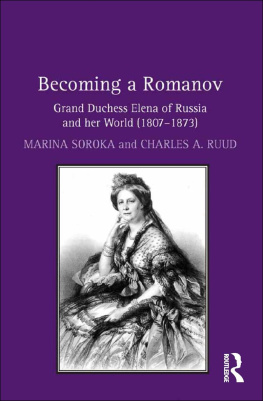

BECOMING A ROMANOV.

GRAND DUCHESS ELENA OF RUSSIA

AND HER WORLD (18071873)

First published 2015 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Marina Soroka and Charles A. Ruud 2015

Marina Soroka and Charles A. Ruud have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Soroka, Marina.

Becoming a Romanov : Grand Duchess Elena of Russia and her world (1807-1873) / by Marina Soroka and Charles A. Ruud.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4724-5701-1 (hardcover) -- ISBN 978-1-3155-6882-9 (ebook) -- ISBN 978-1-3171-7586-5 (ePub) 1. Elena Pavlovna, Grand Duchess of Russia, 1807-1873. 2. Princesses--Russia--Biography. 3. Nobility--Russia--Biography. 4. Romanov, House of--Biography. 5. Women social reformers--Russia--Biography. 6. Women--Political activity--Russia--History--19th century. 7. Serfs--Emancipation--Russia--History--19th century. 8. Russia--History--Alexander II, 1855-1881. 9. Russia--Politics and government--1855-1881. 10. Political culture--Russia--History--19th century. I. Ruud, Charles A., 1933- II. Title.

DK209.6.E38S67 2018

947.081092--dc23

[B]

2014049239

ISBN: 9781472457011 (hbk)

ISBN: 9781315568829 (ebk-PDF)

ISBN: 9781317175865 (ebk-ePUB)

Preface

Elena Pavlovna Romanova began her life as a royal princess of Wrttemberg in 1807; she died a Russian grand duchess in 1873. She is the only female Romanov whose name merits mention in any narrative of Russian history after the Crimean War because of her contributions to social welfare, medicine, science, music, and the emancipation of serfs in 1861.

However, she has remained an elusive figure, often mentioned but never explained. A publicist in 1882 provided a reason for the reluctance of biographers in imperial Russia. They were fearful of hurting the self-esteem of the living by rendering justice to the deceased,1 as none of the Romanovs of the late empire could match Elena Pavlovnas accomplishments or her achievements. In the early 1900s Anatoly Fedorovich Koni, a celebrated legal expert and publicist, collected some materials for her biography, but all he did was publish an essay.

After the revolution of 1917, in the Soviet times, writing about the Romanovs above all writing favourably was discouraged. Nevertheless, Elena Pavlovnas role in the abolition of serfdom and the founding of the first Russian community of nurses was sometimes mentioned. Her name also appeared in the albums featuring the masterpieces from the Russian State Museum housed in her palace. A prominent Soviet novelist Sergei Sergeev-Tsensky slipped her name into his fictionalized narrative of the Crimean War, Sevastopol Toils. It was exceptional for the Soviet period and proved the lasting quality of her contribution.

In todays Russia this benign semi-neglect continues: anniversaries of the causes which she supported the Red Cross, the Petersburg conservatory, hospitals and the emancipation of serfs, among them are occasions to remember her. Several essays dedicated to Elena Pavlovna that have appeared are re-worked conference presentations and their scope is necessarily limited.

In 1991 she was featured in a short German monograph about August von Haxthausen, Elena Pavlovnas Prussian friend and protg,2 but the author focused on one issue, emancipation, and Haxthausens intellectual contribution to it.

And yet Elena Pavlovna took it for granted that someone would write a record of her life and as early as 1843 instructed the executors of her will to burn all her personal documents except those which her official biographer would need. As a result, her archive largely contains numerous official reports, newspaper articles, business proposals and memoranda, as well as documents relating to household and court administration. Just as she wished, the breadth of her civic and cultural interests is amply shown; her private world and her views are obliterated as much as possible.

Her diaries were apparently destroyed, save for a dozen pages; so was most of her correspondence with her parents and her friends. She often asked her correspondents to burn her letters, and, unfortunately for historians, they usually complied. We know of her close intellectual friendship with several remarkable personalities of the nineteenth-century Russia but few letters survived. As early as 1847 a German diplomat and biographer Karl-August Varnhagen von Ense was burning to ask the grand duchess to let him read her correspondence with a deceased Russian political thinker, Prince Petr Kozlovsky, which he knew existed; in the 1860s a Swiss theologian Ernest Naville wrote an important memorandum for Elena Pavlovna, but there are no traces of any of these documents in her vast archive. The same applies to her letters to the Evangelical proselytizer Count Alexandre de Saint George.

Still, there are scattered records from her contemporaries and we have found them helpful in trying to see the person behind the public figure. Her voice is best heard in her surviving letters to General Pavel Kiselev, a close friend for forty years. She wrote like she spoke: impetuously, unhesitatingly, never at a loss for words or for ideas. She could go on for five-six pages in a large sprawling hand, without making corrections.

Another friend, Count Sergei Uvarov, kept Elena Pavlovnas expansive, emotional letters tidily bound in a volume of letters he received from the Romanovs now at the Historical Museum in Moscow.3 Field Marshal Fedor Berg preserved her letters written at the time of the Polish insurrection of 1863. Two ladies of her court also saved her letters. These previously unused documents were essential in understanding the person who played an important role in Russias history despite her insistence that she had led a life of contemplation.

Her marriage in 1824 to the youngest brother of Emperor Alexander I, Mikhail Pavlovich, was ill-fated. In an epoch when happiness was synonymous with love, Elena Pavlovna and her husband evoked pity from their relatives and acquaintances for their loveless marriage.

Her strong personality ensured that she achieved an unprecedented degree of independence in the Romanov family. She used it to demonstrate what a determined and competent Romanov could accomplish. Like other royal philanthropists she endowed hospitals, schools, scientific projects and soup kitchens for the poor. The Russian Academy of Sciences holds her weighty collection of scholarly books. Russia owes to her its first lay community of nurses (the precursor of the Russian Red Cross), as well as the first conservatory of music. Her greatest service to Russia was her help to Alexander II in the daunting enterprise of ending serfdom.