This ebook edition first published in the United Kingdom in 2013 by University of Plymouth Press, Scott Building, Drake Circus, Plymouth, Devon, PL4 8AA, United Kingdom.

eBook ISBN 978-1-84102-336-6

University of Plymouth Press 2013

The rights of Walter Jones of this work have been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A paperback CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library 978-1-841022-286-4

Publisher: Paul Honeywill, Publishing Assistants: Charlotte Carey and Natalie Haly, Production Assistant: Rebecca Drees

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of UPP. Any person who carries out any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

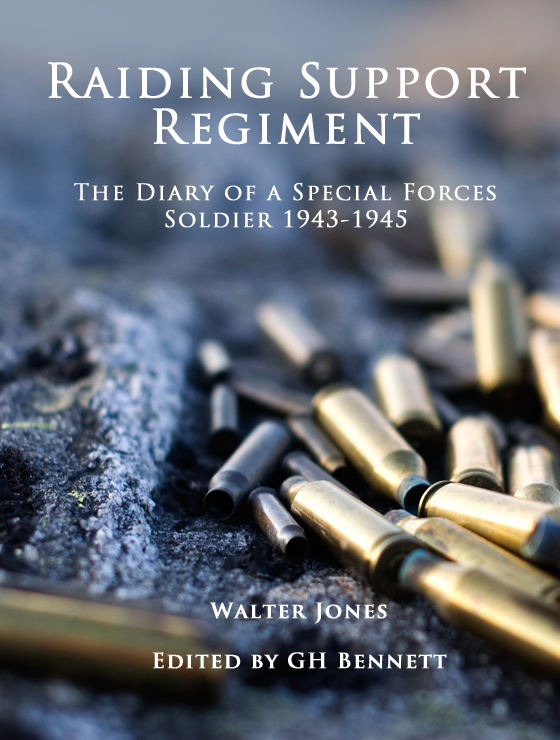

Cover Peter Lvstrm, images throughout Walter Jones

Foreword

Albert Jones

We were standing at our front door in Liverpool my mother, brother Walter and I when a neighbour, Mrs Fields, came up to us in tears. She was carrying a telegram that said that her son Ronnie a former school friend of Walter was missing, believed killed in action in France. The timing could not have been worse: we were on the doorstep to say goodbye to Walter, my mother was already trying hard but unsuccessfully not to cry. Walter was returning to his unit after embarkation leave, and we had no idea when or if we would see him again.

Ours was just one among the many families divided by the war. We were lucky: we all survived, our mother living just long enough to see Walter return. But many families did not and no family that came through the war was ever quite the same. When World War II began on 3rd September, 1939, Walter had already volunteered for the army while my brother Harry and I, aged 14 and 11 respectively, had been evacuated to the country. Wal he was always Wal at home to distinguish him from our father, who was also Walter had been a hero to me as a child: I tried to write like him, I was a jazz fan and an avid Everton supporter. Although we three brothers attended the same elementary school and spent our pre-war family holidays together in Lytham and in southern Ireland, our age gap (or so it seemed then) meant that contact was brief and infrequent he was still our big brother and we did not start to get to know each other as friends until we were approaching middle age. There was a succession of reasons: in the early part of the war our meetings were restricted to his rare spells on leave, then the family moved away from Liverpool in the hope (a vain one as it turned out) of escaping the worst of the Blitz. By the time Walter had been demobilised I was in the RAF, and by the time I was demobilised he had moved to make his life in the south of England. Then I emigrated to New Zealand (where, like Walter, I became an accountant) and by the time I returned 11 years later, he and his family lived in Devon.

It was only then that we started to make up for lost time, and I have many happy memories of those years: of shared humour; of Middlesex Sevens weekends; of indulging our mutual love of jazz; and of visits to Liverpool with Harry to visit ageing relatives and watch our beloved Everton. Other treasured memories of our adventures together include a family history tour that we three made to southern Ireland, involving copious tastings of the local brew and our installation as Freemen of Drogheda, our mothers home city; and in later years, a trip to New York, Washington, Philadelphia and to our joint musical heritage, New Orleans.

For many years, he had talked to me about those precious (and illicit) diaries that he had carried with him throughout the war. They fitted neatly into the battledress pocket that was supposed to hold his First Aid kit fortunately he was never injured. But it was not until he was winding down to retirement some 40 years later that he felt compelled to begin the organisation, revision and research necessary for the completion of his memoir.

By the time the work was completed he had written half a million words five times the length of this book. It was a happy coincidence that much of the research was done at the Public Record Office in Kew a short walk from where I lived at the time.

It was one of the great disappointments of his military career that when there was an urgent need for bomber crews to begin, finally, to carry the war to the enemy, he was the only one among his group of colleagues to be turned down, which he always assumed was because of his schooling. In many ways it may have turned out to be a blessing, not only because it probably improved his chances of survival Bomber Command had a less than 50% survival rate but also, if he had been accepted, we would have been deprived of this fascinating and moving account of Walters war.

Albert Jones February 2008

Introduction

G.H. Bennett

The Second World War witnessed a steady growth in the number and use of Special Forces units such as the Special Air Service (SAS), Special Boat Service (SBS), the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) and Popskis Private Army. The harsh climate and special nature of the battlefields in the Middle East were the cradle for emergence of units such as the SAS and LRDG. It took a special kind of soldier highly self reliant, physically and mentally tough to operate in the desert with minimum levels of support. Most special units were short-lived expedients to address particular tactical circumstances. Their personnel were renowned for their toughness, skill and ruthlessness. Their leaders, such as David Stirling of the SAS, would establish considerable reputations for their tactical vision, soldierly qualities and powers of leadership. By their very nature, Special Forces were lightly equipped. Whether for reconnaissance purposes or surprise attack, Allied Special Forces relied on speed, surprise, camouflage and evasion.