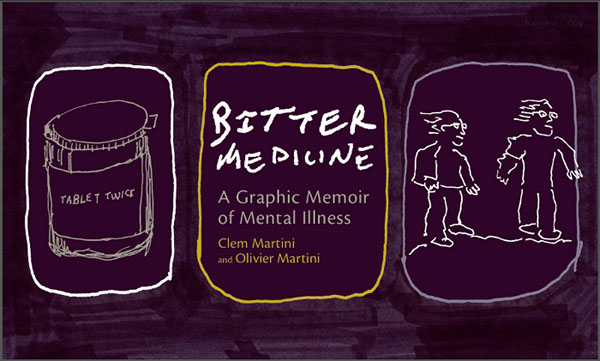

Bitter Medicine

A Graphic Memoir of Mental Illness

Clem Martini and Olivier Martini

Copyright 2010

Clem Martini and Olivier Martini

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanicalincluding photocopying, recording, taping, or through the use of information storage and retrieval systemswithout prior written permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, ON, Canada, M5E 1E5.

Freehand Books gratefully acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for its publishing program. Freehand Books gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publishing program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

Edited by Melanie Little

Cover and interior design by Natalie Olsen,

www.kisscutdesign.com

Freehand Books

515, 1st Street SW

Calgary, Alberta T2P 1N3

www.freehand-books.com

Book orders:

UTP Distribution

5201 Dufferin Street Toronto, Ontario M3H 5T8

Telephone: 1-800-565-9523

Fax: 1-800-221-9985

utpdistribution.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Martin, Clem, 1956

Bitter medicine: a graphic memoir of mental illness / Clem Martini and Olivier Martini

Includes bibliographic references.

ISBN 978-1-55111-928-1 (print)

ISBN 978-1-4604-0015-9 (epub)

1. Martini, BenMental health.

2. Martini, OlivierMental health.

3. SchizophrenicsFamily relationships.

4. Mental health servicesAlberta.

5. SchizophrenicsCanadaBiography.

I. Martini, Olivier

II. Title.

RC514.M359 2010 616.89'800922 C2009-907035-9

To our family: immediate, extended, alive, and dead.

And to all those who live and struggle with mental illness.

Foreword

Bitter Medicine: A Graphic Memoir of Mental Illness graphically and artistically captures the fears and frustrations that all too often accompany the devastation caused by schizophrenia for those living with the illness and their family members. Clem and Olivier Martini make one of the strongest and most compelling cases that I have ever encountered as to how we as a society have failed those with mental illness.

The last major transformation of the mental health system was deinstitutionalization during the 1960s and 1970s; as Clem and Olivier illustrate, it was a colossal failure. Mental health services remain underfunded, and there is little social or political will to redress that imbalance. As the Martini family knows so well, this affects countless individuals and their families who must live with second-rate, third-rate, or no psychiatric care at all. Furthermore, the stigma attached to mental illness and the resulting social exclusion prevents many of those affected from even seeking treatment in the first place.

However, it is within our power to change the current situation. We have learned a lot from those living with severe mental illness about what helps and hinders them in regaining their quality of life, and it is widely accepted that recovery-oriented mental health services can address the failures of deinstitutionalization. These services aim to facilitate active self-management of psychiatric disorders, as well as the reclamation and maintenance of a positive sense of self, roles, and life beyond the mental health system based upon hope, personal empowerment, respect, self-determination, and connection with community supports and services. One in one hundred people will experience some form of schizophrenia. Our hope is that, with increased awareness and expanded professional and community support systems, most will learn to live beyond the limitations of schizophrenia. But they cannot do it alone.

From an experiential, ethical, and social justice perspective, Bitter Medicines clarion call is that we can and must do a much better job as a society in addressing the needs of those living with mental illness. Canada is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, with a pool of knowledge about the various services and supports that can successfully treat mental illness. To choose not to provide or fund the necessary mental health services becomes a social injustice issue.

Bitter Medicine is not just the story of a personal journey, but of one of the greatest social justice issues of our time.

Chris Summerville is the CEO of the Schizophrenia Society of Canada, the executive director of the Manitoba Schizophrenia Society, and a board member of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, established in 2007. With his own personal experiences of mental illness, he is also a family member.

Introduction

A lot has been written about mental illness from a clinical perspective, but very little attempts to truly understand the experience from within and across a family. In Bitter Medicine, my brother Olivier and I have tried to do that: to generate some kind of understanding by tossing questions back and forth and chewing them over, me with words, my brother with drawings. Its been more than three decades since our younger brother was first diagnosed. I imagine weve spent the better part of those past thirty years, each in our own manner, reviewing and chewing.

Many of the remembrances raised and discussed in this process were awkward, painful, and private, things we often would have preferred to avoid or ignore. I hope that in writing and drawing our way through this, weve managed to capture some element of the truth.

A parallel world exists beyond the one we normally operate in. This is the story of how my family entered that other dimension and has never been able to fully return.

Clem Martini and Olivier Martini

Calgary, Alberta, July 2009

Part One

The biggest thing to understand is that we were nothing remarkable.

We were four skinny boys with bad haircuts growing up in a tiny grey house perched near the foothills. The town we lived in was small and, in the summer months, laden with dust. There were only gravel roads then, and one lonely street lamp down at the end of the corner that flickered and writhed when thunderstorms swept through. Bowness hadnt yet been swallowed and digested by our neighbouring community, Calgary. It still required two buses and a transfer if you wanted to perform any kind of serious shopping.

We owned a restless black spaniel, a fat, white short-haired rabbit, and a cat that was grey as a puff of smoke. (A little poetic perhaps, but thats the way I thought of her. Everyone smoked back then, so I suppose it was only natural.) We didnt have much money, so during the hot, dry summers we camped down in the badlands and hiked to pass the time. We took turns climbing among the sun-baked hills with the dog. We searched for the glossy, serrated dinosaur teeth that could be found glittering among the clay and cacti and the massive, rusty stumps of petrified wood.

Next page