Contents

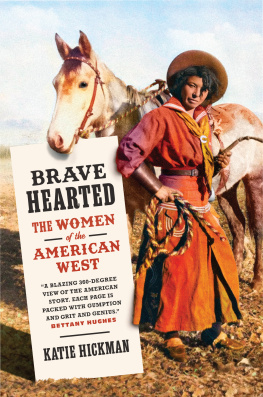

Brave Hearted

SPIEGEL & GRAU

Copyright 2022 by Katie Hickman

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Spiegel & Grau, New York

www.spiegelandgrau.com

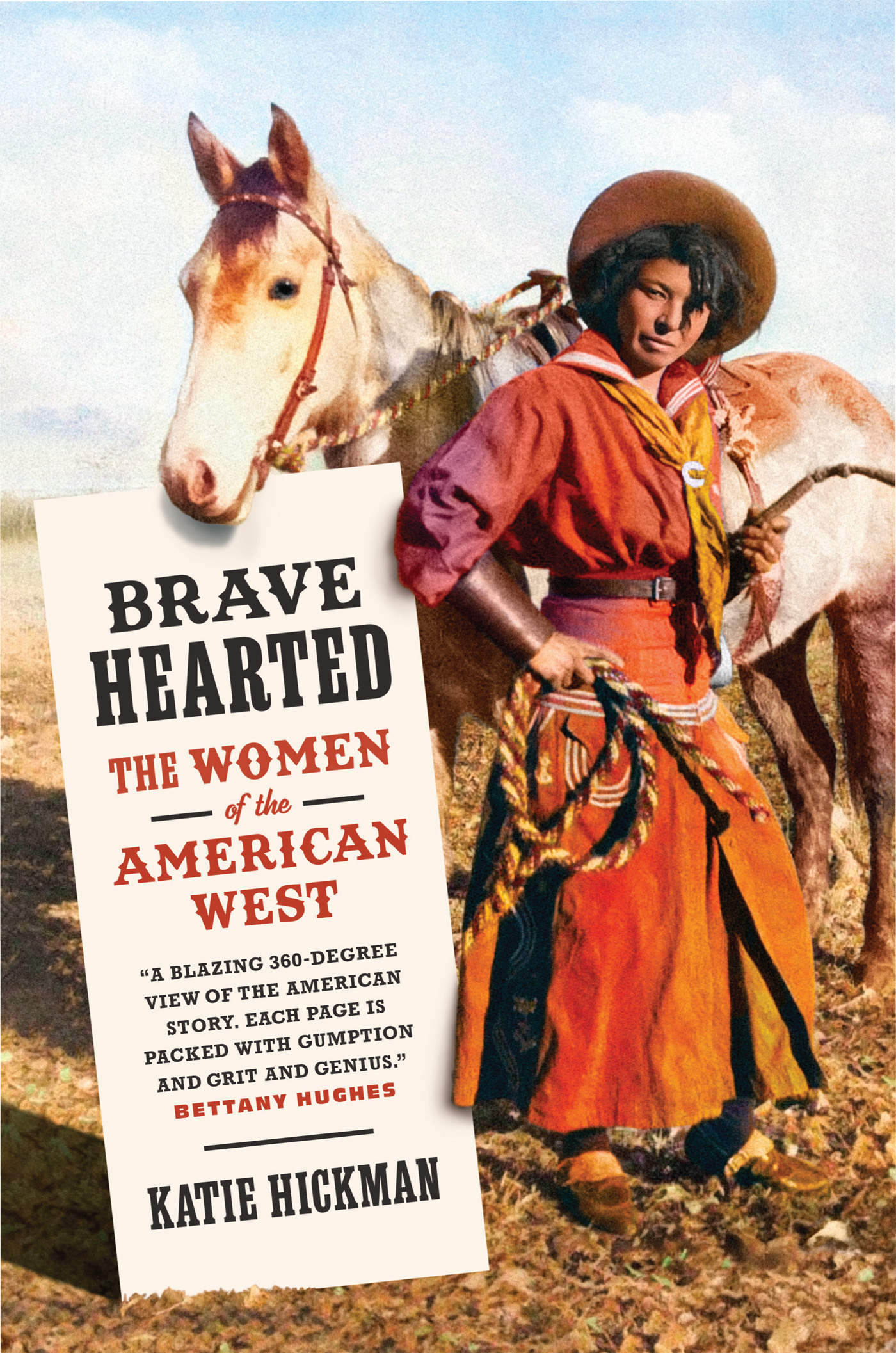

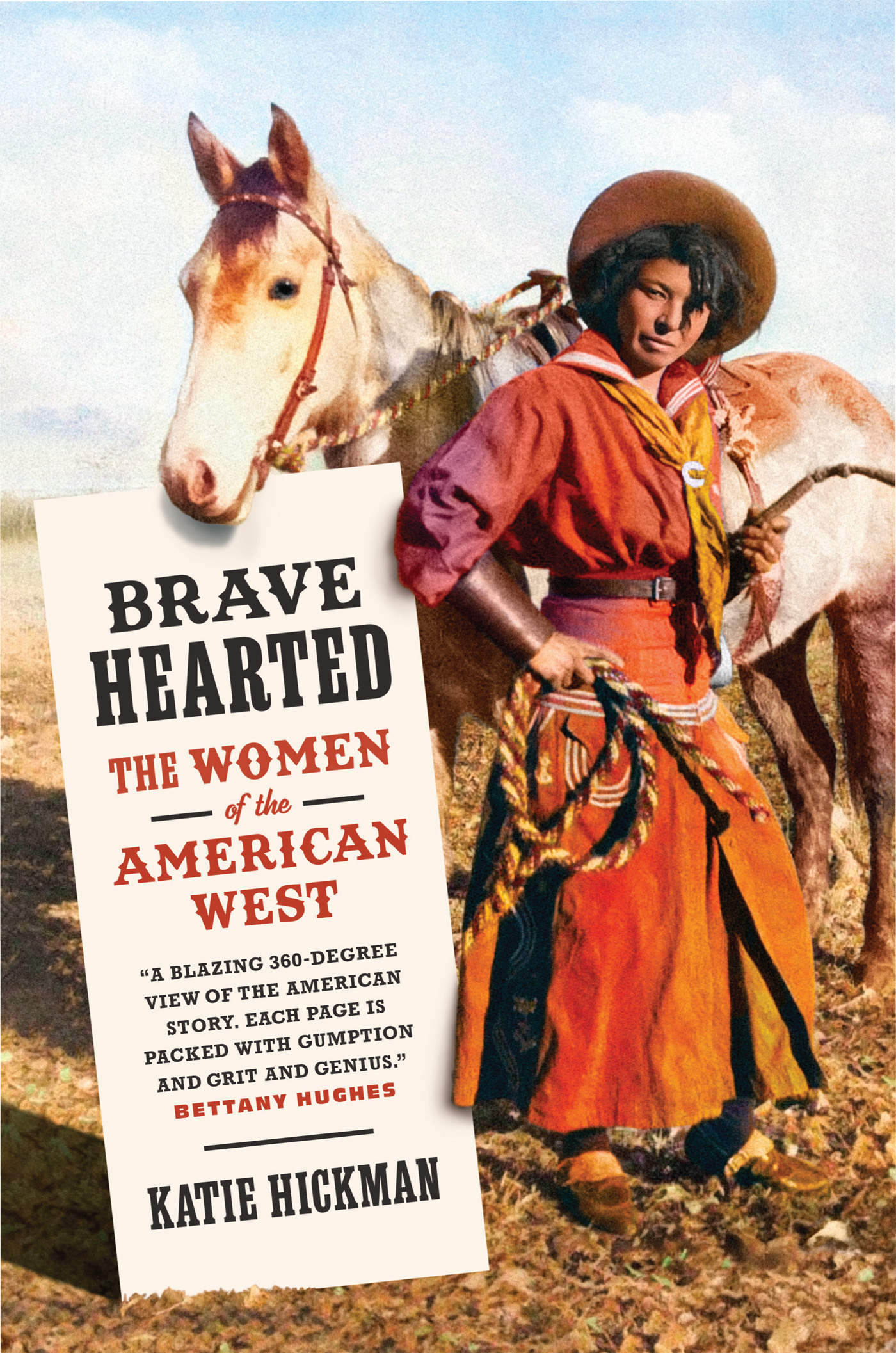

Jacket design by Strick & Williams; Jacket photograph of Nellie Brown, African American cowgirl, ca. 1880s, courtesy of Alamy Stock Photo

Interior design by Meighan Cavanaugh

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available Upon Request

ISBN 978-1-954118-17-1 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-954118-18-8 (eBook)

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my granddaughter, Eva, brave and beloved

Contents

: Geopolitical map of North America in 1836

: The Oregon and California Trails

: The Santa Fe and Gila Trails

: The Bozeman Trail

: USA in 1880

The word Sioux has been used as a blanket term for seven related and allied people, known as the Oceti Sakowin, meaning the Seven Council Fires. Only one of these people, the Lakota, come into this book.

Also known as the Tetonwan, or Teton people, the Lakota were made up of seven different Tribes, or bands, which were in turn divided into many smaller groups, also referred to as bands. The seven principal Lakota bands sometimes had more than one name; for clarity I have put the secondary French or English name in brackets.

They are the Hunkpapa (Josephine Waggoners mothers band), Minneconjou, Oglala, Sans Arc, Sicangu (meaning burned thighs and therefore sometimes referred to as BrulSusan Bordeauxs mothers band), Sihasapa (Blackfeet), and Oohenumpa (meaning two boilings and therefore also known as Two Kettles). In the nineteenth century, any or all these bands were often referred to interchangeably by whites under the blanket name of Sioux.

Lakota should not be confused with Dakota, which is a blanket term for the four eastern people of the Oceti Sakowin.

I t has been said that all American heroes are western heroes, and in the past, of course, almost all these heroes have been men.

For all the considerable work done by historians over the last fifty years to correct that imbalance, in popular imagination the Wild West is still a mans world. Served up to us as entertainment, high on thrills if short on historical accuracy, to this day our masculine images of the Westof trappers and huntsmen, of gunslingers, outlaws, and train robbers, of cowboys and gold seekersare an indelible part of Americas foundation myth. Immortalized in a thousand ballads, novels, movies, and television shows, the names of men like Buffalo Bill, Wyatt Earp, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid still spring easily to our lips. But for all their enduring appeal, not one of them was more than a walk-on part in an epic story that transcends them all.

Womens experiences are the very core of any true understanding of the reality of the American West, which is not so much a story about gunslingers and cowboys, although they play their part, but a story about one of the largest and most tumultuous mass migrations in history.

When this great migration began, in 1840, the United States of America consisted of just twenty-six states, covering a landmass that was only a fraction of the size it is now. In those days, the frontier was more of a vaguely defined idea than an actual place, and one that was in a continual state of flux. Some Americans might have seen it as anywhere west of the Mississippi River, particularly the furthermost borders of the newly created states of Missouri and Arkansas, and what (until July 1836) was then still known as Michigan Territory. But for many others it lay, for all practical purposes, along a particular stretch of the Missouri River, the great tributary of the Mississippi, where it flows along the western periphery of present-day Iowa and Missouri.

Beyond this, as the crow flies, lay two thousand miles of prairie, mountain, and desert, much of it designated on contemporary maps as either Indian Territory or, simply, Unorganized Territory. California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, parts of Colorado and Wyoming, and the whole of Texas were at that time still Mexican sovereign territory. Present-day Oregon and Washington States, and large parts of Idaho and Montana, were lands disputed between the US and Britain but as yet belonged to neither. The British-owned Hudsons Bay Company had a small but vigorous settlement, Fort Vancouver, on the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest, but, with the exception of small numbers of traders and trappers and the odd missionary, the rest of this vast continental landmass was almost entirely untouched by whites: a wilderness of almost unimaginable size and beauty.

The westward migrations started slowly. In 1836, two Presbyterian missionaries, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding, became the first white women ever to attempt what was then an unheard-of journey for females: a 2,200-mile overland trek, from the Missouri frontier, across the Great Plains and over the Rocky Mountains to Oregon country. Encouraged by their success, two years later in 1838 four more missionaries, together with their husbands, joined them in the Pacific Northwest.

The news of these groundbreaking journeys spread fast. If missionaries could endure them, then why not other women settlers too?

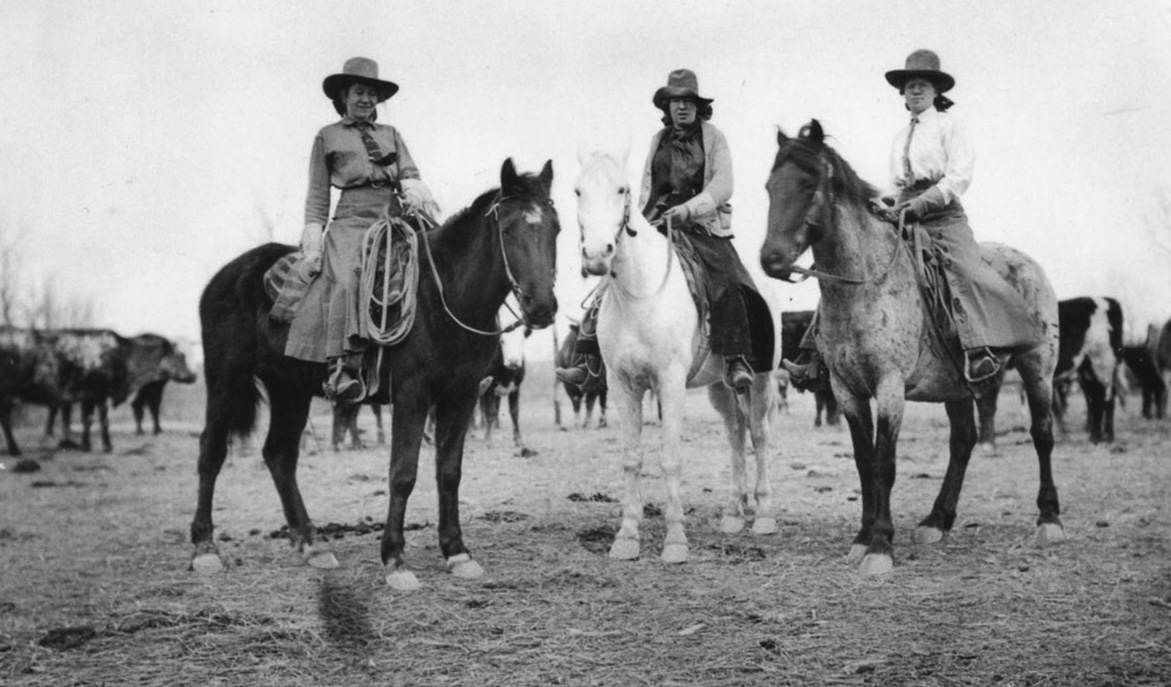

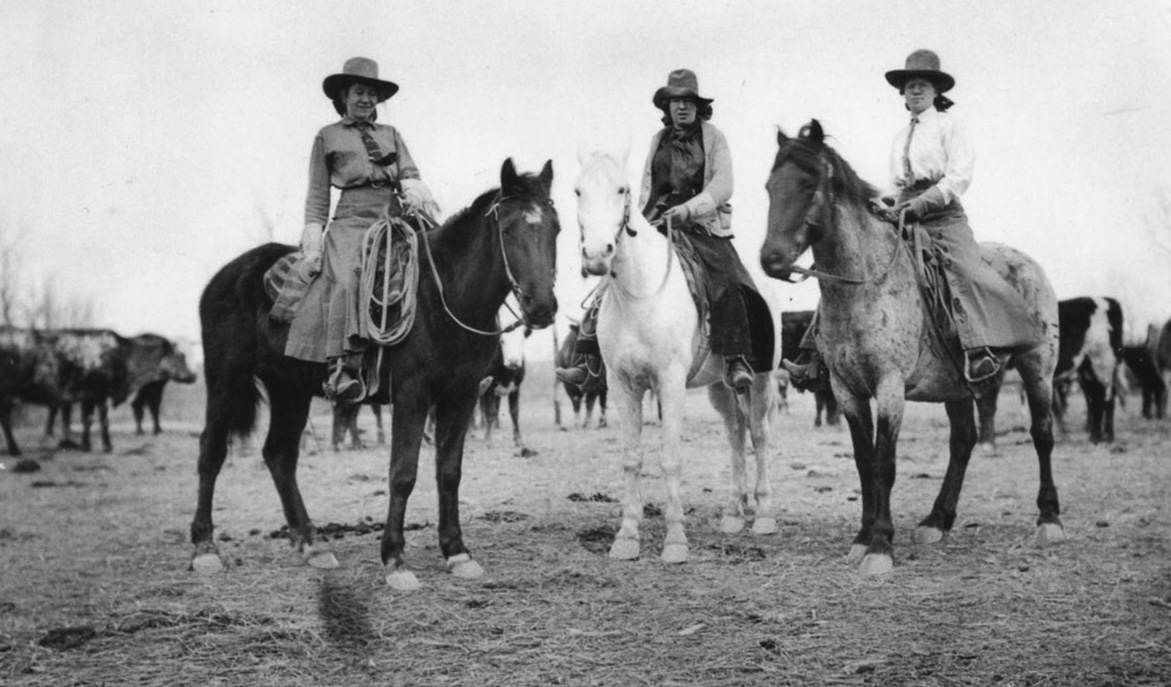

Women on horseback

While small numbers of American men had gone west before this time, their presence had for the most part been either transitory or seasonal, usually in line with the hunting and trapping year. It was clear that long-term settlement of these lands could not be achieved by men alone. It was only when women could be persuaded to go west alongside their men that the business of putting down permanent roots could begin. Homesteads and farms would then be built, the land would be plowed and crops sown, animals bred and husbanded. Most importantly, future generations would be born to carry on the work their parents had begun. The presence of white women would change everything.

Beginning in 1840, at least one settler familyMary and Joel Walker and their four childrenwas emboldened to follow in the missionaries footsteps, making the overland journey to Oregon in search of free land and new lives. In 1841, a hundred settlers made the journey. In 1842, it was two hundred. In 1843, a thousand. The year after that the numbers doubled again. Soon, stories about Oregon country began to percolate back East, each one taller than the next, and then so magnified that Oregon became known as an almost mythic paradisethe first of many utopias white Americans would look for in the West. Oregon country, it was said, was a land of milk and honey where vegetables grew to prodigious size and the rain only ever fell as gentle dew. With each passing year, the numbers of hopefuls setting out West from the Missouri borderlands grew.

Next page