Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2011 by Randol B. Fletcher

All rights reserved

First published 2011

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.178.0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fletcher, Randol B.

Hidden history of Civil War Oregon / Randol B. Fletcher.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-424-7

1. Oregon--History--Civil War, 1861-1865. 2. Oregon--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Biography. 3. Oregon--History, Local. 4. Oregon--Biography. 5. Portland (Or.)--Biography. 6. United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Campaigns. 7. United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Biography. I. Title.

E526.F55 2011

979.5041--dc23

2011032573

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to my great-great-grandfathers

who served in the War Between the States:

Private John Hays, 25th Indiana Infantry, USA

Private Jeptha Pond, 21st Tennessee Cavalry, CSA

Sergeant Jonathan Pringle, Ballards Company, Arkansas Infantry, CSA

Private Harvey Henderson Shelton, 6th Illinois Cavalry, USA

As we commemorate the 150th anniversary of the American Civil War, it is paramount that we remember the sacrifices of that generation, North and South. There are no longer any Civil War veterans to tell what they did in that war; we must tell their story for them.

Contents

Guarding the Homefront

Oregon Civil War Regiments

Hurrah for Jeff Davis and damn the man that wont! Phillip Mulkey paraded up and down the streets of Eugene City shouting the praises of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Crowds of Union supporters surrounded Mulkey, yelling back at him, and the scene quickly devolved into chaos bordering on violence. Word was sent to summon the provost guard, and troops from the 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry double-timed downtown and placed Mulkey under arrest. As the soldiers were leading Mulkey away, someone handed the unrepentant Rebel a glass of water, and Mulkey defiantly raised the glass and drank a toast to Davis. Thus began the so-called Long Tom Rebellion, a little-known chapter in the hidden history of Civil War Oregon.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the whole of the Federal army numbered barely ten thousand men. Most of the soldiers were stationed at remote forts in the West, and Oregon had a fair amount of those troops. The 4th U.S. Infantry was based at Fort Vancouver and had small posts throughout Oregon and Washington Territories. Ulysses S. Grant was stationed in Oregon Territory briefly in 1852. Future Union general Philip Sheridan had a much longer tenure serving as a junior officer in Oregon from 1855 to 1861. Years after the Civil War, both Grant and Sheridan made triumphant tours of Oregon. The cities of Grants Pass and Sheridan are named in their honor.

When the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln called for volunteers, and each state was given a quota of troops it was expected to provide. Tiny Oregon proved to be problematic for the Lincoln administration. Although Oregon was a free state and had voted for Lincoln in the election, its governor was a proslavery Democrat known as Honest John Whiteaker, and he was not keen on sending Oregon boys three thousand miles away to fight against his political kin. Lincoln pulled the regulars from Oregon and sent them to the front, which left the states small white population living in fear of reprisals from the suppressed native people.

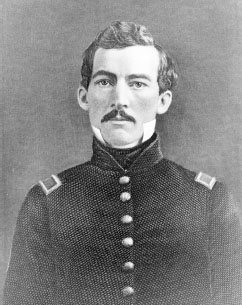

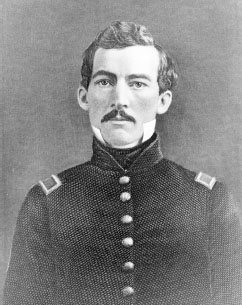

Before achieving fame as a Civil War general, Phil Sheridan served six years as a junior officer in Oregon. Library of Congress.

HORSE SOLDIERS

The army replaced the regulars with volunteer soldiers from California. Then, as now, Oregonians resented California influence. After gaining assurances that local troops would remain in the Northwest, Governor Whiteaker commissioned state senator Thomas Cornelius a colonel and ordered him to raise ten companies of cavalry. Cornelius, a veteran of the Cayuse War, was a Republican from Missouri, so he appealed to both the northern and southern factions within the state. After the war, Cornelius became president of the Oregon Senate and later built Cornelius Pass Road. He ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1886. The town of Cornelius, Oregon, is named in his honor, and he is buried in the Methodist Church Cemetery there.

The Oregon cavalry was assigned to escort immigrants on the Oregon Trail and protect miners in eastern Oregon. They fought a number of skirmishes with bands of indigenous people but suffered just ten battle deaths, including one Native American scout from the Warm Springs tribe. The men of the Oregon cavalry were well paid for their time. While privates in the army drew $13 per month, Oregon cavalry troopers received an additional $100 bounty and 160 acres of land at the end of three years service. Despite above-average pay, Oregon soldiers were susceptible to gold fever. A gold strike in eastern Oregon in 1862 led to ten thousand mining claims being filed that year. Desertion became a major problem as soldiers sent to guard the miners snuck out of camp to try their luck in the gold fields. Nearly 150 men of the Oregon regiments were charged with desertion.

When the fortune-hunting deserters were caught, punishment varied from having their heads shaved to six months of hard labor chained to twelve-pound balls. A few repeat offenders received the ultimate sentence for wartime desertion: death by firing squad. In all but one case, the executions were stayed and the condemned men were pardoned.

The unlucky soldier was a twenty-four-year-old Irishman who had enlisted in the 1st Oregon Cavalry in Jacksonville. Private Francis Ely not only deserted his regiment, but he also took his government-issued mount with him. He was caught on the road to the gold fields and taken to Fort Walla Walla to face court-martial. Convicted of desertion and as a horse thief, he was sentenced to death. On the day set for Elys execution, his captain was so certain that a reprieve would be issued that he posted sentries along the road every twelve miles so that any arriving courier could be rushed to the fort. No message of mercy arrived, and at two oclock in the afternoon of March 6, 1864, Ely was seated on his coffin in the back of a wagon and driven to the place of execution. The Irishman was stood against a high wooden fence, and a black hood was drawn over his head. A firing squad blasted a volley of four musket balls into his chest. One year later, President Lincoln granted amnesty to all army deserters. Ely is buried in an unmarked grave in the Fort Walla Walla Military Cemetery. He was the only soldier on the Pacific coast put to death by the military in the Civil War.

Next page