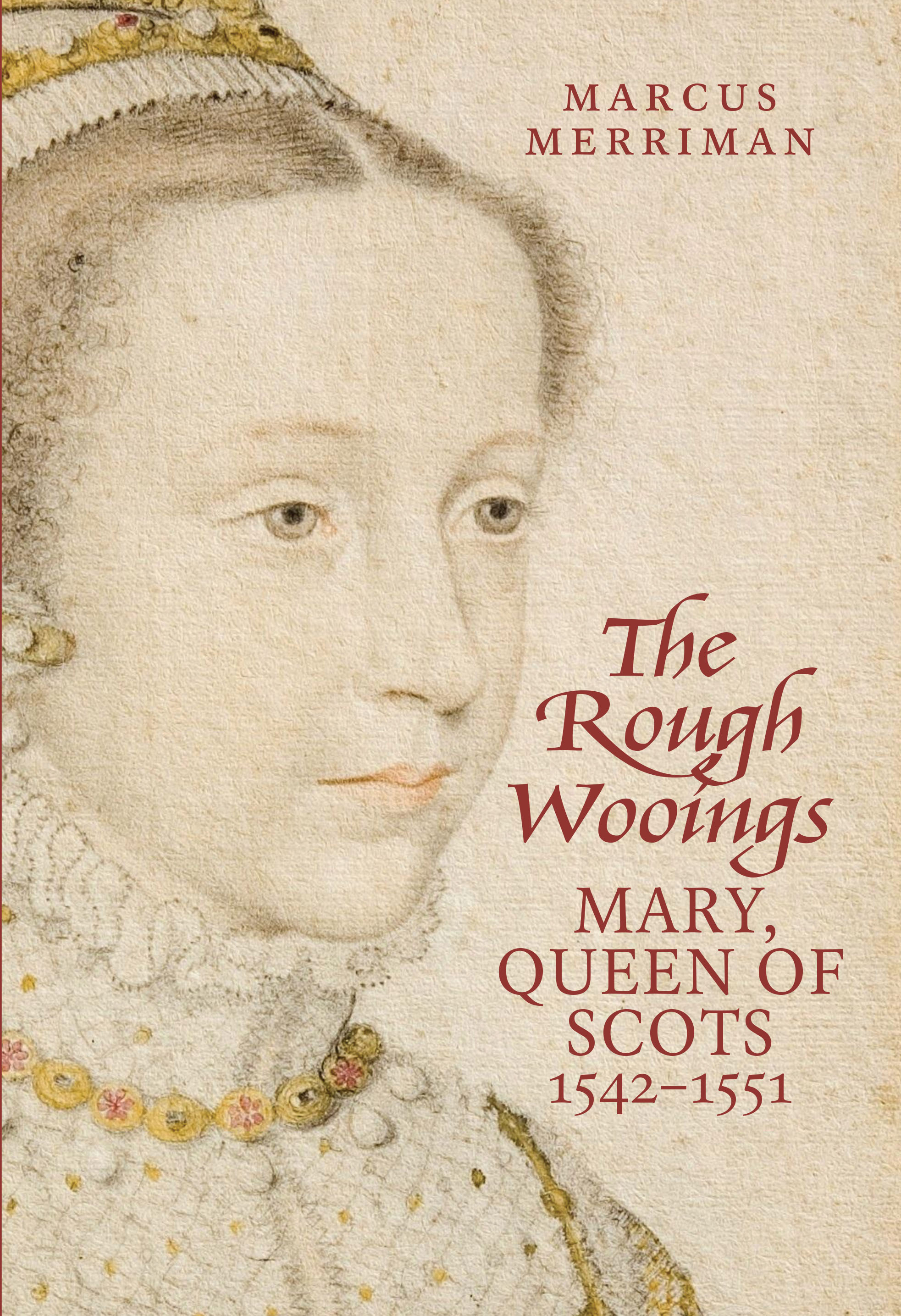

THE ROUGH WOOINGS

For

Catherine Ruth Merriman

Elizabeth Hannah Merriman

Nathaniel Paul Merriman

THE ROUGH WOOINGS

Mary Queen of Scots, 15421551

Marcus Merriman

This eBook was published in Great Britain in 2021 by John Donald, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

First published in Great Britain in 2000 by Tuckwell Press

Copyright Marcus Merriman, 2000

eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 393 4

The right of Marcus Merriman to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

The publishers gratefully acknowledge the support of the Strathmartine Trust towards the publication of this book

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Contents

Colour Plates

Illustrations, Diagrams, Maps and Family Trees

14.2 St. Marys Kirk, Haddington

B: Table showing English war costs overall and for Scotland in particular

Acknowledgements

I n 1797, John Pinkerton, then a mere thirty-nine years of age, published in London his two-volume masterwork, The History of Scotland from the Accession of the House of Stuart to that of Mary. His opening remarks strike a resonant chord in me: With a considerable degree of anxiety the author at length delivers to the public candour the greatest labour of his life. I am sixty and The Rough Wooings has been with me a long time. Pinkerton was overly conscious of what he saw as his failings but especially the cruel necessity of being his own pioneer, of proceeding as in an American forest, with most cautious steps through the swamps, and earnestly clearing his way amid the brambles and thickets of perplexity and error. I am sure there will be many errors in this work and there certainly have been perplexities. But it is now done.

This book is dedicated, as well it should be, to my children, with whom The Rough Wooings has been for a long time as well. For one thing, the names of both my parents (Ruth and Paul) are enshrined in some of theirs. My researches into this topic began in 1962 and finally bore fruit as a PhD (discussed below) in December 1974, after which my family held a party. Wife, every in-law, the lot: it was a lovely occasion. In September 1975, Kate was born and ever since then has (along with first Hannah and then Nat) nagged me to complete this thing. Our penultimate phone call, before Kate received her Bachelor of Surgery in July 1999, contained the words: Dad: the book. And so this is a work not only about families, but also done by a family. My childrens mother actually once just sent the manuscript off to the publisher and told everyone it was done, a plot I aborted. But Pip also gave me one of my best jokes. Seeing on my Amstrad the heading THE ROUEN FETE, she wrote, Cheap shoes ruin feet. It still makes me giggle. And so my thanks to her for that as well for her patience and kindness over the decades.

But all books have many begetters. Mine, having taken this long to appear, has a host. All of the Heads of Department at Lancaster have been uniformly supportive and they should be recognised: Austin Woolrych (who appointed me in 1964), Harold Perkin, Joe Shennan, Martin Blinkhorn, John Gooch (who got me promoted to Senior Lecturer), Michael Heale (he was Best Man at my wedding and I sort of was at his: an honour), Ruth Henig, Eric Evans and Steve Constantine. To all of them my warmest thanks and appreciation: Steve, for example, actually ran me out of town to force me to finish it. But all of my departmental colleagues have been uniformly solicitous: when the word leaked out that it was really at the press, e-mails rained in from Illinois, Missouri and Preston.

When I finally handed the text over to John Tuckwell, his wife Val was there, as were Michael Lynch, Pat Dennison and Norman Macdougall, all of whom had urged me to completion. Michael loaned me his house in Drem during the summer of 1997 and free access to his Departmental Library; John constantly gave me extensions and he and Val did an enormous amount of editing and proof-reading; Norman drove down from St. Andrews to East Linton for the party. I owe them a lot, not least Norman, who had recently linked my name to that of Jamie Cameron, whose book on Marys father I admire so much. My friend, Irene Lewis, has helped me see the book to its conclusion in ways too numerous to detail.

Speaking of proof-reading, this book should really be dedicated to one of my ex-students from 197475 and his mother: Jonathan Bailey and Althea Bailey, who both, and separately, went through every page catching my many errors and suggesting enhancements. Dr. Gordon Glanville also went through my PhD in 1974 with meticulous attention. As extra co-authors, mention should be made of Sandy and Alison Grant, who took away Chapter Three and virtually rewrote it. Ralph Gibson did something similar with the French chapters before his death. Michael Heale and Harry Hanham read through the entirety of the manuscript and gave hearty encouragement. Michael Mullett applied his justly famous generosity and fearsome close eye to going through the page proofs of the entire text and thereby saved me from a host of embarrassments. To him, his wife and his sons I owe great thanks. All of their painstaking efforts have meant that this is a much better work than otherwise it would have been. Dr. Elizabeth Vinestock went through my rather too casual French translations and felicitised them handsomely. Ralph Gibson originally promised to do so, but his illness intervened; one of his last acts was to invite me to speak at his last organised conference: a great honour. Bob Bliss laboured painfully and fruitfully to enhance my chapters on propaganda and the wars.

Gervase Phillips also closely proof-read every page (even to the extent of discovering missing full stops buried deep in the footnotes) and he has saved me from numerous bungles. Even more kindly, he loaned me a copy of the text for his as then not published book, The Anglo-Scots Wars, 15131550: A Military History (Woodbridge, 1999) which proved a Godsend. As my Head of Department averred, That is what one calls superior academic collegiality. I could not agree more. Speaking of battles, I owe a great deal to the insights of James Bell of Longtown who allowed me access to his work on Solway Moss. David Caldwell has taught me everything a man could wish to know about both Pinkie and Eyemouth. Gordon Ewart and Geoffrey Stell have also been generous with their advice and insights.

Given the money and the time, writing books is not that difficult. Without either, I would have become a railroad station agent. So, I really must thank Sir Charles Carter who appointed me as a Temporary Assistant Lecturer when Lancaster opened in 1964. He then made it a permanent appointment. I owe him and his worthy successors not just a remarkably supportive community, but also that monthly pay cheque. I am also deeply indebted to others who have paid actual funds in support of my researches: The British Academy, The 27 Foundation of the University of London, The Cassell Trust, The Institute of Historical Research which granted me a years Fellowship in 196566 and Lancaster Universitys Research Fund. My Universitys policy on study leave has been both enlightened and generously allowed to me, for which I owe it and my colleagues a great debt.

Next page