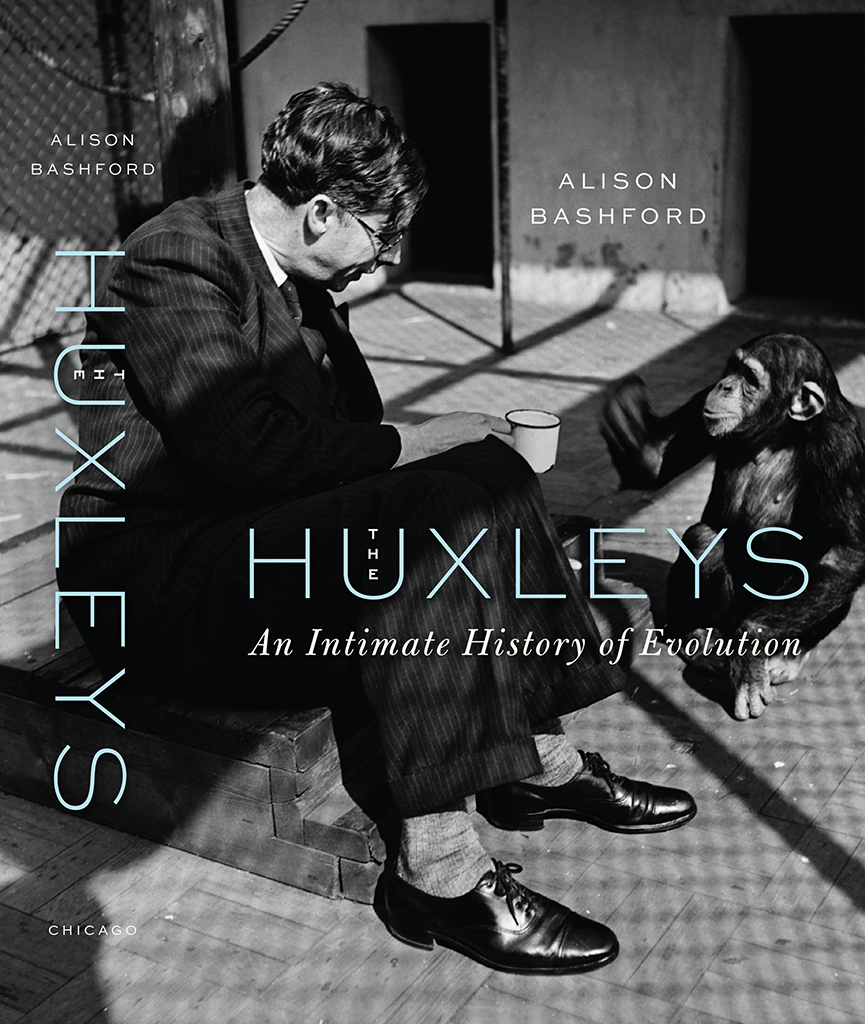

The Huxleys

An Intimate History of Evolution

ALISON BASHFORD

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

2022 by Alison Bashford

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-72011-1 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-82412-3 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226824123.001.0001

First published in the United Kingdom as An Intimate History of Evolution: The Story of the Huxley Family by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Random House UK, 2022.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bashford, Alison, 1963 author.

Title: The Huxleys : an intimate history of evolution / Alison Bashford.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022009756 | ISBN 9780226720111 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226824123 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Huxley, Thomas Henry, 18251895. | Huxley, Julian, 18871975. | Evolution (Biology)History.

Classification: LCC QH361 .B375 2022 | DDC 576.8dc23/eng/20220331

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022009756

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For

Keith Harvey Bashford, 19342022

Contents

List of Illustrations

Authors Note on Names

There are many Huxleys in this book. To distinguish between the two on whom I focus most closely, Thomas Henry Huxley and Julian Huxley, I use Huxley for the grandfather and Julian for the grandson.

Introduction

How are humans animal and how are we not? What is the nature of time and how old is the Earth itself? What might the planet look like with or without humans 10,000 years hence? More modestly, who asks such questions for a living, and who thinks they have the answers?

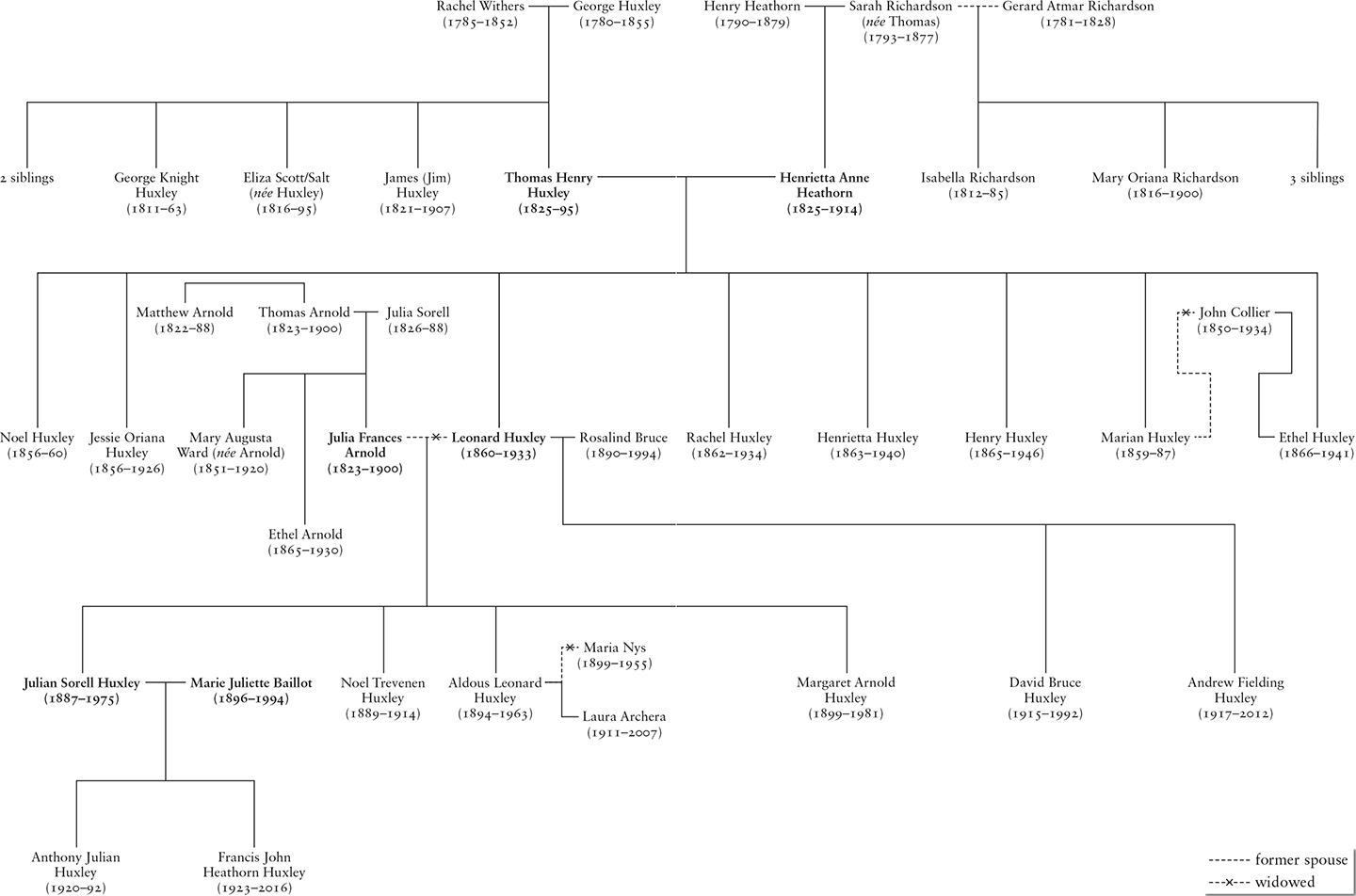

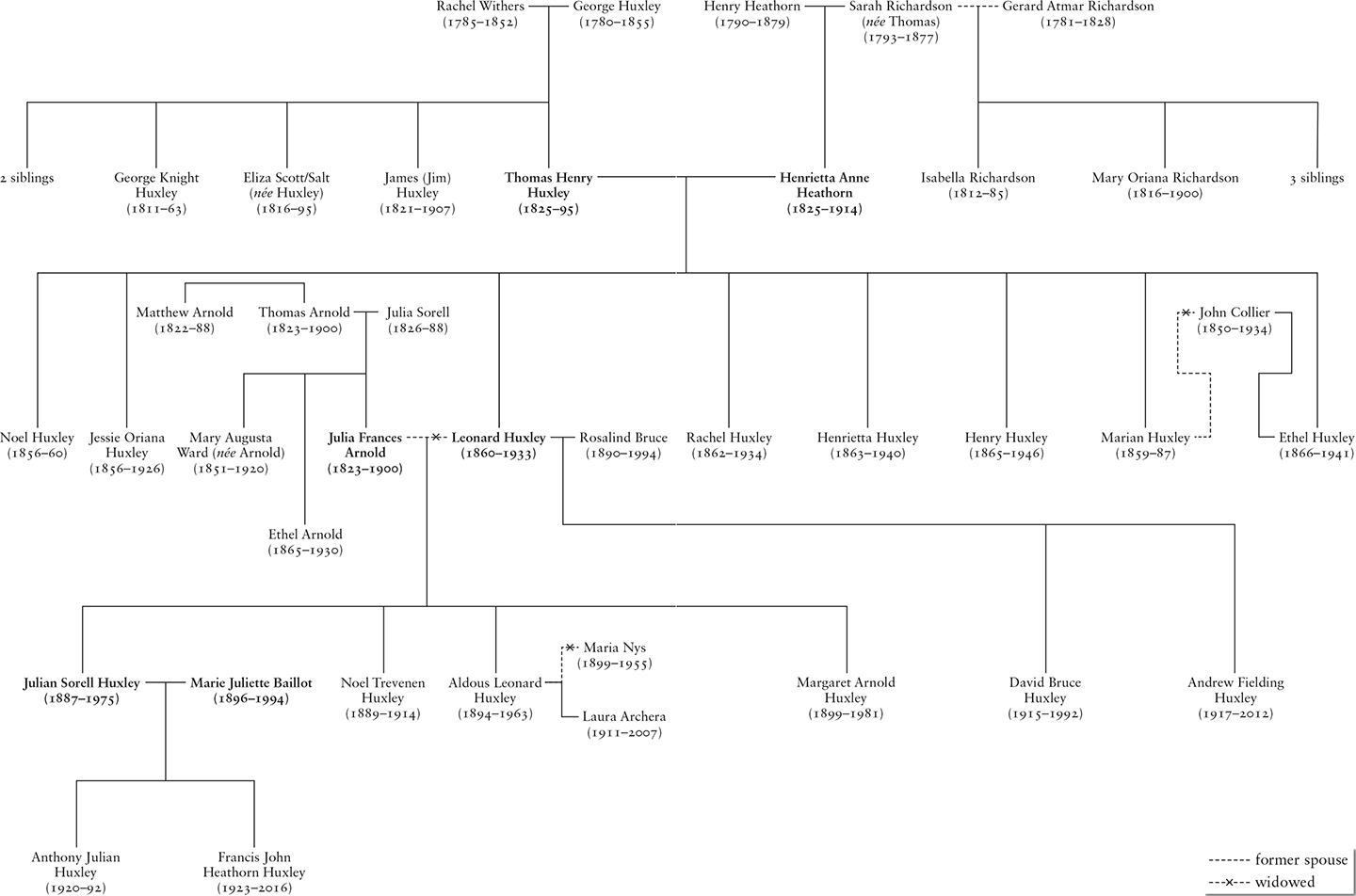

Thomas Henry Huxley and his grandson Julian Huxley did. In 1947 they featured in Life magazine, one dead, one living. At the photo shoot in his Hampstead library, Julian self-consciously arranged himself in front of a portrait of his grandfather (

The younger man constantly fashioned himself after his Victorian grandfather, pursuing those signature Huxley knowledge-quests, some profound, others simply grandiose. They were both remarkable and both, on occasion, tortured. Writing these natural scientists together permits a kind of time-lapse over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, precisely because they were so similar. We might even think of them as one very long-lived man, 18251975, whose vital dates bookended the colossal shifts in world history from the age of sail to the space age; from colonial wars to world wars to the Cold War; from a time when the Earth was 6,000 years old according to Genesis, to a time when it was 4.5 billion years old, according to rock samples returned from the Apollo missions.

Figure 0.1: Julian and Thomas Henry Huxley, trustees of evolution: Life magazine photo shoot, 1947.

Two other portraits help us understand these trustees of evolution, and how they were keen players in the great modern effort to comprehend and fix nature and culture. The likenesses are windows into their very different scientific souls, but we need not look into their eyes, rather at what they hold.

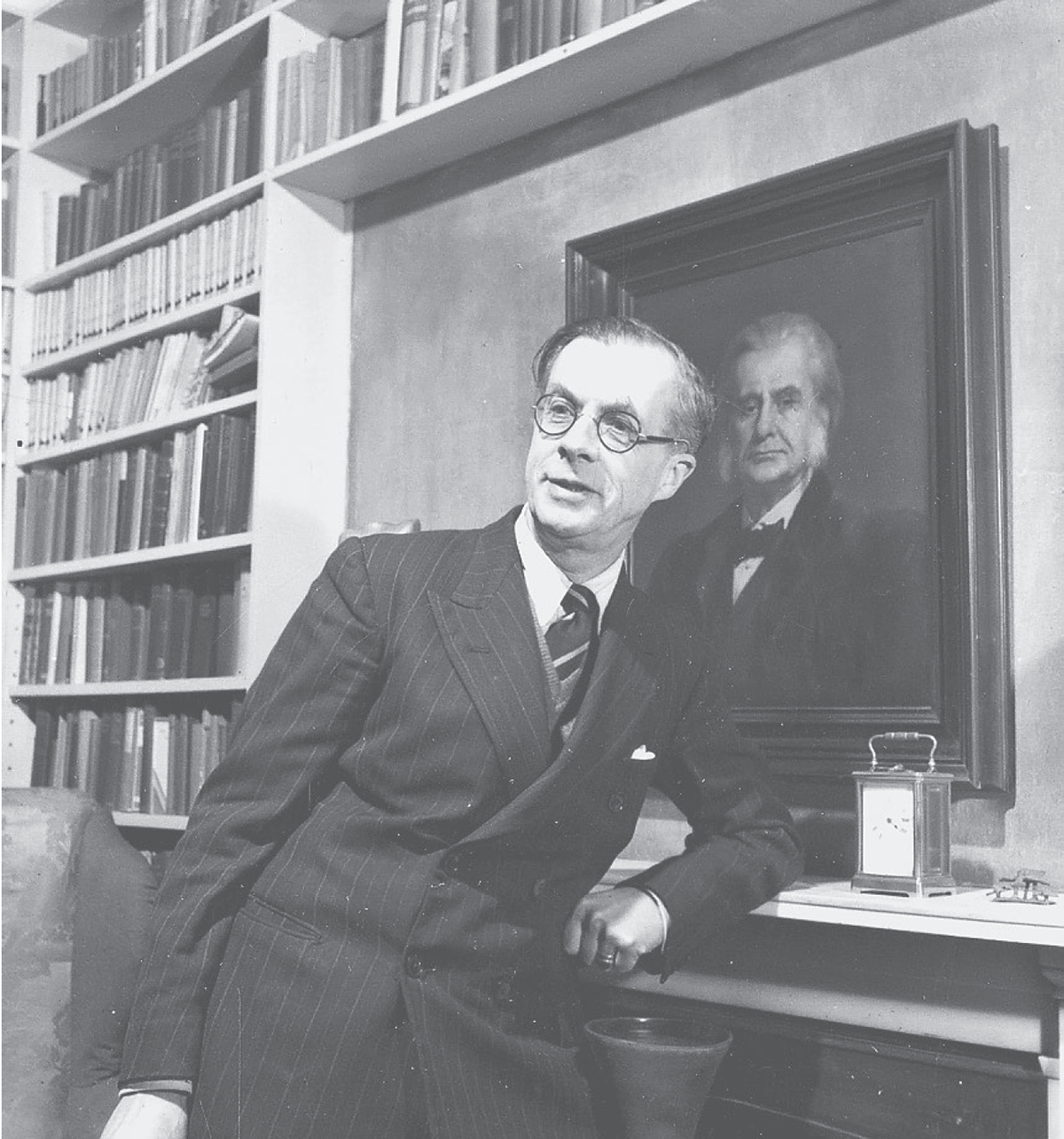

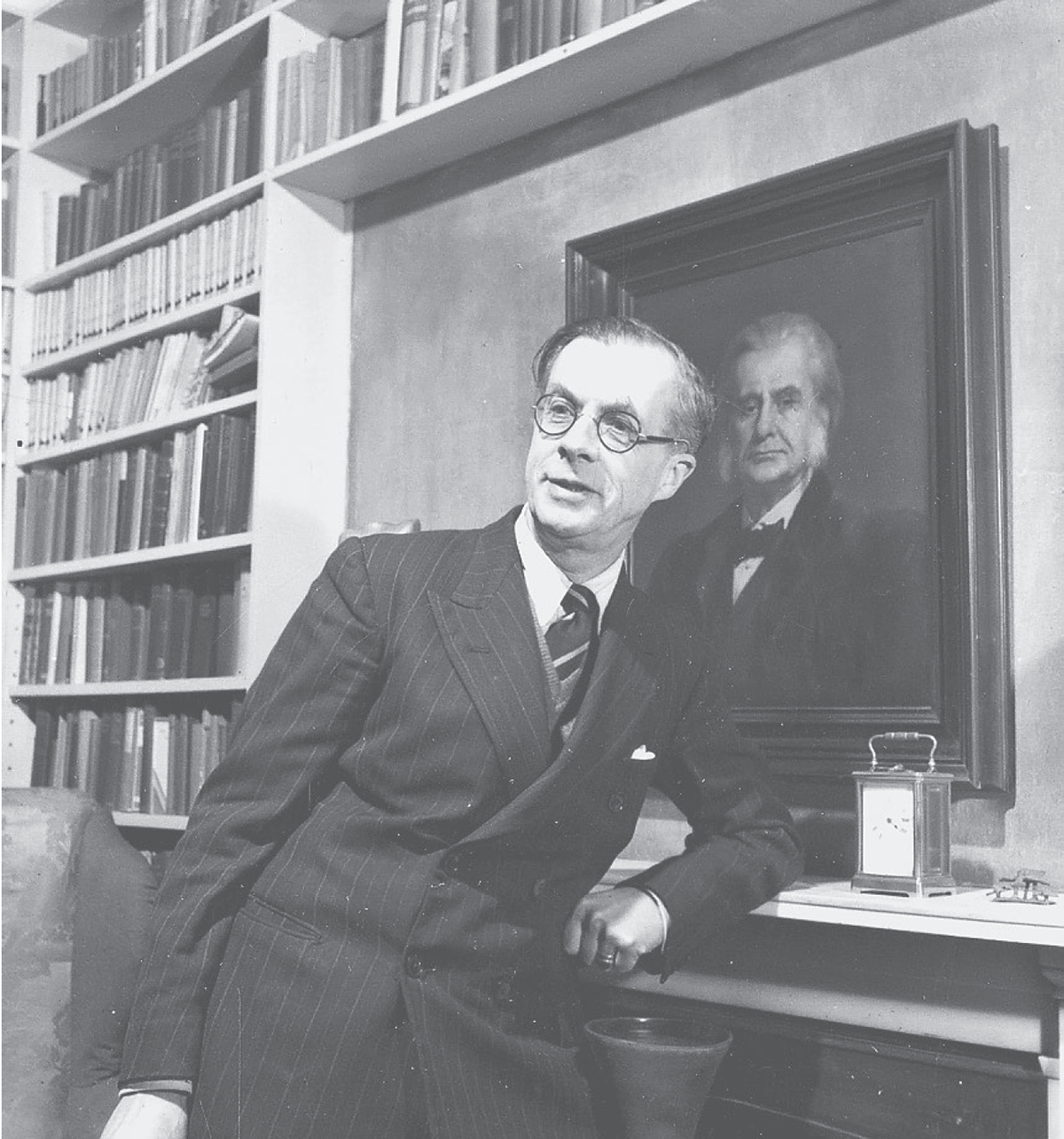

Julian holds culture, an Igbo wooden sculpture from Nigeria, bought on the cheap in his West African travels in 1943 ( He was self-fashioning his curiosity and his cosmopolitanism, as well as his scientific inheritance. Student and lover of nature, inheritor of agnostics, brother of Aldous, believer in evolution by natural selection, and (his own invention) evolutionary humanism, Julian was from the beginning inclined to culture. Even as a zoologist, he was foundational to ethology, the study of animals behaviour, how they and we act, think and even feel. Yet culture was itself part of evolution and technically so, not just loosely or illustratively. Human minds are unique in evolutionary terms, Julian always insisted, precisely because we can comprehend just that.

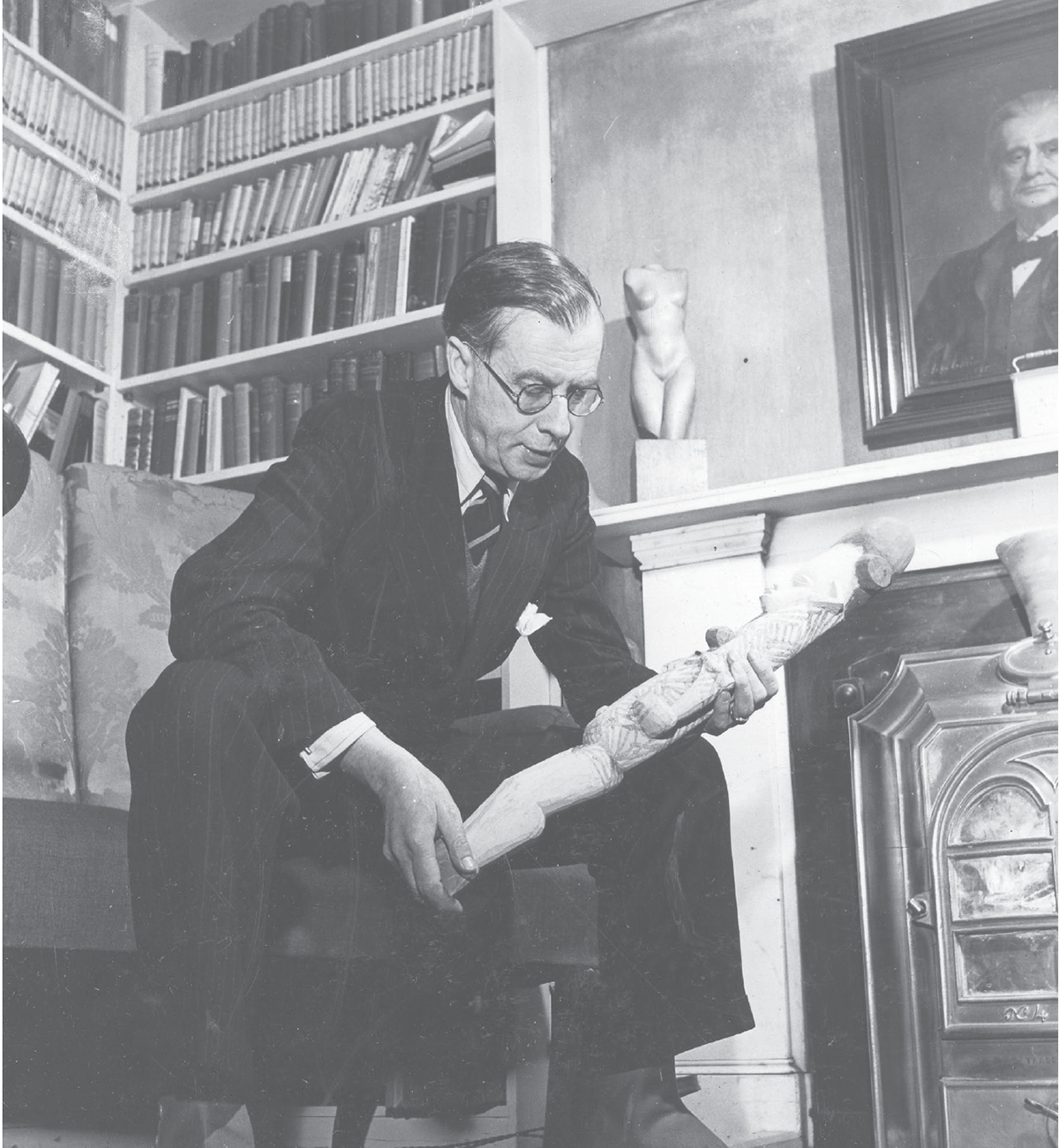

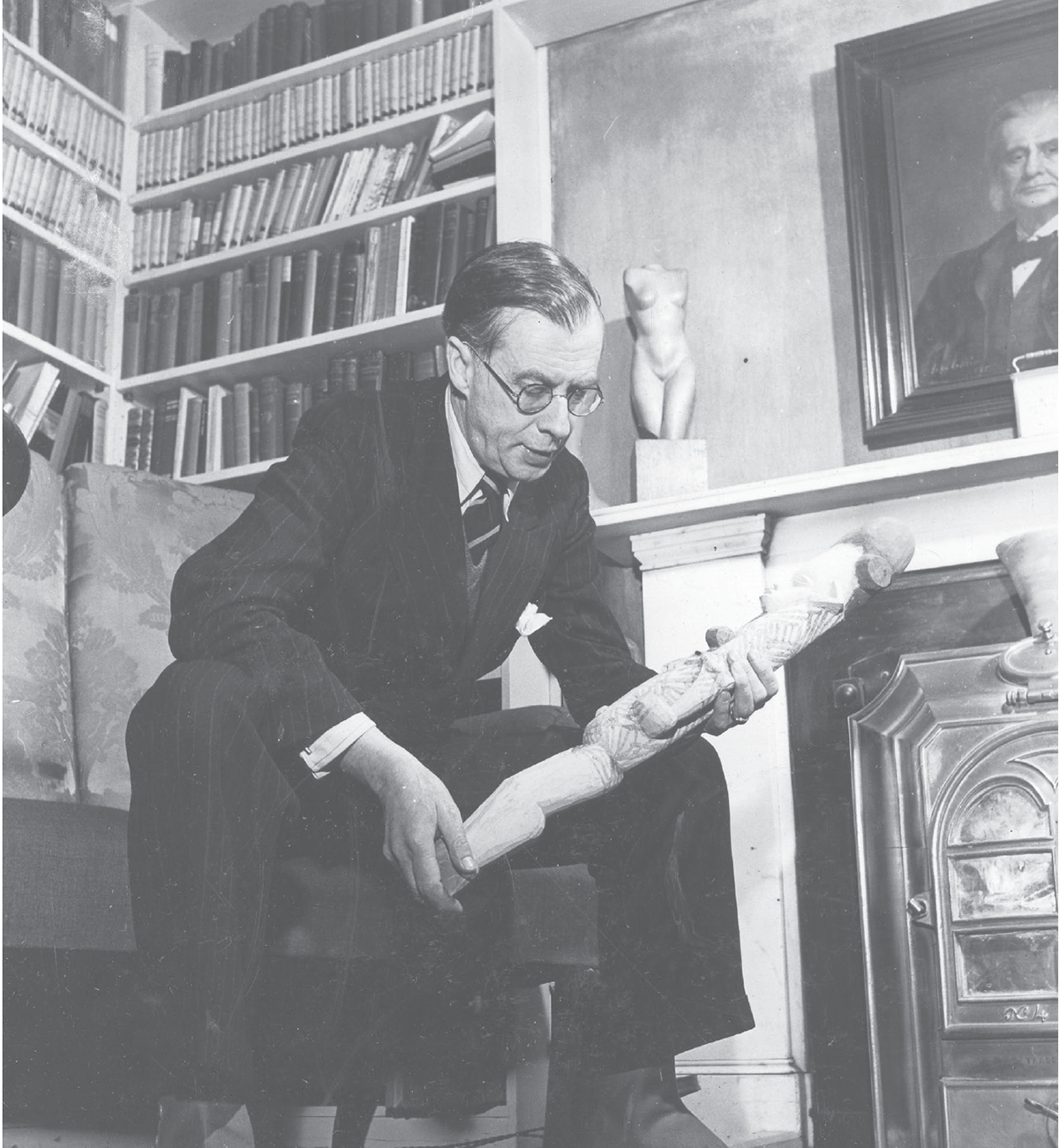

T. H. Huxley, by contrast, holds nature (

Figure 0.2: Julian Huxley and Culture: Life magazine photo shoot, 1947.

Figure 0.3: Thomas Henry Huxley and Nature: oil by John Collier, 1883.

Many would then, as now, rightly consider human remains to be somehow sacred, certainly as sacred as the effigy Julian held. Yet Huxley the grandfather comprehended nothing of the sort. Skulls were workaday material objects, fascinating, but in no sense sacrosanct. Neither in death nor in life was the human body the receptacle of a soul, at least we can never show that to be the case, Huxley the agnostic insisted. He battled his whole life for nature, and for a strictly scientific method to understand it.

The modernization of natural sciences of which Huxley was a key player, even dramaturge, challenged the magical and the supernatural. It heralded the death of the divine, disenchantment as the sociologist Weber had it, the death of God according to the philosopher Nietzsche. In different ways they were both responding to the ascendance of scientific naturalism that T. H. Huxley spearheaded, and in a German scholarly tradition in which Huxley was deeply learned self-taught, of course. There are no spirits, no Creator, no divine, at least none of which we can be sure. Wonderful! Huxley would have exclaimed had he lived long enough to read the great scholarly debates that unfolded on secularization and disenchantment over the twentieth century. And yet he might also have questioned why, then, his biologist grandson Julian was so drawn to sacred idols, studied parapsychology and wondered occasionally about ghosts; why his literary grandson Aldous sought radically other perceptions and doors into them; not to mention his anthropologist great-grandson, Francis Huxley, who became so immersed in the magical and the mystical, in voodoo and in rituals of sacralization, as to become himself a kind of animist.

One trajectory of this intimate history of evolution, according to the thesis of disenchantment, should be a history of secularization, a victory of T. H. Huxleys rational agnostics in a dynasty of scientists. In fact, it is a story of Huxley re-enchantment. Over three and four generations of modernity, the Huxleys searched proactively for something to put in the place of religion, compatible with Grandfathers scientific naturalism but somehow exceeding it. Julian ended up a kind of neo-Romantic naturalist, complete with visions and poetry, closer in some ways to the early nineteenth-century

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).