This edition copyright A Vincent McInerney 2012

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84832 125 0

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 78346 876 8

PRC ISBN: 978 1 78346 643 6

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system, without

prior permission in writing of both the copyright

owner and the above publisher.

The right of Vincent McInerney to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset and designed by M.A.T.S. Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire

Introduction

I have a horror of death; the dead are soon forgotten. But when I die theyll have to remember me.

DURING THE NINETEENTH century it became increasingly common for merchant service masters to take their wives to sea, particularly in the whaling industry, where voyages of two or three years were not uncommon. Reflecting the sailors traditional dislike of women on board seen as unlucky by the superstitious and disruptive by the more rational these ships were derisively dubbed Hen Frigates; although they have been the fashionable subject of academic interest in recent years, there is not much published literature by the women themselves, and the wealth of journals are little known and not easily accessible. Among the first, and most accomplished, is Abby Morrells account of a voyage between 1829 and 1831 that took her from New England to the South Pacific. Her husband Benjamin was in the sealing trade but was a keen explorer, and his adventurous spirit led him and his wife into situations normally well outside the world of the Hen Frigate.

Curiously, Benjamin also wrote an account of this voyage, but since he was described by a contemporary as the greatest liar in the Pacific, his wifes may be a better record of what actually happened, even when dealing with such dramatic incidents as a murderous attack by cannibal islanders. Her account certainly enjoyed larger sales. Apart from the descriptions of exotic places, much of the interest in this book is the traditional, centuries-old world of the sailor as seen through the eyes of a thoughtful and well-educated woman. As such it heads a long line of improving books aimed at ameliorating the seamans lot.

Born in New York in 1809, the newly wed Abby Morrell insisted on accompanying her husband on a sealing voyage that was to last three years; her brother also went along on this voyage. However, after giving birth to a second son following their return in 1831, Abby remained at home. As a further example of wifely sacrifice, she withheld the publication of her own book until after her husbands was released.

This volume of Seafarers Voices seems to be unique in three ways. It is the first American account (perhaps the first ever) of a deep-sea voyage left to us by the wife of a merchant captain, who accompanied her husband on the voyage in question. Further, it is possibly the only account where both the husband and the wife have left complementary versions of the same trip, providing a unique insight into a husband and wife team working together and what each considered important, or came to consider important, on the voyage. Finally, many years before Samuel Plimsoll (1834-1898), the seamans friend, made his pleas for the amelioration of the lot of the common sailor in books such as Our Seamen (1873), Abby Morrell makes impassioned but reasoned arguments for better conditions and educational opportunities to be made available to the men before the mast, a call that has still not even today been addressed by many of the worlds biggest shipping lines, concerns, and consortiums.

Abby Morrell was born Abby Jane Wood in 1809, the daughter of Captain John Wood, who died at New Orleans in 1811 while master of the ship Indian Hunter, a man, we are told, who was judged by his contemporaries as being of great integrity. On his death, Abby Wood Morrells mother placed their property in the hands of a person who by intention or mismanagement lost or retained the whole of it. Matters were rescued when her mother was consoled both by religion and by remarriage, in 1814, to a Mr Burritt Keeler. This stepfather Abby Morrell came to love and feel for as much as if he were naturally responsible for my existence and care. She adds that she had a plain and regular education; and that one of her greatest enjoyments was attending St Pauls Trinity Church, New York.

Early in the year 1824, when she was fifteen, her

Abby Wood married Benjamin Morrell on 29 June 1824. Morrell had been married before; his first wife and their two children had died between 1822 and 1824 whilst he was at sea. A short time after this second marriage, according to Abbys account, Benjamin Morrell informed his wife that he would be leaving on a voyage expected to last about two years, and three weeks later he did so.

Morrell returned on 9 May 1826, two months short of two years, before making a number of short European voyages, during which time a son had been born to the couple. Then in June 1828 Morrell sailed again for the South Seas, this time the separation being eleven months. On his return, his wife determined that if he ever went to sea again, I would accompany him. On hearing new plans for another trading voyage to the Pacific, she now ventured to mention my accompanying him. At first he apparently would not hear of it; but when I insisted (as far as affectionate obedience could insist) he at last reluctantly yielded and put the best side outwards.

Although voyaging under these circumstances [might] seem a most remarkable challenge, as Joan Druett points out in her history of those wives of merchant captains who went to sea, Abby Morrell was only one amongst a great multitude of women who took up the same strange existence in the blue-water trade, yet astonishingly most of them were, like Abby, ordinary, conservative, middle-class women, and not rebels or adventurers, even if their husbands could be described as such.

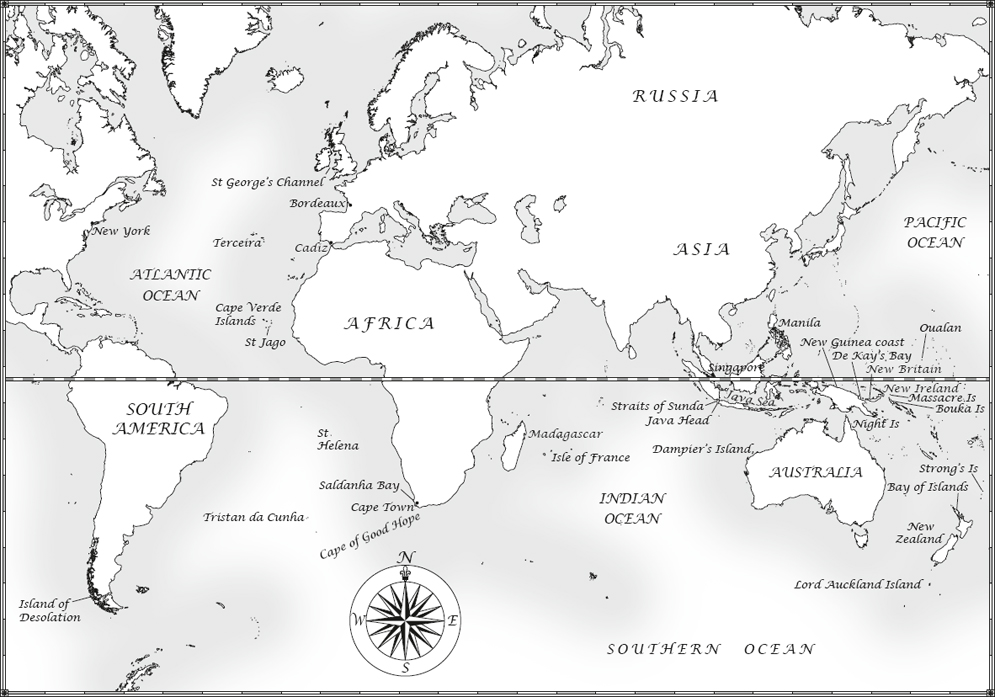

On 2 September 1829, Captain and Mrs Morrell, with twenty-three sailors (one of whom was Mrs Morrells brother) embarked on the schooner Antarctic for the South Pacific, via the Cape of Good Hope. Once there, their aim was to try for a cargo of seal, bche-de-mer (sea cucumbers), and whatever else might be available to render a profitable voyage.

Once out of sight of New York, it seemed at first that the voyage had been a mistake: Mrs Morrell became anxious for the welfare of her young son who had been left with her mother, and she immediately fell prey to However, Abby Morrell eventually gained her sea legs, and perhaps also became reconciled to her absence from her son, as the account only mentions him again briefly before they are reunited at the end of the voyage.