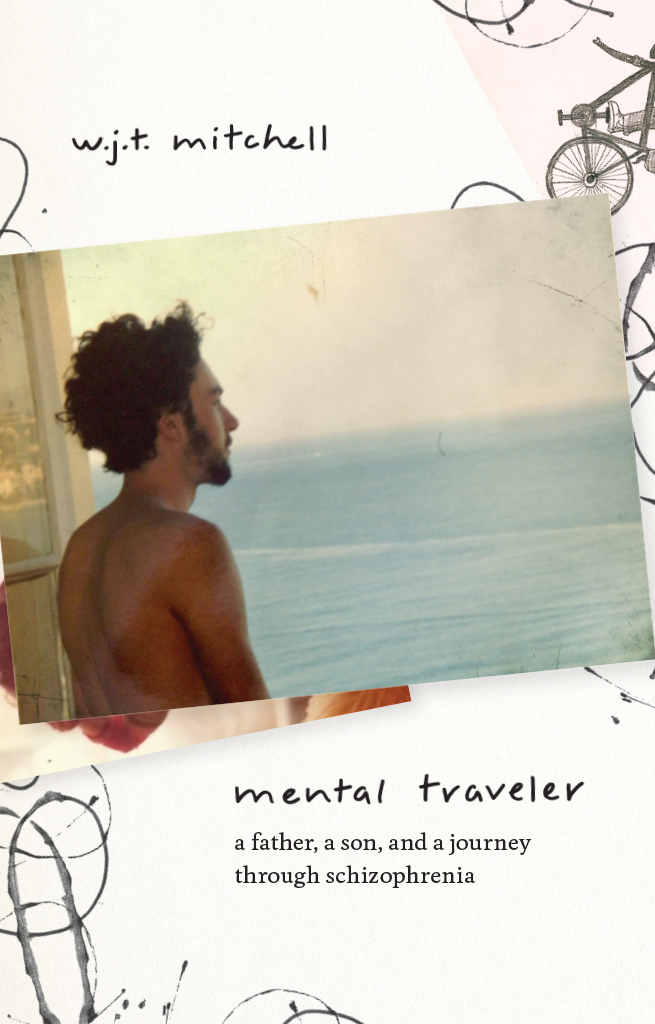

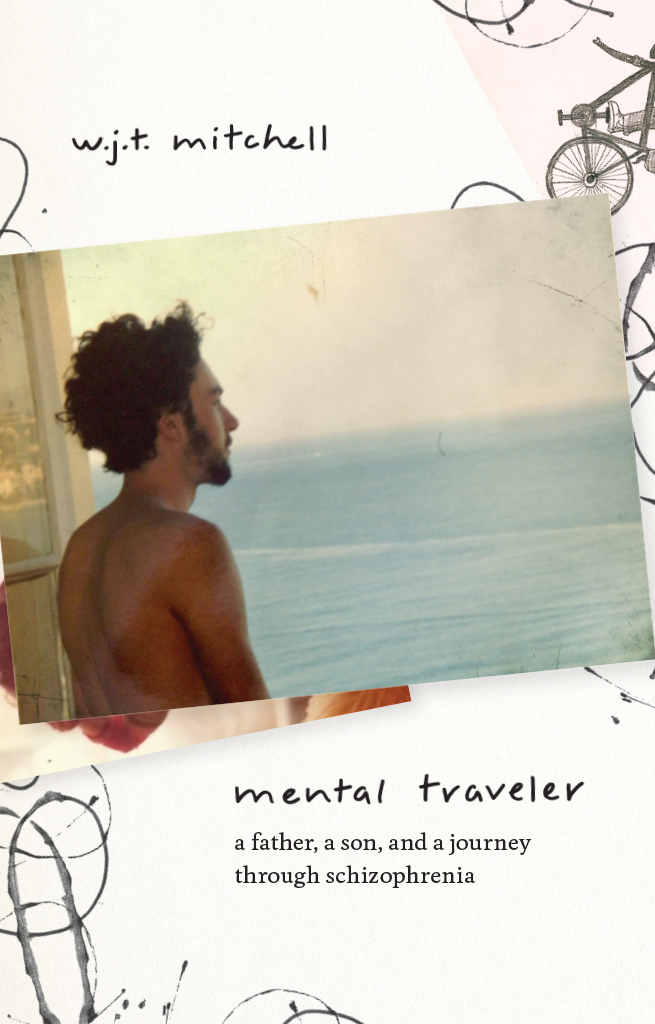

A Father, a Son, and a Journey through Schizophrenia

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2020 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2020

Printed in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-69593-8 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-69609-6 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226696096.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mitchell, W. J. T. (William John Thomas), 1942 author. | Misurell-Mitchell, Janice.

Title: Mental traveler : a father, a son, and a journey through schizophrenia / W. J. T. Mitchell.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019052214 | ISBN 9780226695938 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226696096 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mitchell, Gabriel, 1973-2012. | Mitchell, Gabriel, 19732012Mental health. | Mitchell, W. J. T. (William John Thomas), 1942 Family. | SchizophrenicsIllinoisChicagoBiography. | ArtistsIllinoisChicagoBiography. | Motion picture producers and directorsIllinoisChicagoBiography. | Mentally illFamily relationships. | Fathers and sons. | Art and mental illness. | Mental illness in motion pictures. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC RC514 .M526 2020 | DDC 616.89/80092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052214

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

I travelled through a land of men

A land of men and women too

And heard and saw such dreadful things

As cold earth wanderers never knew.

WILLIAM BLAKE, The Mental Traveller

CONTENTS

There are two kinds of books: the ones you want to write, and the ones you have to write. I have written quite a few of the first kind, but this is not one of them. It is a memoir of the life and death of my son, Gabriel Mitchell, who struggled with schizophrenia for twenty years until his suicide at age thirty-eight. It is not a book I wanted to write, or ever expected that I would write, until the fatal day of June 24, 2012.

In many ways, Gabe was a typical case of schizophrenia. First onset of symptomsdepression, anger, delusions, hallucinationsaround age nineteen. Dropping out of college and into the mental health system, hospitalization, medications, therapies, halfway houses. A decade spent battling addiction to alcohol and drugs, and enduring the stigma that comes with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Part-time employment as a grocery clerk. An early death at thirty-eight, probably triggered by overwork and the stress of passing for healthy and normal. End of story.

But as anyone who has lived with mental illness knows, typical cases are also deeply singular and individual. Everyone goes crazy in their own way, and every family has its own way of dealing with their disturbed son or daughter, brother or sister, father or mother. Every derangement is a response to an arrangement, a de-arrangement of social and institutional circumstances. Although mental illness often results in isolation from family and society, it never happens alone. Some families are shattered; some become stronger. Some victims surrender and disappear into their symptoms, living out their days in quiet suffering. Others fight back with every means at their disposal. This is the story of someone who fought back and attempted to see his own madness with complete lucidity, and to see through it to something beyond. It is also the story of a family that helped him survive schizophrenia for twenty years and is now determined that his life will endure beyond his suicide. As Gabe once put it, People are always changing. Even beyond the grave, they are changing.

I have tried to see through Gabes madness, to see beyond the medical labels and stereotypes and apprehend the concrete individual who himself attempted to look back at madness from the inside with art and work and skill. Of course, I think my son was very special, and I know that I share this view with every parent who has lost a child. But specialness is both typical and specific, ordinary and singular. My aim here is to specify and commemorate the unrepeatable life of my son, to tell the story of his struggle and to make you see him clearly right up to the moment of his departure and beyond. If this story helps others who are blessed with a beloved mental traveler, so much the better.

To call someone a schizophrenic, as if it named an identity rather than an illness, is without question politically incorrect. Better to say a person with schizophrenia, or (following R. D. Laing) a so-called schizophrenic. Laings formulation has the advantage of recognizing that schizophrenia, like diabetes, is an illness that becomes an identitywhat society calls you whether you like it or not. It is not a chosen identity but is imposed from outside, most fatefully by medical authorities. For oneself, the choice is between saying I have schizophrenia, or I am a schizophrenic. Gabe was comfortable saying either, choosing the identity label when he was feeling militantly political about affirming schizophrenia as a minority position. I have tried not to fuss over these distinctions very much in these pages. When I apply the word schizophrenic to a person, you should read it as silently adding so-called to recognize that it is a label applied from without, rarely from within.

I Need to Become Homeless

In the fall of 1991 I received an urgent phone message from Gabe, just a few weeks after he enrolled as a freshman at NYU . He had something important to tell me, and I must call back immediately. What could it be? Some insight into his choice of a major? Has he met the girl of his dreams? All our phone conversations to that point had been filled with enthusiasm. He loved his classes, especially philosophy. All my teachers love me, especially Dr. F, who thinks Im brilliant. The student parties and the caf scene of Greenwich Village were beyond cool. I flashed back to my own experiences as a college freshman in 1960, on my own for the first time, discovering sex and existentialism. Although we had thought a small rural liberal arts college might have been a better place for Gabe, he was enthralled with the idea of New York. And indeed, it seemed the perfect place for his boundless curiosity and offbeat sensibilities. Gabe had always been a seeker, and it was not unusual for him to announce a new passion that would mark a turning point in his life.

When I made the call, he got right to the point. Dad, I have discovered the authentic way of life. Its obvious to me that I have to give up everything and become homeless. Well, thats really interesting, I said, warily putting on my college counselor hat. Im sure that NYU has great programs in social work that would be just the thing if you want to work with the homeless. No, Dad. I dont want to

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).