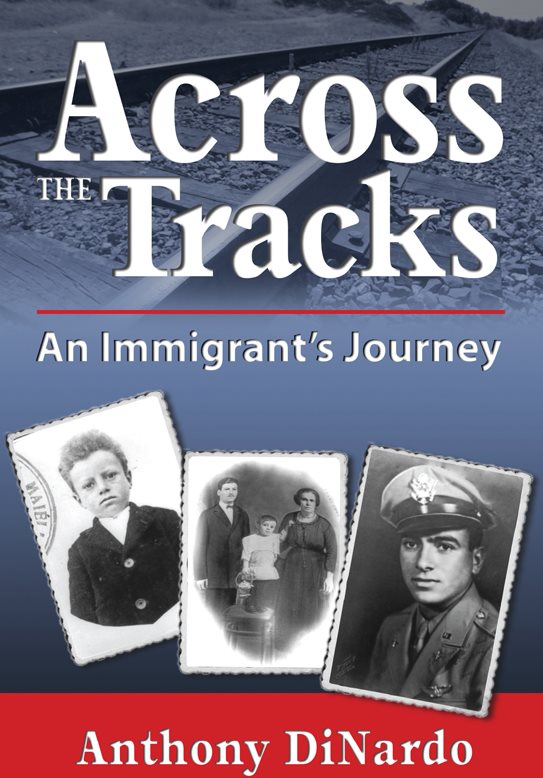

2014 Anthony DiNardo

All rights reserved.

Ebook ISBN 13: 978-1-937721-21-3

ISBN: 9781937721206

LCCN: 2014908077

Published by:

Peter E. Randall Publisher

Box 4726

Portsmouth, NH 03802

www.perpublisher.com

Design by Grace Peirce (nhmuse.com)

Preface

Dear Reader

I am a legal immigrant who has lived in the United States for almost ninety years. During that time, I have witnessed our countrys transformation from a debt-free, world-recognized success that was proudly supported by a loyal citizenry, to todays irresolute debtor facing a multitude of problems. These include wars abroad, a depressed economy, and the enigma of dealing with millions of illegal immigrants crossing uncontrolled borders. As a result, more and more Americans are questioning the competence of our leadership, and significant numbers of them are shedding their burdens of self-responsibility and demanding that government provide for their personal needs, which they term rights and entitlements.

Four generations of Americans have existed over the past century. The so-called Greatest Generation, of which I am a part, grew up in the Great Depression of 1929 through World War II. In that era, the concerns of everyday life dealt mainly with survival, and all family members had to play an active part in meeting household requirements. As their day of graduation from high school approached, teenagers instinctively assumed responsibility for dealing with their own futures. Because the option of college was financially available only to a small percentage of them, the majority sought entry-level jobs in local shops, offices and industry. A relatively few married. But whether decisions were made by choice or chance, everyone understood that the consequences were theirs to bear.

After WWII, the accelerating accomplishments of science and technology were passed on from generation to generation, markedly improving living conditions along the way. At the same time, many changes came about in our human society. One was caused by the strong, persistent argument that young children were to be allowed to behave as they pleased and not as they should. There were also many complaints about the difficulty of public education, which resulted in our nations schools lowering grade requirements for subjects like reading, writing, arithmetic and history.

Along with the easing of burdens on students was a reduction in the amount of time required for them to cope with obligatory home responsibilities. They also found they had more time available for pursuing pleasurable activities. These factors combined to produce a current youthful generation of Americans that bears little resemblance to those of the Great Depression. The outcome is clearly reflected in questions raised daily by more and more Americans: Where is the nation we knew and loved. Why are todays young people so different? What does the future hold for my children and grandchildren?

I have lived through the Great Depression, WWII and subsequent American conflicts. Yet I find myself astounded by the present condition of our beloved nation. Like so many others, I am very disturbed about our global, political and economic crisesand repulsed deeply at the thought of passing on to our children and grandchildren a debt of trillions of dollars. I am most amazed that an absolute improbability has taken place in only four generations: the changing and deterioration of our beloved and powerful America. Beyond that, I believe that yet another hazard existstotally unobserved by most of usthat could bring about the loss our democratic form of government.

While I believe the issues we face deserve addressing in my memoirs, I also realize memoirs are at the mercy of selective memory. Our brain seeks and filters, and the finally written words are the end result of a subjective process. But I will endeavor to record my life honestly, from the viewpoint of both a practitioner and ringside witness.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I thank my wife and loving partner, Elly, who was at my side from the first germ of the idea. Without her constant support and inspiration, there would have been no book.

I thank my devoted and inexhaustible editor, Susan McCool, who gleaned the true meaning of my writings and applied insightful enhancement to every aspect of the book.

My everlasting gratitude to Jan and Joe McCarron and their family: Heather, Dave, and Mike, for their contributions to the characterization, plot and behavioral subtleties of the story.

Thanks to all my other family members for their encouragement: Donna and Kristin; Mark, Diane, Lauren and Rachele; Nan, Stephen, Kait, Steve and Tori; and our inimitable Mia.

Also, thanks to the many friends, too numerous to list, who inspired me with confidence.

Finally, but certainly not last, thanks to Dr. Percival Hunt, professor emeritus of English at the University of Pittsburgh, whose legacy to us post-WWII students was: To strive to say, exactly right, something worth saying.

Part One

Beginnings

Chapter 1

I T WAS A VERY HOT SUMMER when I first started typing these memoirs, and the news in America was filled with reports of the worst electrical blackout in United States history. Millions of people in the Northeast, Midwest and neighboring Canada suffered from heat and total blackness for nearly two days. Stifling weather was also an ongoing problem for our armed forces in Iraq, struggling to eradicate the last vestiges of Saddam Husseins tyranny. But my thoughts were also with my second cousin, Isa; in Abruzzo, Italy; dealing with the hottest summer in recorded European history. Her emails told me she was seeking refuge with her young children, Alessia and Stefano, in the cooler mountain air of the Apennine village of SantEufemia a Maiella. I was born in that village, at the center of the Maiella National Park, almost directly east of Rome. The Maiella, or Mother Mountain, as it is called by the people of the Abruzzo Region, is not a single mountain, but a massifa huge, wild section of the 600-mile Apennine chain that runs the full length of the Italian Peninsula. The park covers 35,000 acres in three provinces: Chieti, Pescara and LAquila. It includes 60 peaks, 30 of which are over 6,000 feet in altitude. Its eastern slopes descend to the nearby Adriatic, while the western slopes devolve into a plain stretching almost one hundred miles to the Mediterranean coast. At an altitude of 2,700 feet, SantEufemia is the highest village on the slope of the Maiella, near the juncture with a sister mountain, Morrone, to create the Passo San Leonardo.

The recorded history of my village goes back to ancient times: in 1064 it was the property of Count Berardo until he gave it to the Abbey of San Clemente a Casauria; in 1145 it passed to Bohemond, Count of Manoppello; in 1301 it went first to the Ughelli family, then on to Giacomo Arcucci, Count of Minervino. When he died, in 1389, the village passed to the DAquino family. Over the last thousand years it underwent several name changes: first Santa Femi, then as Sant Fumia. After the 1861 unification of Italy by Giuseppe Garibaldi, it was granted its present name by special decree of King Vittorio Emmanuel II in 1862.

I have always been in awe of the courage it must have taken for the first SantEufemia pioneer, Francesco Di Giovine, to leave his village and journey for over twenty days to reach an America he knew little or nothing about. He was part of the exodus of eastern and southern Europeans who sought to work in Americas expanding steel mills, railroads and mines owned by such magnates as Andrew Carnegie. He and a few hardy villagers were the first to depart in the late 1870s, to be followed by others after World War I. It was during that war to end wars that many young and healthy village males were conscripted and ordered down the mountain to the city of Sulmona to board trains that took them off to military service. Those who came home from that war, after seeing the world that existed beyond their hamlet and reading letters from earlier pioneers about gold-paved streets in America, chose to strike out on their own. They broke the chain of family ties, a bond close to the heart of Italians, because there was no decent livelihood to be earned at home and, having had little schooling themselves, they felt obligated to provide their children with an education and thus a better chance in life.

Next page