Olivier Martini s sketches, paintings, and prints have been displayed at the Marion McGrath Gallery and Studio Three Gallery, published in Alberta Views magazine, and were included as part of the Canadian Mental Healths Copernicus Project. His first book, Bitter Medicine: A Graphic Memoir of Mental Illness, a collaboration with his brother Clem, won the City of Calgary W.O. Mitchell Book Prize.

Clem Martini is an award-winning playwright, screenwriter and novelist. He has over thirty plays and ten books of fiction and non-fiction to his credit, including the popular young adult trilogy The Crow Chronicles. His texts on playwriting, The Blunt Playwright, The Greek Playwright, and The Ancient Comedians, are used in universities and colleges across the country. He teaches in the department of drama at the University of Calgary.

THE UNRAVELLING

THE UNRAVELLING

Clem Martini & Olivier Martini

How our caregiving safety net cameunstrung and we were left grasping atthreads, struggling to plait a new one

If I had a world of my own, everything would be nonsense. Nothing would be what it is, because everything would be what it isnt. And contrary wise, what is, it wouldnt be. And what it wouldnt be, it would. You see?

LEWIS CARROLL

To deal with mental illnesses and dementia is to enter a mirror world, where words can often mean their opposite. Truth and lies can be exchanged, one for the other, and perhaps the most dangerous lies are the ones we tell ourselves.

Introduction

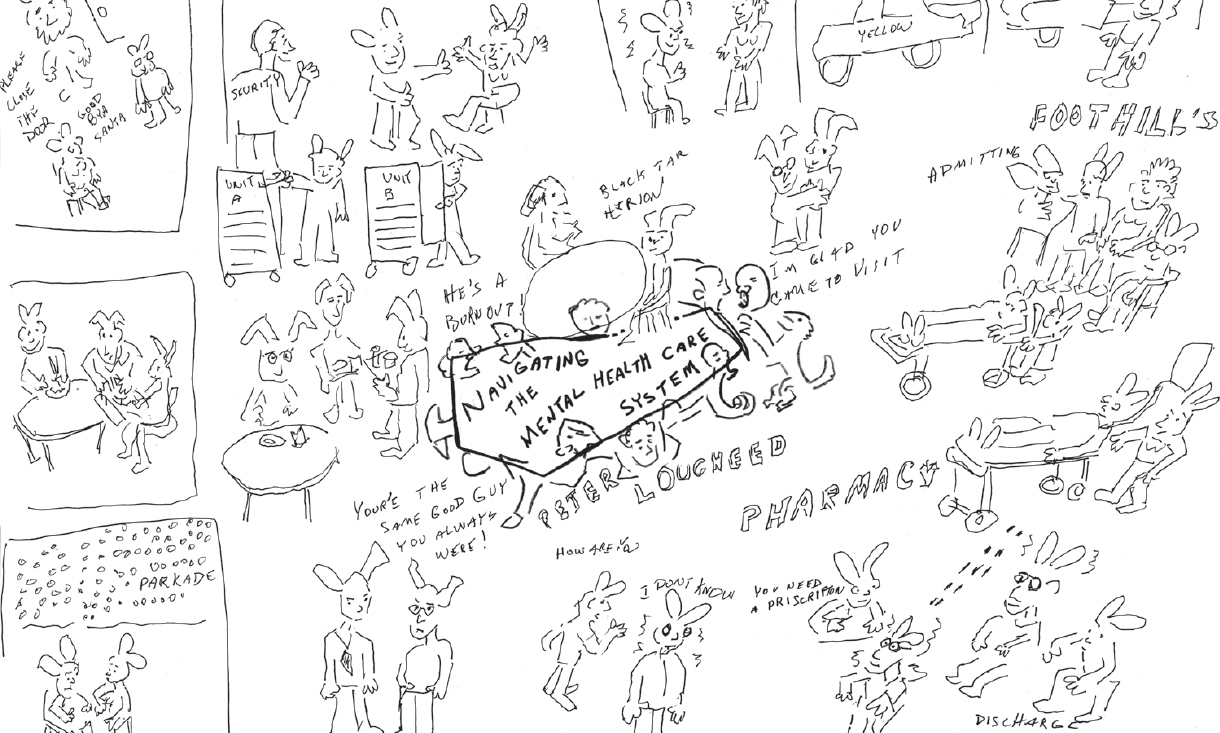

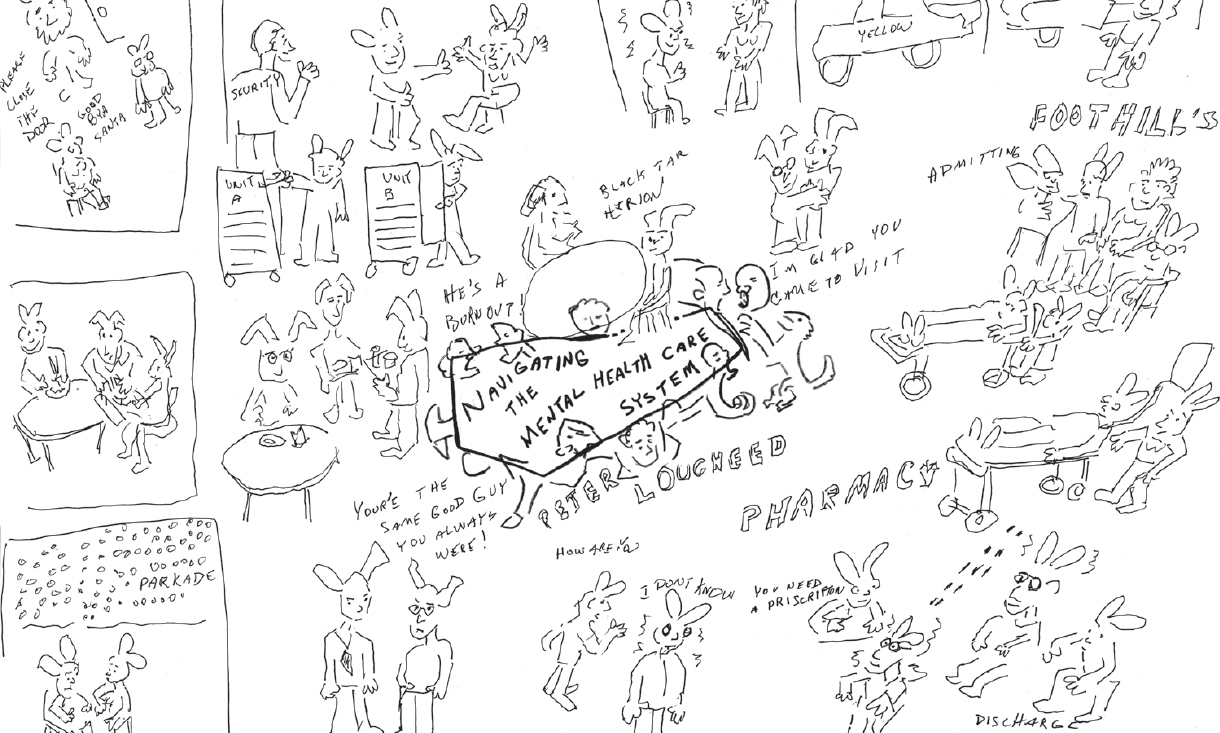

The Unravelling is the story of Liv and his family. Liv has schizophrenia. His mother, his caregiver of many years, is sinking into the abyss of dementia. His brothers, who provide ongoing support, pick up the pieces whenever the health care system fails. Who or what is unravelling in this story? Liv? His mother? His brothers? The system?

Caregiving can be complicated. In some cases the line between caregiver and recipient can be blurry. For years Livs mother cared for him, and in return Liv provided emotional support, companionship, and physical help to her. What happens when the delicate balance is interrupted by the onset of ill health, old age, dementia, and the once reliable caregiver becomes care recipient? Other family members intensify their engagement, now caring for a brother with schizophrenia as well as a mother with several physical health issues and escalating dementia. Clem, Livs brother and the narrator of this story, seems to sail through the murky waters of schizophrenia and dementia care with much poise. He is an experienced caregiver and knows how to navigate the system, but his endurance is tested times and again. Dementia, as Clem notes, isnt a decline: its a plummet from a precipice. And as you fall you strike against the rocky cliff face, each strike removing another portion of who you were. For Liv, the pain of losing his mother his main support to dementia, is compounded by the feeling that he has failed to take care of her.

With most of us, if not all, expected to be caregivers or care recipients at one time or another, and with the current state of health care throughout the country, the picture is bleak. This book is a testimony to the trials and tribulations of one family, whose patience and good will are exhausted by an unfriendly, often hostile health care system; it is also a manifesto against the priorities that create the many shortcomings of health and social services.

This very personal and intimate book is extraordinary in its description of ordinary situations. Accompanied by Livs moving drawings, which are at once filled with compassion, confusion, fear, and at times humour, it is a must read for us all.

Ella Amir, Executive Director, AMI-Qubec Action on Mental Ilness

Ella Amir has been working with families affected by mental illness since 1990 in her capacity as the Executive Director of the Montreal-based AMI-Quebec Action on Mental Illness. Ella was the chair of the former Family Caregivers Advisory Committee at the Mental Health Commission of Canada and is now a member of its Advisory Committee.

Its early and dark when the phone rings.

I havent had breakfast yet and am just set up at the dining room table, papers strewn in front of me, picking at my computer keyboard and nursing a cup of warm tea. I lift the receiver, cradle it to my ear, and am surprised to hear my brothers psychiatrist on the other end. Dr. Baxter apologizes for calling early, tells me she has phoned Oliviers, and has been unable to reach him. Where is he?

His blood work has returned from the lab, she tells me, and theres a problem. The tests indicate his white blood cells have been seriously compromised. She mentions the possible condition he is suffering from its long and scary-sounding: agranulocytosis. Its essential that he get to emergency at once, she says.

I consider where he might be. Olivier is an early riser, and each morning he promptly flies out the door. Typically, his day is crammed full of visits to support groups, social agencies, and art clinics. I recall he had mentioned that he would be working on a sculpture in his art class at Self Help, a community mental health support centre.

I say Ill try to get hold of him there. She tells me shell call the Foothills Hospital to prepare a placement for him.

The coordinator at Self Help says Olivier has just arrived so I ask her to bring him to the phone. When he picks up, I fill him in on the situation and tell him that Ill drive down and get him. The coordinator, who has overheard the conversation, interrupts to say shell call a taxi to save time.

Liv and I meet at the hospital twenty minutes later. I steel myself to accompany him through emergency intake, which I tend to view as something like hell with all the good bits left out. There are the endless lineups: first you line up to receive an identification number and state your condition, then you line up again to see someone who will establish if the condition is serious, then you wait for someone to arrive who will actually examine you, and so on. There are the sad, angry, tortured souls haunting the waiting room, the feverish and the drunk, the bleeding and the nauseous. There are the chairs, designed to punish, and over everything hangs the smell of vomit blended with the sharp, piney odour of disinfectant.

So, now we wait.

An hour and a half later were transferred into the examination area and a doctor arrives. He confirms what Livs psychiatrist suspected: Oliviers white blood cell count has plummeted. The doctor is young and self-assured and not particularly adept at communicating. I ask a few questions. No, he doesnt know why this condition has suddenly appeared. No, he doesnt know what can be done. No, there are no beds available. It will be several hours before Liv can expect a placement, and I reflect that emergency, where every form of virus, germ, or bacteria collects, is the worst possible environment for someone with a compromised immune system.

Next page