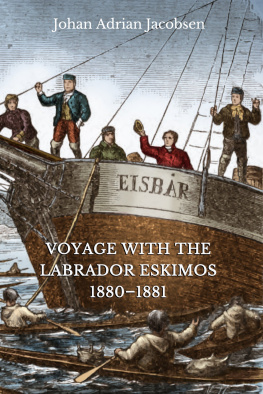

VOYAGE WITH THE

LABRADOR ESKIMOS

18801881

Johan Adrian Jacobsen

VOYAGE WITH THE

LABRADOR ESKIMOS

18801881

Translation of Jacobsens diary (1879-10 to 1880-06-27, 1881-02-21 to 1881-06-25), Jacobsens correspondence, excerpt from Ein Seemansleben, and the ship registration documents. | Dieter Riedel |

Translation of Jacobsens diary (1880-06-28 to 1881-01-20) and excerpt from Eventyrlige Farter. | Hartmut Lutz |

Project editor, coordinator and layout designer | France Rivet |

Cover page: Illustration by M. Hoffmann, published in Beitrge ber leben und treiben der Eskimos in Labrador und Grnland. Berlin, 1880. Colouring by Diane Mongeau.

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada.

Hartmut Lutz, Dieter Riedel and Polar Horizons

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisher, is an infrangement of copyright law.

Legal Deposit, 2019

Bibliothque et Archives nationales du Qubec

Library and Archives Canada

Second edition

ISBN 978-1-7750815-3-1 (paperback), 978-1-7750815-4-8 (epub)

Polar Horizons Inc.

27 De Cotignac Street

Gatineau, Quebec J8T 8E4

info@polarhorizons.com / www.polarhorizons.com/en

To the memory of

Abraham

Maria

Nuggasak

Paingu

Sara

Tigianniak

Tobias

Ulrike

and

Johan Adrian Jacobsen

To all Nunatsiavummiut and

to the descendants of the Jacobsen family.

Table of Contents

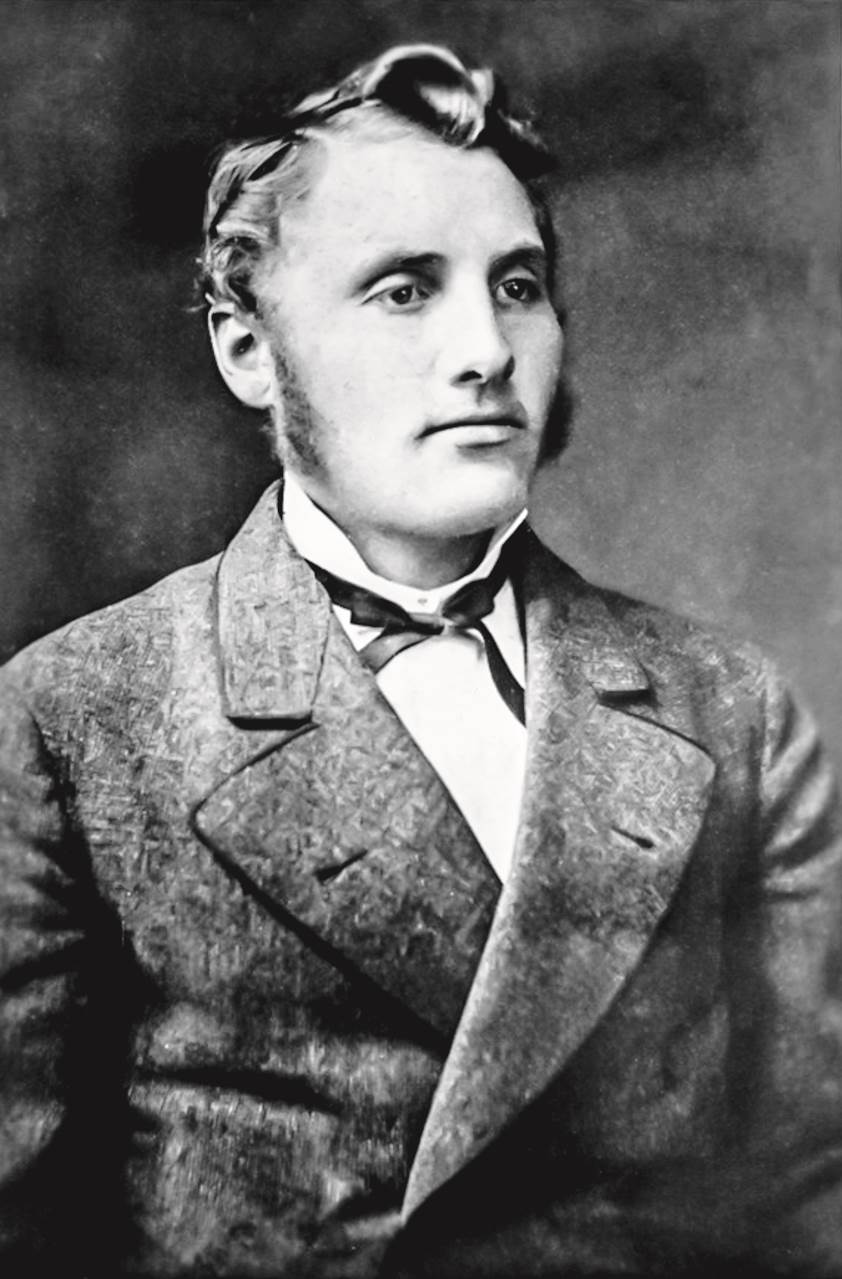

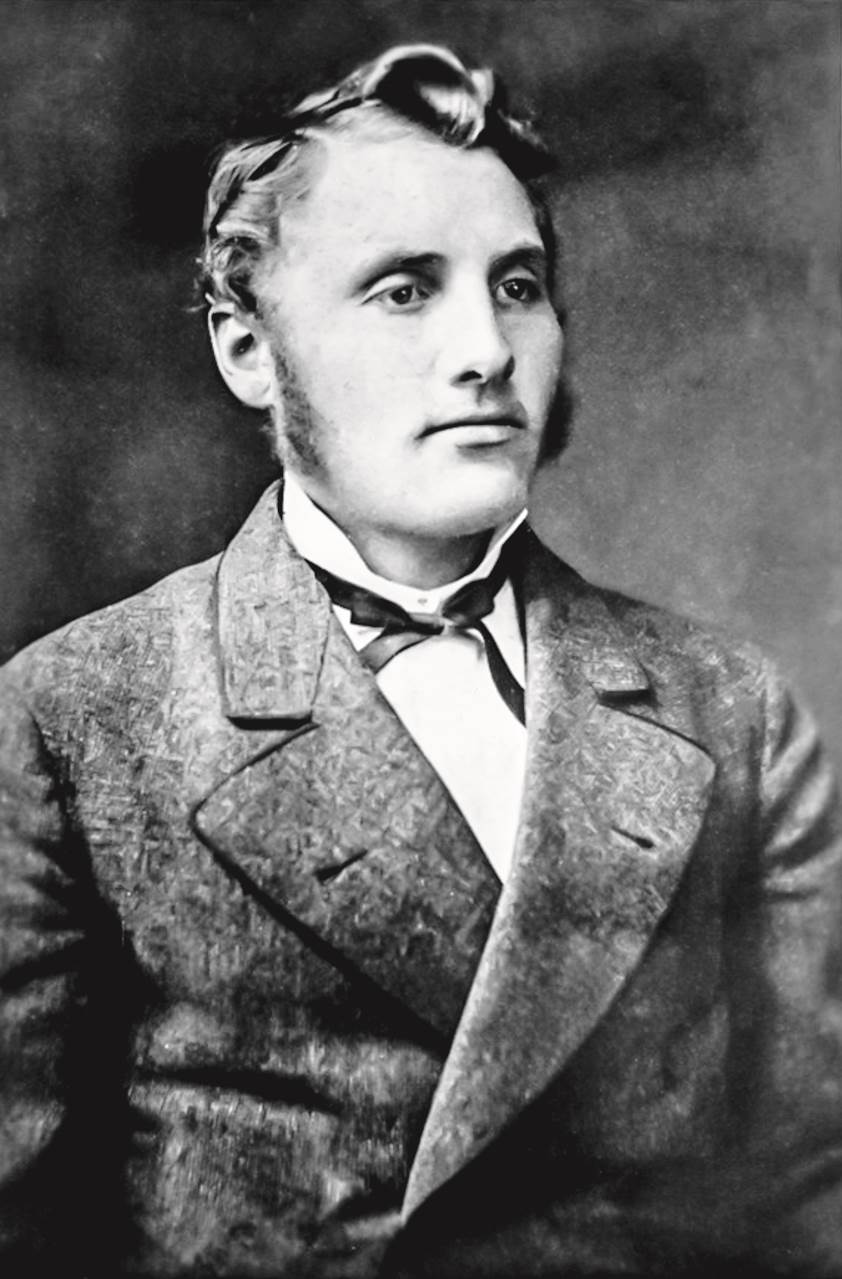

Fig. 1 Johan Adrian Jacobsen. 1881. (Collection of Anne Kirsti Jacobsen)

Foreword

By Cathrine Baglo

Troms Museum Universitetsmuseet

October 2018

As a scholar at Troms University Museum in Northern Norway, researching the live ethnographic exhibitions of Smi and the part Johan Adrian Jacobsen played as Carl Hagenbecks agent, I became acquainted with the heart-wrenching story of the Labrador Inuit in Europe more than fifteen years ago. Since then layers of this story have been revealed, not least through the scrutinizing efforts of France Rivet.

At the outset of my PhD dissertation, it seemed self-evident to understand the live ethnographic exhibitions and the activities of Jacobsen and Hagenbeck as mere acts of the Western worlds denigration and exploitation of indigenous peoples. However, dealing with the research material contemporary newspapers, photographs, contracts, personal accounts and histories kept alive within Smi societies, and not least, Jacobsens diaries and extensive archival documents I realized that they were much more, and that this interpretation, paradoxical as it might seem, often came at the cost of the integrity of the people involved.

The majority of the Smi presenters I identified almost 400 embarked voluntarily on the exhibitions. Most of them welcomed the opportunities they offered. They travelled abroad with clear intentions of communicating information about their culture to foreign audiences. They expressed pride in their traditions, experienced the world, and secured economic means necessary for their survival under colonialism. Some even participated in such exhibitions several times and certain families participated over generations. They often had exceptional experiences and their stories became legendary folklore within their own communities. Frequently they also gave rise to a particular status. Such was the case of Kujagi (Kujanje), the Inuk Jacobsen recruited in Jakobshavn in Greenland for Hagenbeck in 1877 and whose experiences in Europe were radically different from Abraham Ulrikabs. Kujagi became known as the 'Baron' in Western Greenland due to his stay in Europe and the money he earned there. Kujagi wanted to go back with Jacobsen in 1880, but the Danish colonial official imposed a ban. Kujagi perceived the year in Europe as the happiest of his life.

It was hardly a coincidence that the heyday of the ethnographic exhibitions, from approximately 1875 to 1900/1910, coincided with the palmy days of racial theory and social Darwinism. At a time when it was still unusual for researchers to make field studies, the displays doubled as laboratories for various (physical) anthropological investigations. The story of Jacobsen taking Paingus skullcap after the autopsy and the way the Labrador Inuits remains made it to the Musum national dhistoire naturelle where five of the skeletons were mounted for display, is characteristic of the history of museum collections of the time. Yet, it is not the only story. Indigenous presenters, contemporary public, organizers, and impresarios experienced and perceived these exhibitions in a variety of ways. For some presenters the outcome was terribly tragic, for others not.

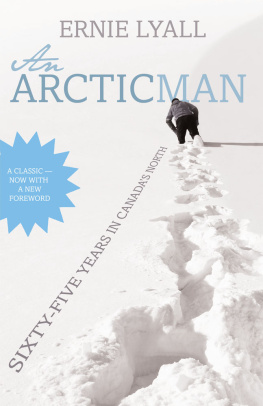

Voyage With the Labrador Eskimos, 18801881 testifies to the complexity and ambiguity of history. The book is based on Johan Adrian Jacobsens account of his experiences with the Inuit he brought from Labrador for Hagenbeck in 1880. Jacobsen was a native of the island of Risya near Troms. After leaving a career as captain of an Arctic hunting and sealing ship, he made a name for himself as a recruiter of indigenous peoples for Hagenbeck. His portfolio also included the collection of artifacts for museums. Jacobsen recruited both Smi from Norway and Sweden, Inuit from Greenland, Sioux from South Dakota, Nuxalk from British Columbia and Inuit from Labrador for Hagenbeck.

Because the live ethnographic exhibitions contributed to stereotypes that still persist, it is important to return to the historical sources to better understand the context of events, actions, and relations that have been lost over time. This will aid a fuller and more complete understanding of this exhibition practice, both from the perspective of the organizers and the indigenous presenters. Voyage With the Labrador Eskimos, 18801881 does precisely that. The book is a translation of Jacobsens diary for the period he spent with the Labrador Inuit and a complement to In the Footsteps of Abraham Ulrikab published by Rivet in 2014.

In this second edition, new sections have been translated, the introduction is expanded and updated with new findings. While Abraham Ulrikabs account of the Inuits experiences in Europe has been translated and published, Jacobsens accounts of his work as an agent for Hagenbeck has never been brought to a larger reading public.

In addition, this second edition includes correspondence between Jacobsen and the Governor of Greenland, from family, friends, and museum employees; as well as documents regarding registration of the ship Eisbr. These documents are brought together without comment allowing the historical sources to speak for themselves. The translation of Jacobsens diary and the added context to what may seem like details, offer new insight into the events that unfolded in Labrador and Europe, and the relations between Jacobsen, Hagenbeck, and the Inuit.

Introduction

By France Rivet

As I sat down to write the introduction to this second edition of Voyage with the Labrador Eskimos, 18801881, I opened Johan Adrian Jacobsens 1880 diary and looked for his August 10, 1880, entry. I wanted to see where exactly he was on that day 138 years ago.

Next page