission of such things in the interest of a coherent narrative was a painful necessity. What my story lacks in omniscience I hope it makes up for in coherence and accessibility.