A dog starvd at his masters gate

Predicts the ruin of the state.

WILLIAM BLAKE,

Auguries of Innocence (1803)

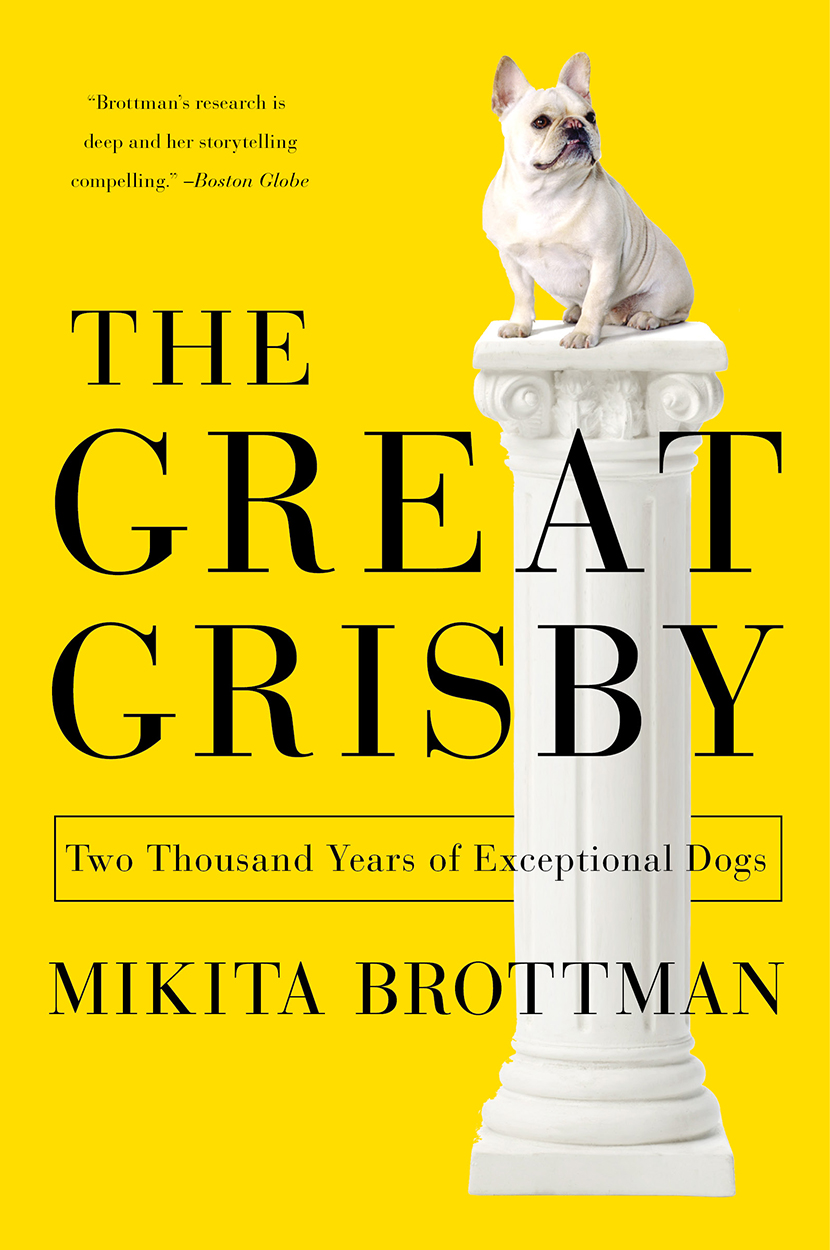

UNABLE TO LOVE each other, writes the British author J. R. Ackerley, the English turn naturally to dogs. I acquired my first dog when I was close to forty, and my eight-year love affair with this willful and charismatic animal has led me to wonder whether its true, as Ackerley suggests, that theres something repressed and neurotic about those whose deepest feelings are for their dogs. Thinking about this question has led me not to an answer but to further questions. Is my relationship with Grisby nourishing or dysfunctional, commonplace or unique? Do we choose and train dogs in our own image? Why are some people drawn to poodles, some to bulldogs, and others to dachshunds? Can devotion to a dog become pathological? Why is a womans love for her lapdogs considered embarrassingly sentimental when men bond so proudly with their well-built hounds? Married women admit they sleep with their dogs, and married men deny it; someones not telling the truth, but whos lying, and why? What drives some people to wash their hands obsessively after any canine contact while others are happy to share flatware with Fido? And why is Fido still used as the generic dogs name when its been out of fashion for almost a hundred years?

Each of this books twenty-six chapters is devoted to a particular human-canine bond. Some of these couplings are drawn from literature, where dogs are generally symbolic, often standing as their owners avatars, sharing similar characteristics or drawing attention to vital clues that the human characters have overlooked. Other pairings are drawn from history, art, folklore, and philosophy, and cover a broad span of history (320 BC to the 1970s) and geography (Rome, Russia, Japan, Germany, Mexico, Malta, Greece, the United States), but particular attention is paid to dog-and-owner pairs from Victorian Britain. According to authorities on the subject, late-nineteenth-century England saw the origins of modern dog breeding and pet keeping, which led to an increase in the depiction of dogs in art and literature, as well as their increase in everyday life, among all classes and age groups.

Far apart as these human-dog stories may be in time and place, their themes are remarkably consistent. Exceptional dogs, it turns out, often have traits in common, and the most familiar of these is miraculous loyalty. History and folklore are full of dogs that wont leave their owners dead or injured bodies; dogs that spend every night at their masters graves; dogs that drown themselves in grief, conceal themselves under their mistresses skirts as theyre led to the scaffold, or travel thousands of miles to make their way home. The fact that such tales have become folklore does not mean they are not also true. Dogs are remarkably faithful creatures. Upon further investigation, however, these miraculously loyal dogs often turn out to be rather less miraculous than their stories suggest, though no less interesting for that.

Many of the dogs described in this book will be unfamiliar to the reader, and Im especially interested in these lesser-known dogs. A lot has been said and written already about iconic, mediagenic dogs like Lassie, Old Yeller, and Rin Tin Tin. In The Great Grisby, I draw attention to dogs that inhabit the margins or lurk on the periphery, dogs that have been overlooked. As is so often the case, those who are allowed behind the scenes or on the sidelines (children, servants, janitors, busboys) often get to see and experience things that are normally kept from public view. Partly because they cant speak but mainly because they dont judge, dogs have unfettered access to the backstage of life. Imagine what Prince Alberts dog Eos could have told us about Queen Victoria, or what Freuds dog Yofi might have learned from his masters patients. A dog in the room is a silent observer, a witness to the human drama: it sees all, smells all, and says nothing.

All the dogs described in this book are, like Grisby, exceptional. This obviously raises the question of what makes an exceptional dog. The answer is simple. What makes a dog exceptional is its owner. In other words, any dog can be exceptional if its loved enough. We see our dogs through human eyes; this is the transformative power of projection. In order to understand this process more fully, I don my psychoanalytic hat and, taking a cue from Freud (another late-life dog lover), I put the human-canine relationship on the couch (never mind the dog hair). The way we think about our dogs is infinitely revealing. Rich insights can be gained from observing how people name their dogs, create personalities for them, address them, speak on their behalf, even from the way they pick up after them. For some, a dog is an alter ego; for others, a substitute for a child; other people use their dogs to keep the world at bay, to heal wounds inflicted in infancy, or to recapture their playful, preverbal selves.

The Great Grisby is structured like a leisurely stroll in the park. We begin with Atma, the name given by the misanthropic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer to his succession of standard poodles, and continue alphabetically until we arrive at Zmire, the adored pet of the French poet and intellectual Madame Antoinette Deshoulires. However, the path is not always direct. In this book, as on all our walks, Grisby sometimes leads us on sidetracks, following scents, sniffing out clues and connections, retracing our steps, taking us into the realms of folklore, semiotics, philosophy, and zoology. Sometimes he seems to be leading us astray, but as long as were together, well never be lost. Everywhere, every day, he shows me how dog is the mirror of man.

Contents

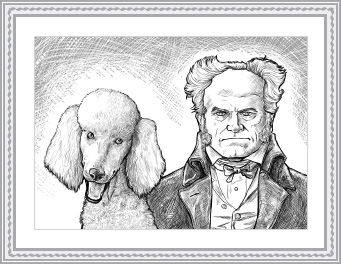

THE FAMOUSLY MISANTHROPIC German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer spent twenty-seven years of his life living alone, averse to human company, but like other notorious malcontents, he was deeply attached to his dogs. Throughout his life, from his student days at Gttingen until his death at Frankfurt am Main, Schopenhauer owned a succession of standard poodlesa famously loyal, active, and intelligent breed. To anyone who needs lively entertainment for the purpose of banishing the dreariness of solitude, he wrote in 1851, I recommend a dog, in whose moral and intellectual qualities he will almost always experience delight and satisfaction.

Though he remained loyal to the standard poodle, the philosophers companions varied in color. The dog he owned in the 1840s was white, and the one he owned at his deathand for which he provided generously in his willwas brown. According to the few guests who visited his home, Schopenhauer was deeply attentive to these animals; though his daily routine was rigid, he always made sure his poodles got regular constitutionals. He even concerned himself with their daily amusements. One colleague recalled being in the middle of an earnest conversation with the philosopher at his home when they were interrupted by the music of a regimental band passing the window, at which point Schopenhauer got up and moved his poodles seat closer, to give him a better view of the procession.

The philosopher was ahead of his time in his concern for animal suffering. When I see how man misuses the dog, his best friend; how he ties up this intelligent animal with a chain, he wrote, I feel the deepest sympathy with the brute and burning indignation against its master. Yet curiously, while he respected his dogs as individuals, Schopenhauer gave every one of them the same name: Atma (though his last dogthe brown onegenerally went by the nickname Butz).