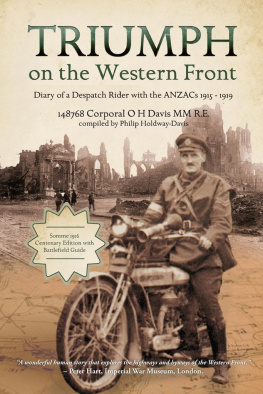

TRIUMPH ON THE WESTERN FRONT

TRIUMPH

on the Western Front

Diary of a Despatch Rider with the ANZACs

19151919

Oswald Harcourt Davis MM R.E.

compiled by Philip Holdway-Davis

Publisher

Insurance Professional Limited (Publishing)

PO Box 6925 Wellesley Street

Auckland City

Auckland 1141

NEW ZEALAND

Phone: +64 (0) 27 380 0127

www.triumphonthewesternfront.com

First edited by FireStep Press in England. Final edit and first published in New Zealand by Insurance Professional Limited.

2016 Philip Holdway-Davis

All rights reserved. Apart from any use under NZ copyright law no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of Insurance Professional Limited or Philip Holdway-Davis.

ISBN 978-0-473-38683-2

Front Cover Image: Soldiers walk among the ruins of bombed buildings in Ypres, Belgium, 1917.

Royal New Zealand Returned and Services Association: New Zealand official negatives, World War 1914-1918. Ref: 1/2-012950-G.

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22789648

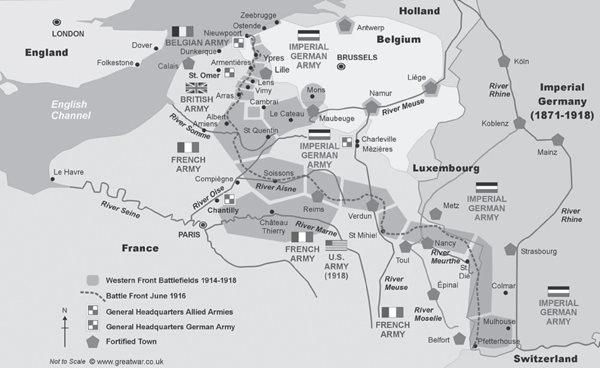

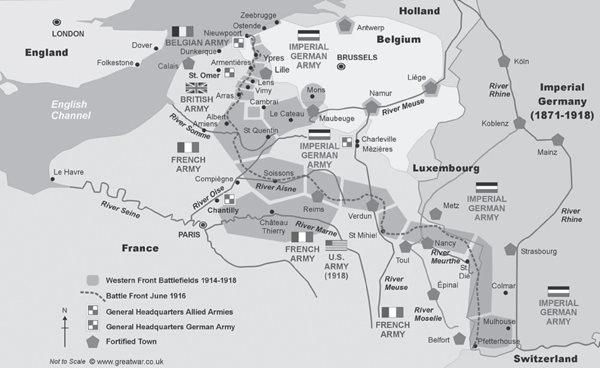

Colour map used with the permission of www.greatwar.co.uk

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

When I read Oswald Daviss diary in the Imperial War Museum I was impressed by two things: the value of his account and the difficulty of reading it on microfilm. It really was hard work.

Yet its value quickly was evident. Oswald was a writer, and an admirer of other writers, a biographer of some in years to come and a published poet in his own right already. I often wished I could have read him with greater ease and at greater leisure.

So to learn that his diary is to be published was a most welcome surprise.

Oswald was a despatch rider, and the importance of the DR in the Great War has been for too long lost sight of. By the time Oswald enlisted, Don R no longer served in the crucial role he had in 1914, but he was still a vital cog in the machinery of war, and Oswalds descriptions of the DRs interaction with the Corps Pigeon Service is, to my knowledge, unique. That fact alone makes this an important book.

But Oswalds account is of much more far-ranging value. He tells us a great deal of what war was like on the Home Front. He delays enlisting out of the honesty and strength of character that marks him and out of loyalty to his familys firm. It seemed best in my deepest self that I should not go at present, but wait until I felt absolutely certain that I ought. In a sense it is difficult not to go. Hard to resist the subtle, strong pressure of public opinion. To yield to this pressure is weakness that was how I decided for the present. When he does go he gives much detail of enlisting and training.

The main attraction of Oswalds account is of course what he tells of despatch riding and the pigeon service, but, as he describes life on the Home Front, he also gives a rich portrayal of everyday life as a soldier, the companionship and exhilaration, the snobbery and degradation: our own humble Tommies were treated as often as not with the most disgusting disdain and humiliating brusqueness by officers with the manners of a railway porter and the brains of a toy dog. The military details that he gives on the Pigeon Service, the travails of the DR he describes, are no less important than the social and military complexities that he explores. Observing field punishment leaves him appalled. He reports the bitterness of an Old Sweat: They can do anything in the army with yer, bar put you in the family way.

Despite some louts and shits he encounters, Oswald enjoys army life: All the soldiers I have seen seem twice as happy and careless as civilians; but soon, in the lives of most of us, great as it is, the war has passed into secondary importance and, as of yore, we are preoccupied by our private affairs. This is natures medicinal way.

Yet never so preoccupied does he become that he is blind to the brutality and ugliness: all the Somme hatefulness mud or dust, Machonocies and bully, sluttish inimical peasants and the strategic dominance of the Hun. Nor is he unaware of how making the best of things can distort recollection: Looking back, the life does not seem unpleasant, and I suppose, with familiarity and confidence and interest in pushing my work to success, the misery of it must have thinned like mist and gradually gained colour and warmth.

A telling side of this observation is that interest in pushing my work to success: Oswalds work ethic is splendid. His home leave he spends in the family business and off his own bat he overhauls the slovenly management he finds in the pigeon service at the Somme. Both here and at Ypres his sense of responsibility is so stern that he is taken advantage of by others, yet while he is aware of this and sometimes resents it he disdains swinging the lead himself. When towards the end he feels the army had almost converted me into a shirker he is rather ashamed. Really he is a sterling example of duty: I like being relied on.

Oswald was a writer and a sensitive soul, in many ways out of place in the rough-and-tumble of army life, yet he stands up for himself when he has to: though Id rather face shells than quarrel with a man, I felt I was right in this case, so he takes on a bully in a boxing ring and beats him and then feels pity for the mans humiliation.

The quality of Oswalds character runs through his account and its his character that gives his diary a good deal of its value. Initially he comes across as a self-conscious, rather Victorian figure, with a good deal of Puritanism seeping through even something of a prig. Here we find a man whom we might not seek out for a night on the town, but who we soon feel certain would guard our confidences. Here is a man to rely on. His honesty can be disconcerting at times. He ponders with distaste: why are young married people so demonstrative? Rather embarrassing for a squeamish chap like myself. But any initially-unattractive prudery is counterbalanced by refreshing, if occasionally alarming, frankness: he is utterly unabashed by his virginal status if anything indignant at the doctor who looked as if he didnt believe me. Anyone who could say all this would hardly dissemble on less personal matters.

The past is a foreign country, L. P. Hartley observes; they do things differently there. There, then, a respectable 33-year-old man might pride himself on his purity (for Oswalds attitude to premarital celibacy was hardly remarkable in that foreign country); today hed be embarrassed by his innocence. Oswald recreates for us this foreign country of the past. As the strength of his character emerges, our trust in his descriptions, his statements, indeed his judgement, is reinforced. His diary is as vivid in its details as it is honest in its reflections on the horror and complexity of war. That both revisionists and anti-revisionists will find much in here to cheer them as well as dismay them is testament to its objectivity and value.

The diary also is as well-written as might be expected of a poet. Much of it is in clipped sentence-fragments, but frequently the lyricist gains the upper hand of the gazetteer: On my way to Shrapnel Corner, ten Gothas steered white and stately, like pieces of pale Gothic masonry loosed from some cathedral roof, each floated, scorning earth against the silver blue of the sky.

That such an original, intelligent, well-written, valuable account could not find a publisher in the 1970s says a great deal about the poisoned attitudes that persisted until recently. For far too long the historiography of the Great War was dominated by the politicised partisan views of AJP Taylor and Basil Liddell Hart and their ilk, and there was a leftist fashion for snigger[ing] at patriotism and physical courage, as George Orwell put it exactly what Oswald Davis and his chums exemplified.

Next page