To my mother,

Madeline Finch,

who has waited much too long for it

All men dream, but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dreams with open eyes, to make it possible.

T.E. Lawrence

Seven Pillars of Wisdom

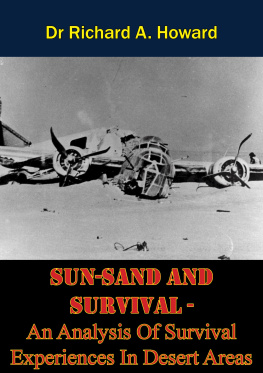

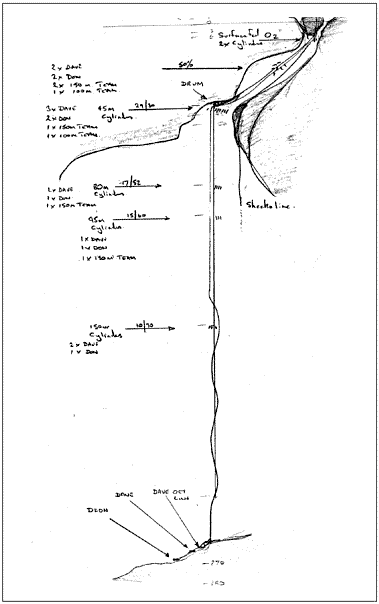

Diagram of Bushmans Hole by Don Shirley (May 2007) showing position of shot lines and placement of emergency cylinders and gas mixtures at each level. Drawn to scale.

On an afternoon in November 2004, David Shaw climbed a steep path up a mountainside that rose above Clearwater Bay in the New Territories of Hong Kong. His pacehard, unflinching, non-stopwas typical of Shaw, a driven man who did everything with a purpose.

Shaw was fifty years old, a training captain with Cathay Pacific airline who helped to oversee the flight fitness of other Cathay pilots while flying the lines long-haul routes. He and his wife, Ann, both Australian, had recently celebrated their thirtieth wedding anniversary. With their two children at universities in Australia, the Shaws lived alone in the home that they owned, overlooking Clearwater Bay. They were prosperous, stable, settled: apparently typical of their circle of acquaintances in Hong Kongs English-speaking expatriate community.

Recently, however, those people had begun to understand that Dave Shaw was not like anyone they had ever known.

In October, he had gone on a diving trip to South Africa. In the past five years, after he learned to scuba dive during a family holiday in the Philippines, Shaw often flew around the world to dive, taking advantage of an airline pilots flight benefits. Shaws acquaintances imagined him at beach resorts, spending languid days on bright ocean reefs, swimming with tropical fish.

Harry (a pseudonym), one of Shaws close friends in Hong Kong and director of a large Hong Kong business, had first met Shaw fifteen years earlier, when the Shaws had moved to Hong Kong and joined a small Christian congregation that included Harry and his family. He admired Shaws intelligence and quiet confidence. Shaw spoke little, bragged not at all and accomplished much.

Shortly after Shaw returned from South Africa, Harry asked him whether he had enjoyed the trip. Shaws answer was curious.

I did, he said. I went quite deep.

Shaw referred Harry to a website address. As soon as Harry returned home, he opened the web page.

Welcome to deepcave.com, a website created by Dave Shaw, the opening page read. Written in the third person, the text described how Shaw had quickly moved from recreational scuba to more challenging, and more risky, pursuits:

Dave was introduced to diving by his son and immediately knew that technical diving was his area of interest. Following some penetration wreck dives in the Philippines, Dave decided cave diving was worth exploring. Once completing the cave course in Florida, it has only really been cave diving that has been of interest since

He is primarily interested in exploring. To be where no other man has explored before is the ultimate in his opinion. It seems that to achieve that goal, greater depths are becoming a must.

Another page on the site linked to reports of Shaws notable dives. To anyone with any knowledge of diving, the dives were beyond extraordinary. They bordered on the unreal.

In October 2003 he accomplished two dives past 180 metres at Komati Springs, South Africa, including a critical equipment failure and what Shaw described as a near-death experience.

In June 2004 he dived to 213 metres in one of the worlds deepest underwater caves: BoesmansgatBushmans Hole in South Africa.

During the trip just completed, Shaw had become the third diver in history to return from the bottom of Bushmans. His depth of 270 metres was a world record for the diving apparatus known as a rebreather.

During that dive, as he swam along the bottom, Shaw found the body of a young man who had disappeared ten years earlier while diving in the hole. Shaw had briefly tried to lift the body with the thought of bringing it to the surface, but he had become over-exerted. With his allotted time on the bottom running out, he was forced to leave the corpse behind.

His online dive report described the incident:

I was headed for what appeared to be a deeper section of the cave and was laying line as I swam. This was cave diving at its best. I scanned the floor as I went, taking in the scenery. It appeared the cave would not go much deeper. I sweeped right and left with my HID light as I moved forward

I was relaxed and could almost not believe where I was. I was slowly descending and reached a depth of 270m I swept left with my HID light, at an angle of about 30 degrees, and 15 m away I saw a body, as plain as day. This had to be the body of Deon Dreyer, who died on the 17th Dec 1994. Even following extensive searches his body had never been found.

He was lying on his back, arms in the air and legs outstretched. There was no shock on my part, but rather a decision-making process of what to do. Do I continue for depth or go to the body? The decision was easy really. I turned and was soon next to him. I needed to try and make a recovery of the body.

Time was critical. I was within seconds of my turn time and I needed to make a decision. I tried to lift him, but to no avail. I knelt next to him and tried harder. I was now puffing and panting with the exertion. This was not wise I told myself. I am at 270m and working too hard Time to go; I was one minute over my maximum bottom time already. I tied off my reel to him so that he could be found again, not even wasting time cutting the reel free. I followed my line back to the shot line and started my ascent.

Nearly all recreational diving takes places at depths above 40 metres. Many divers never exceed 30 metres. With his dive in October, Shaw had become the fifth sports diver in history to exceed 700 feet (213 metres) and survive; more men have walked on the moon. In five years of part-time diving, he had gone from rank beginner to one of the worlds most accomplished and ambitious divers.

And he had done it without ever mentioning his feats to anyone in Hong Kong. Even Ann had had only a vague idea that he was going far beyond the norm.

Now, as Shaw crested the ridge at the end of his long climb, he encountered Harry, who had taken a more leisurely path to the top. The two men stood chatting for a few minutes, taking in the spectacular view of the bay.

Harry remarked on Shaws strenuous push up the hill. Shaw explained that he was trying to stay fit for his next big dive. He said that he would be returning to South Africa soon, back to the bottom of Bushmans Hole.

Harry was surprised and dismayed. He was not a diver, but he knew that cave diving was among the worlds most hazardous sports, and he guessed that Shaws extreme cave diving must be unimaginably dangerous and challenging.

He knew, for sure, that Shaw had much to lose, a truly enviable life with a devoted wife, good health, all the money that he would need.

Whats the point? Harry said. Youve already done that.

Not like this, Shaw said. Nobody has ever done anything like this. Im going back to get the body.

* * *

Bushmans Hole is about 500 kilometres southwest of Johannesburg, between the towns of Kuruman and Danielskuil, in the Northern Cape province of South Africa. It lies within the 34,000-acre Mount Carmel Game Farm, in the semi-arid green Kalahari, a region of scrub brush, sere grass and a rolling, rocky terrain.